4.1 The Changing States of Water

Changing States of Water

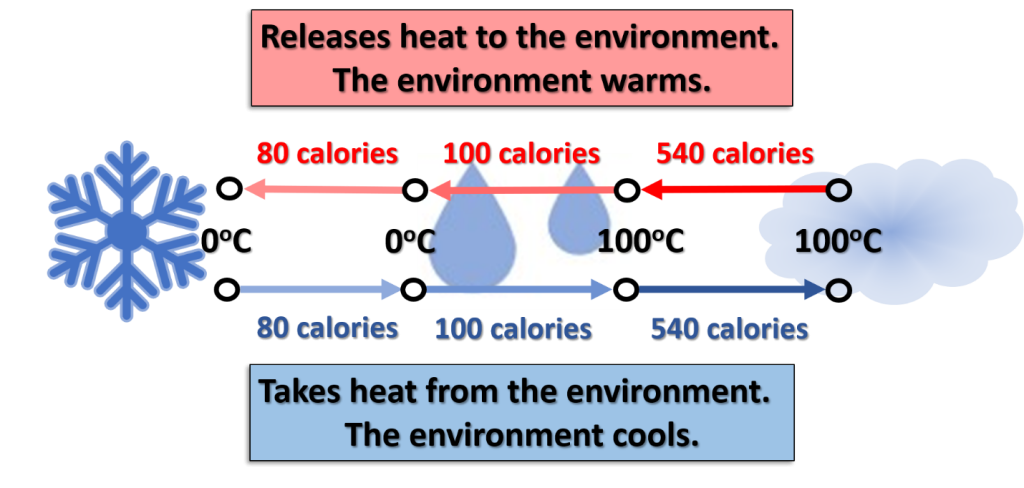

Water is an essential atmospheric element in transferring heat, determining the stability, and creating active weather. We briefly examined the states of water associated with latent and sensible heat in Module 2. Due to the importance of water, the changes associated with its state are reviewed and expanded in this section.

4.1.1 Evaporation, Condensation, and Saturation

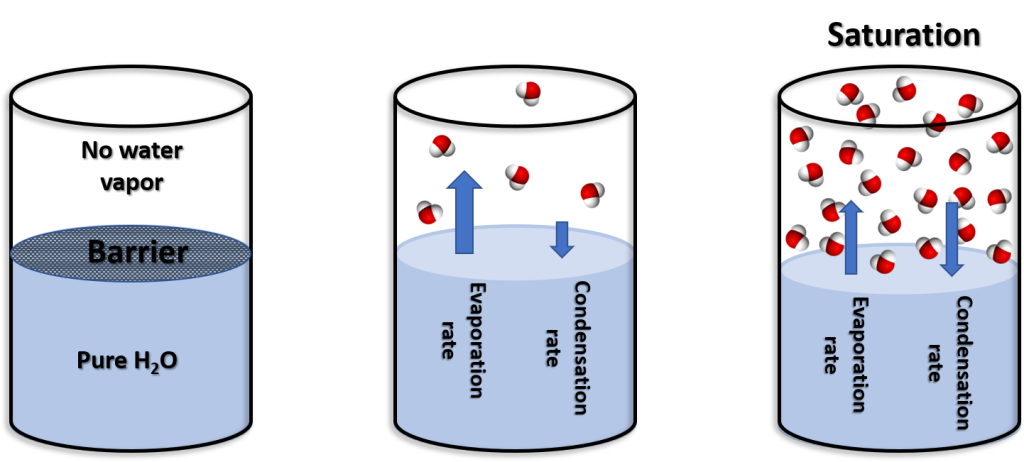

To examine the properties of water (liquid) and water vapor (gas), as an experiment we can fill half a container with water. A barrier is placed between the water the remaining space in the container. All of the water vapor molecules are removed from the “empty” portion of the container. The experiment begins by removing the barrier between the two sections of the container.

Water molecules leave the liquid and become airborne (water vapor) which is called evaporation. The rate of molecules leaving the liquid is the evaporation rate. Likewise, water molecules can again become liquid which is called condensation. Initially, the evaporation exceeds the condensation rate. Eventually, an equilibrium is reached where the evaporation and condensation rates are the same. This equilibrium between the two rates is called saturation.

