Proofreading

Patricia Lynne

When I ask students about their proofreading strategies, they frequently tell me that they read over the paper before they hand it in. When I ask them how well that has worked for them in the past, they shrug. When I ask them to reread something they have handed in a while ago, they get embarrassed and sometimes even mad at themselves because they are seeing errors that they believe they should have caught. The problem, I tell them, is their proofreading strategy, and we get to work trying out alternatives.

In this section, I present a number of proofreading strategies that students have told me work for them. Not all of them work for me; not all of them will work for you. I recommend, though, that you try them, particularly some that you haven’t tried before. You might be able to find more error than you have in the past.

Proofreading vs. Editing

Editing and proofreading require different work, but both require attention to detail. Proofreading is about finding small errors, like typos or missing commas, while editing often involves more substantial work on sentence structure.

However, as I noted in the last section, proofreading and editing are not entirely separate. Be wary, though, of treating them as if they are the same task. If you start proofreading, but switch to editing a few rough sentences, be sure that you switch back to proofreading mode so that you don’t miss the typos!

Hearing the Text: Strategies for Good Ears

Some people can hear problems in their writing much more easily than they can see them, so these variations all rely on you being able to hear what you have written. The strategies below tend to work better when you are able to make marks on a hard copy of your paper, so I recommend that you print your paper out, no matter which you try.

- If you are good at reading out loud exactly what you have written—mistakes and all—you can try reading out loud to yourself. Make corrections as you go, or leave marks (highlighting, underlines, circles) to make corrections later.

- You can ask a friend to read your text out loud to you. This will work best with someone who hasn’t worked with you on other revisions, so they don’t know in advance what you mean. This time, you want to mark places where your reader stumbles or has to back up to read a sentence, as well as places where one or the other of you sees errors. This strategy often works best with two hard copies, one for you and one for your partner.

- You can have your computer read the text out loud to you (see “Tech Talk,” below). Keep in mind that a computer won’t stumble or back up. It also won’t stop until you tell it to. You’ll need to be ready to use some quick-marking techniques if you use this strategy.

Most word-processing software and operating systems have methods for turning text into speech. Microsoft Word® has a “Read Aloud” feature on the Review tab. Google Docs™ has an option to turn on speech under “Accessibility Options” in the Tools menu. Windows® includes a “Narrator” feature in the Ease of Access tools. Apple® computers include a speech option in the Accessibility section of the System Preferences menu.

By the time you read this, however, these options may have changed, and specific instructions may vary for the version of software and/or browser that you are using.

If you’d like to try computer reading and these instructions don’t work, search online for specific instructions for your system and software.

Seeing the Text: Strategies for Good Eyes

Some people see error better than they can hear it. However, finding error this way works better when we change the way the text looks. You can then proofread using your screen or a hard copy, whichever works better for you.

- Change the size or typeface of the font you are using. Changing font types and sizes changes where the beginnings and endings of lines appear, which means that you’re more likely to see errors.

- Most word processors default to using a sans serif font; try a serif font or a different typeface.

- Make the entire text 18-point or even larger.

- Shrink your window size so that you can only see a few lines at a time. This can help you focus on the words in those lines instead of the flow of the paragraph.

- Make every sentence into a separate paragraph (see the activity below).

- This approach can work well in conjunction with shrinking your window size, since each sentence will be separated from the ones around it.

- For an added bonus, this approach can also help you see when you have sentences that begin the same way or too many sentences of the same length in a row.

- It can also help you find dropped quotations.

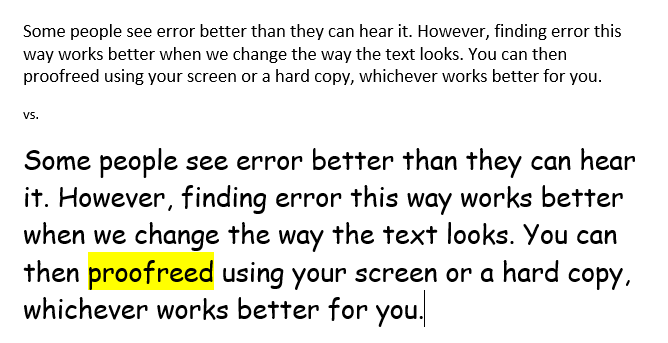

Example: Changing Font Size

Compare these two versions:

The first sample was done in Calibri, the default font in Microsoft Word®, though I made the point size 14 so that it would be a little more readable.

