Revising 2: Revising Paragraphs

Patricia Lynne

While making global revisions, you have probably also worked on revising paragraphs to clarify your point or add more explanation. That work is important, but the strategies in this section are designed to help you make sure that your individual paragraphs are solid by looking at the specific qualities of good paragraphs: focus, development, and coherence. These can be particularly useful for paragraphs that don’t seem to be working well.

Color Coding Topics: A Strategy to Strengthen Focus

A focused paragraph has one main idea that usually appears in a topic sentence (at least in academic writing), and the rest of the paragraph elaborates on that idea. If your paragraph isn’t focused, your reader may struggle to follow your point and the connections among the ideas in your paragraph.

This activity works on body paragraphs, but not really on introductions or conclusions. As with previous activities, you can do this with the highlighter feature in your word processor or with actual highlighters on a printed copy of your paper.

Part 1: Highlighting

- Identify the paragraph’s topic sentence and highlight it in one color.

- Look at the next sentence (or the first sentence in the paragraph if the topic sentence isn’t the first sentence), and decide if it’s on the same topic. If it is, highlight it in the same color. If it isn’t, highlight it in a different color.

- Continue highlighting this way, matching the highlight color to the sentence topic, until all of the sentences in the paragraph are marked. Note that you can have split sentences (sentences that have more than one topic in them). In those cases, highlight the parts of the sentence in different colors accordingly.

Part 2: Analyzing Your Highlighting

- If your paragraph is all one color, then you have a well-focused paragraph.

- If your paragraph contains two colors, it’s probably fine. Paragraphs can shift focus sometimes, so a paragraph that has two colors may still work as a single paragraph. Look carefully at the topics to make sure that they are connected and that you haven’t dropped in a new topic in that really belongs in a different paragraph.

- If your paragraph has three or more colors, you probably need to think about separating the topics.

- I frequently see this problem when the writer starts a paragraph on one idea, realizes that they need to explain a specific point before getting into the original topic, and then shifts back to the first topic, with an additional shift in topic later in the paragraph. Often, that second topic can be pulled out and developed into a new paragraph that is placed before the current one.

- This can also happen when the paragraph is very long and simply isn’t broken into chunks to make reading easier. Look for those moments when the colors shift, which can indicate good places for paragraph breaks. The new paragraphs might also need a little development (see the next strategy).

Example: Color-Coded Paragraphs

Here are some examples of paragraphs with one, two, and three colors.

Example 1

If you look up at the sky, you’ll notice it’s blue during the day. The reason why the sky is the color we see is because of how the light bounces, causing us to see a light blue instead of red. The light blue we see is also very beautiful, and an activity that some people enjoy doing is looking up at the sky.

While the paragraph above is relatively short, every sentence ties in with one another. Of course, the paragraph could use more work, but the paragraph is well focused.

Example 2

If you look up at the sky, you’ll notice it’s blue during the day. A question that children often ask adults is why this is. However, not many people can come up with an answer, even if they’re taught in school. The reason why the sky is the color we see is because of how the light bounces, causing us to see a light blue instead of red. By the time people become adults, they tend to forget how and why this is, causing them to simply state that they don’t know when children ask. The light blue we see is also very beautiful, and an activity that some people enjoy doing is looking up at the sky.

This is an example of a paragraph that shifts focus but sticks with the main point. While this one probably doesn’t need to be broken up (though it could benefit from some reorganization), you can have a paragraph that has two colors where the different sentences shift focus drastically. Such a paragraph would need to be broken up.

Example 3

If you look up at the sky, you’ll notice it’s blue during the day. A question that children often ask adults is why this is. However, not many people can come up with an answer, even if they’re taught in school. But did you know that in California, the sky has sometimes turned orange due to fires? Residents couldn’t even leave their homes, even if the sky looked hauntingly beautiful. The reason why the sky is the color we see is because of how the light bounces, causing us to see a light blue instead of red. By the time people become adults, they tend to forget how and why this is, causing them to simply state that they don’t know when children ask. The light blue we see is also very beautiful, and an activity that some people enjoy doing is looking up at the sky.

While this paragraph has mostly the same focus points as the previous example, look at the blue section. These two sentences would work better as a topic sentence in a new paragraph due to the focus shifting away from the sky being blue to the sky being orange in California.

Occasionally, multiple colors in the same paragraph indicate a larger problem with topic organization throughout the paper. When this happens, the same topics appear in small clumps throughout the paper. One of my former students called these “rainbow paragraphs.”

As you can see in the example below, there’s a glaring issue with the focus of the paragraph. While the yellow and green sentences could work together, the other three colors would work best as their own paragraphs.

If you look up at the sky, you’ll notice it’s blue during the day. A question that children often ask adults is why this is. However, not many people can come up with an answer, even if they’re taught in school. But did you know that in California, the sky has sometimes turned orange due to fires? Residents couldn’t even leave their homes, even if the sky looked hauntingly beautiful. A great way to learn about major fires is the news. Time and again, forest fires in the United States are shown on the news. People who have done gender reveal parties have recently been responsible for fires. These parties tend to involve fireworks or other explosives, and the people handling them don’t think of taking any precautions.