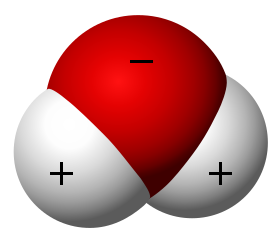

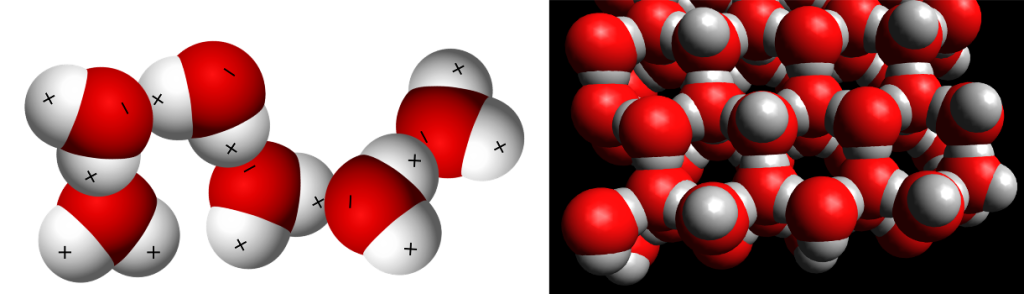

Saturation, evaporation rate, and condensation rate are related to the kinetic energy of the water molecules. Temperature is a measure of this kinetic energy. Water vapor (gas) has the highest kinetic energy and has the highest temperatures. Like any gas, water vapor is compressible. At the molecular level, water consists of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. The hydrogen atoms have a positive charge while the oxygen has a negative charge.

These charges determine the structure of water as it undergoes changes in state. Water vapor as a gas consists of individual molecules mixed in with the other atmospheric gases. Water as a liquid has the molecules aligned with positive and negative charges adjacent to each other. The liquid form is very compact and water is densest at 4oC or 39oF.

Water as a solid (ice) has a six-sided crystalline structure. This structure requires more space as the hydrogen and oxygen molecules align themselves into “fixed” locations. Hence, the reason that water pipes burst when frozen. The density of ice is less than the density of water. Hence, the reason ice cubes float in a cold drink. Water is the only substance on our planet that naturally exists in all three states. This illustration depicts water when frozen as ice.

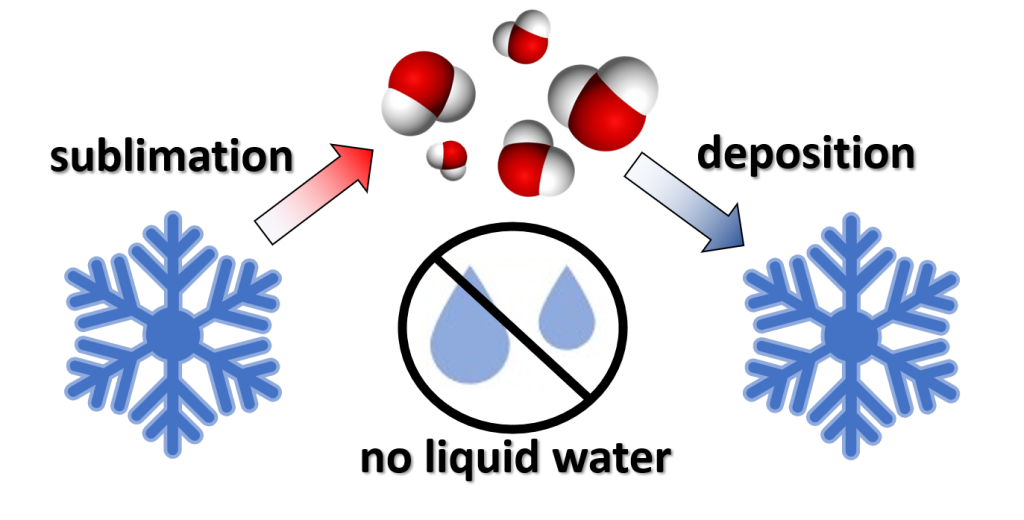

4.1.2 Sublimation and Deposition

The orderly change of state for water is to go from ice to liquid to vapor and vice versa. However, once a water molecule has enough energy it can skip this sequence of steps. The phase change of water going directly from ice to water vapor is called sublimation. Deposition is going straight from water vapor to ice. Deposition is a crucial step in creating precipitation which will be examined later in this course.