The first sample was done in Calibri, the default font in Microsoft Word®, though I made the point size 14 so that it would be a little more readable.

In the second sample, you can better see errors. I changed the size font to 20, as well as set the font to Comic Sans to better read the work. As you can see, you can better see I mistyped “proofread” and I’m now able to fix that.

Serif vs. Sans Serif

Serif fonts have little decorative strokes on the letters. Examples of serif fonts include Times New Roman, Palatino, and Garamond. These fonts tend to work better in print than on screen for most readers.

Sans Serif fonts have no such decorations. Examples of sans serif fonts include Arial (the default font for Google Docs™) and Calibri (the default font for Microsoft Word®).

First, a few cautions:

- As of this writing, this doesn’t work in Google Docs, so the instructions below are for Microsoft Word only. If you are using Word on a Mac, you will need to use the Advanced Find and Replace.

- Follow these instructions carefully. If you misplace or forget a period, it can be hard to put your paper back in essay format. Some students opt to do this on a copy of their paper, using the spaced-out version to make notes about changes, but making the changes on the original version.

- If you are doing this on the original copy of your paper, be sure to double-check it after you have completed your revisions and converted your paper back to essay format. You want to be sure that your paragraphs are all as they should be.

- Do not try to fix your Works Cited or References list with this technique. This process makes a mess of that list.

Step 1: Convert Your Paper

Open your paper in Word, and take the following steps:

- Click on the “Replace” button on the right side of the Home tab.

- In the dialog box that opens, type the following:

- In the “Find what” blank: Type a period and a space.

- In the “Replace with” blank: Type a period, a caret (Shift-6), the letter “p”, another caret (Shift-6), and another letter “p.”

Note: If you have trouble with the ^p^p part, choose “More” (which becomes “Less” when you click on it) and then “Special” and then “Paragraph Mark” twice. Make sure your cursor is in the “Replace with” blank before you click on the “Paragraph Mark.”

- Click “Replace All.”

Step 2: Edit and Proofread

Using this version, do your editing and proofreading work. Be careful as you edit. Try not to add periods or spaces between sentences, which can also make returning your paper to essay format more difficult.

Step 3: Put Your Paper Back in Regular Format

Assuming you are doing your edits on the same copy you intend to use, you can put it back in regular paragraph form. You just need to reverse the search:

- Click on the “Replace” button on the right side of the Home tab.

- In the dialog box that opens, type the following:

- “Find what:” Type a period, a caret (Shift-6), the letter “p”, another caret (Shift-6), and another letter “p.”

- “Replace with:” Type a period and a space.

Again: If you have trouble with the ^p^p part, choose “More” (which becomes “Less” when you click on it) and then “Special” and then “Paragraph Mark” twice. Make sure your cursor is in the “Find what:” blank before you click on the “Paragraph Mark.”

- Click “Replace All.” Once your paper is back in essay format, double-check to make sure that all of your paragraphs return to the way you want them.

Moving: Strategies for Kinesthetic Writers

Some people think better when they are moving around or when they are moving things around. If this describes you, try these strategies.

- Pace. Get a clipboard, print out your paper, and walk around while you read. Make notes or marks for later changes as you go.

- Print out your paper and cut it up so that you only have one paragraph to work with at a time. Tape together paragraphs that bridge pages. Then pick a paragraph, and start marking it up. For some added benefit, choose paragraphs at random so that the ideas are always moving around, too.

Checking Details

Sometimes, we know where the trouble spots are. We know that we have particular problems with commas or an author’s name or there/their/they’re. It can be helpful to create a checklist for yourself of specific things to look for. For many of these, you can leverage your word processor’s search function to locate the problem spots more efficiently.

Here are some common trouble spots.

Author’s names

Some authors have names that show up as misspellings, so it’s easy to skip over those red squiggles in your word processor. One trick is to add the correct spelling to your word processor’s dictionary so that it will only mark the ones that are truly misspelled.

Commas

Commas are a confusing mark of punctuation for many people, and comma splices are one of the most common errors for early college writers.

If you struggle with commas, first, become familiar with the most important comma rules. Tons of sites online have this information; don’t worry about the number of rules they list, just choose a reputable one like the Purdue OWL or other university website. Then, you can search for commas and carefully proofread to make sure that the ones you have are in the correct place. You’ll have to read carefully, though, to add the ones you’re missing. If you aren’t sure, check with a tutor, your professor, or a friend who seems to understand commas well.

Commas splices happen because writers know that the ideas in two independent clauses belong closer together than an “and” can bring them, but they aren’t sure about how to do this grammatically. Here is a comma splice:

“Solar winds are made up of charged particles originating from the Earth’s Sun, these winds can disrupt satellites and power grids.”

When you have a pair of clauses like this, the comma isn’t strong enough to hold these ideas together—or splice them. To fix this error, you can do a number of things:

Join them with a coordinating conjunction.

“Solar winds are made up of charged particles originating from the Earth’s Sun, and these winds can disrupt satellites and power grids.”

This solution doesn’t work particularly well because the “and” makes the two parts feel too separated.

Use subordination to turn one of the clauses into a dependent clause.

“Solar winds, which are charged particles originating from the Earth’s Sun, can disrupt satellites and power grids.”

OR

“Solar winds, which disrupt satellites and power grids, are made up of charged particles originating from the Earth’s Sun. “

This solution is better in this case, but the one you choose would depend on what you want to emphasize.

Turn one of the independent clauses into a phrase, in this case, one that modifies “solar winds.”

“Solar winds, charged particles originating from the Earth’s Sun, can disrupt satellites and power grids.”

OR

“Solar winds, disrupters of satellites and power grids, are made up of charged particles originating from the Earth’s Sun.”

Again, this solution is better, and you would make a choice depending on what you want to emphasize.

Turn the sentences into a simple sentence with a compound verb.

“Solar winds are made up of charged particles originating from the Earth’s Sun and can disrupt satellites and power grids.”

Again, this one is better than the original. Because it depends on coordination, you would be giving equal emphasis to the two parts.

I have provided a handful of solutions here, but there are many more. The point is for you to understand that when you run into a comma splice, you will want to think actively about how to create the emphasis you want in your sentence.

Quotations

Double-check your quotations. Keep in mind that everything inside of quotation marks (with a few minor exceptions) needs to be exactly what is in the original text. Errors in quotations can indicate a kind of carelessness, particularly since these kinds of errors are avoidable. When you are checking your quotations, it is also a good time to check that you have the correct citation information.

Just as there are specific rules for commas, there are specific rules for quotation marks, but these are simpler:

- Periods and commas go inside quotation marks. This is true even if they aren’t part of the original sentence.

- Question marks, semicolons, and all other punctuation marks can go either inside or outside, depending on whether they are part of your sentence or part of the sentence you are quoting. If they are part of your sentence, they go outside. If they are part of the original sentence, they go inside.

- Citations do not belong inside of quotation marks. They are your marks about where the source is located; they are not part of the original.

If you search for quotation marks, you can find these easily.

Key Points: Proofreading

- Do not just “read over” your writing. Choose a proofreading technique that works for you, such as reading aloud, changing the text’s appearance, or moving while you proofread.

- Check for specific details, including the spelling of authors’ names and comma usage. Also check that everything inside of quotation marks is exactly what’s in the original and that you have used punctuation around quotation marks correctly.

Text Attribution

Material in this section was revised with the help of Waldy Baez, Ameir Mahmoud, and Latrell Williams, students in my class during Fall 2022.

Media Attribution

“Good Proofreading Environment” by Waldy Baez, Ameir Mahmoud, and Latrell Williams is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. The original photograph was cropped slightly by Patricia Lynne.

The idea for “Change Text Size” came from work by Waldy Baez, Ameir Mahmoud, and Latrell Williams. The original file would not display correctly, so Patricia Lynne has redone the work. Credit should be given to both the original student contribution and, if copied, to my work, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

1. Understand the Purpose and Argument

- Identify the Thesis:

- Start by identifying the central claim or thesis of the text. What is the author trying to argue or prove?

- Ex: In Brooks' article, the thesis centers around moral decline being the cause of societal issues like loneliness and meanness.

- Analyze the Author’s Purpose:

- Why did the author write this piece? Is the goal to persuade, inform, provoke, or entertain? Understanding the purpose will help students evaluate the effectiveness of the text.

2. Contextualize the Text

- Historical and Cultural Context:

- Consider the time period and societal issues during which the text was written. How does the context influence the content?

- Ex: Brooks' article reflects concerns about modern American society and the breakdown of community.

- Author’s Background:

- What do we know about the author, and how might their perspective, biases, or experiences shape the text? Analyzing David Brooks’ background as a political commentator helps us see how his perspective informs the argument.

3. Analyze the Structure and Organization

- Text Organization:

- Look at how the text is structured. Does it follow a logical progression? Is the argument easy to follow, or is it fragmented? A well-structured argument is key to persuasiveness.

- Ex: Brooks starts by presenting the problem (increased sadness and meanness) and then provides a historical analysis before suggesting solutions. Is this structure effective?

- Sections and Transitions:

- How does the author transition between ideas? Are there clear topic sentences and smooth connections between paragraphs?

4. Examine the Language and Style

- Tone and Voice:

- Identify the tone of the text. Is it formal, conversational, ironic, or passionate? The tone will affect how the audience perceives the message.

- Ex: Brooks uses a reflective and sometimes concerned tone. How does that affect the way readers relate to his argument?

- Language/Word Choice:

- What kind of language does the author use? Is it simple, academic, emotional, or loaded with jargon? Pay attention to any metaphors, analogies, or symbolism that enhance the argument.

- Ex: Brooks uses phrases like "moral formation" and "emotional, relational, and spiritual crisis." How do these choices influence how we interpret the severity of the problem he describes?

5. Evaluate the Use of Evidence

- Types of Evidence:

- Analyze what kind of evidence the author provides (statistics, historical examples, expert testimony, anecdotes). Is the evidence convincing? Why or why not?

- Ex: Brooks uses data (e.g., statistics on depression and loneliness), historical references, and sociological observations. Are these types of evidence are effective for his argument.

- Reliability of Sources:

- Are the sources credible? If the author relies heavily on specific data or studies, do they come from reputable sources?

6. Identify the Rhetorical Appeals (Ethos, Logos, Pathos)

- Ethos (Credibility):

- How does the author establish credibility? Does the writer appear knowledgeable or trustworthy? How does the author’s background play a role in building ethos?

- Logos (Logic and Reasoning):

- Examine the logical structure of the argument. Is it sound, or are there any logical fallacies? Does the author use facts and reason to support their argument effectively?

- Pathos (Emotion):

- How does the author appeal to the reader’s emotions? Does the author use language that aims to evoke a particular feeling or reaction?

7. Consider Biases and Assumptions

- Author Bias:

- Every author writes with a perspective shaped by their experiences and beliefs. Identify any potential biases or assumptions that may influence the argument.

- Ex: Does Brooks have a bias toward traditional values or certain societal structures? How does this shape his argument about the decline of moral education?

- Reader Bias:

- How might the reader’s background or beliefs influence how they interpret the text? Reflect on how your own biases and experiences might affect your reading.

8. Examine Counterarguments

- Acknowledgment of Opposing Views:

- Does the author address potential counterarguments? How does the author handle opposing viewpoints? If the text doesn’t acknowledge other perspectives, is that a weakness?

- Ex: Brooks briefly mentions other causes of societal problems, like social media and economic inequality, but then argues they don’t address the core issue of moral decline. Is this sufficient, or does he downplay important factors?

9. Reflect on Overall Effectiveness

- Is the Argument Convincing?:

- Form an opinion on whether the author’s argument is effective. What aspects of the text work well, and what might be lacking? Does the text achieve its intended purpose?

- Strengths and Weaknesses:

- What are the key strengths of the article? What weaknesses do you identify in terms of logic, evidence? What about in the rhetorical strategies like language, tone, and style?