Rainbow paragraphs are really a global-level revision problem rather than a paragraph-level revision problem, and you can find them by doing a more complete version of this focus activity.

If you suspect you have a rainbow paragraph problem, create a key where you color code different topics in your paper, and then highlight according to that key. You can then gather all of the sentences that deal with each topic to work together in one or more paragraphs.

Revisiting the Evidence/Explanation Balance: A Strategy to Strengthen Development

A paragraph that is sufficiently developed has enough evidence and enough explanation, with “enough” being defined mostly by the reader. You can use the same kind of highlighting activity that you did for your entire paper to make sure that you are balancing evidence and explanation at the paragraph level, too. This strategy can help you identify paragraphs with too little evidence or too little explanation.

In the case of too little evidence, you may find that you thought your reader would already understand your point. To you, the point seems obvious, but keep in mind that your reader has not been working with the evidence that you have. Show them the source material that supports your ideas.

In the case of too little explanation, students commonly try to let the evidence speak for itself. Evidence exists out in the world and doesn’t mean anything until we start interpreting and explaining it. You need to provide your reader with some of that explanation.

This activity can help when you have a paragraph that you believe is out of balance.

Part 1: Highlighting

Using the highlighting feature in your word processor or actual highlighters on print versions, do the following:

- Highlight or otherwise mark all the supporting evidence in the your paragraph.

-

- From textual sources, this would include quotations and paraphrases, facts, examples, and background information. Include the attributive tags and citations in these highlights.

- You can also do this with evidence from personal experience and observations or data that you have personally collected. These would be evidence in projects that don’t rely heavily on published sources.

- Using a different color, highlight or otherwise mark differently all of the explanations of that evidence that you have provided. This material should all be coming from your own ideas.

- Be sure that you have highlighted every sentence in the body of your paragraph. Note: You may have sentences that are part evidence and part explanation. That is perfectly fine.

Part 2: Analyzing Your Balance

Your focus here is a bit different from the earlier balancing activity where you examined the balance in your entire paper. Here you are looking for large-ish blocks of one color or the other in a single paragraph, usually three or more sentences. Those blocks are potential problem spots.

- Blocks of evidence can indicate the need for more explanation. While sometimes you will spend the majority of a paragraph providing a summary or an extended example from a source, much more often, you will want to present a little evidence (perhaps a sentence or two) and then explain how that evidence relates to your thesis or your point in that paragraph.

- Blocks of explanation can indicate the need for more evidence. Work through your sentences and determine whether a skeptical reader (one who doesn’t automatically agree with you) would be inclined to ask “How do you know?” If you find any of those moments, look for evidence you can bring in to support your point.

Don’t assume that you need to make a change every time you have one of these blocks, particularly when the blocks are explaining one of your points. Sometimes, these larger blocks are necessary.

Mapping Paragraphs: A Strategy to Strengthen Logical Coherence

A coherent paragraph holds together logically and stylistically; the ideas flow from sentence to sentence so that the reader can understand the author’s line of thought. Stylistic coherence is discussed in the editing section, but logical coherence is a paragraph-level matter.

When a paragraph coheres, it holds together topically—like a focused paragraph does—but its sentences logically lead your reader, step-by-step, through your thinking.

The activity below can pick up problems with focus as well as coherence, so if you don’t have substantial difficulties with focus, this activity might be a better choice for you. Also, unlike the focus activity, this one works on all paragraphs, including introductions and conclusions.

This activity can work well when you have a paragraph that feels jumbled or jumpy. It may be all on the same topic but it still isn’t connecting well from point to point.

This exercise can be done on a computer, but it is probably easier to draw the map on a piece of paper.

Here, I’ll use an example paragraph:

(1) The technology barrier is what humanity will need to work on. (2) Even if we could convince everyone to pay the enormous prices of installation and switch to clean energy, we still would not have the technology to support this substantial change. (3) Nevshehir states that the technology that we have today is still expensive and not powerful enough compared with what fossil fuels deliver. (4) Fossil fuels have one major advantage over renewable resources: Oil-based fuels are stable and predictable. (5) On the other hand, solar and wind electricity production can vary, which can leave people’s homes vulnerable to energy shortages. (6) Moradiya brings another barrier into the technology issue when he states “Although the development of a coal plant requires about $6 per megawatt, it is known that wind and solar power plants also required high investment. In addition to this, storage systems of the generated energy are expensive and represent a challenge in terms of megawatt production.” (7) In these sentences, Moradiya shows that in addition to the costs of installing the power generators (e.g., solar panels and wind turbines), the costs to store excess energy can be a major hurdle, since the technology that we have today makes large batteries that could sustain cities expensive.

Works Cited

Moradiya, Meet A. “The Challenges Renewable Energy Sources Face.” AZoCleantech, 11 Jan. 2019, www.azocleantech.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=836.

Nevshehir, Noel. “These Are the Biggest Hurdles On The Path to Clean Energy.” World Economic Forum, 19 Feb. 2021, www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/02/heres-why-geopolitics-could-hamper-the-energy-transition/.

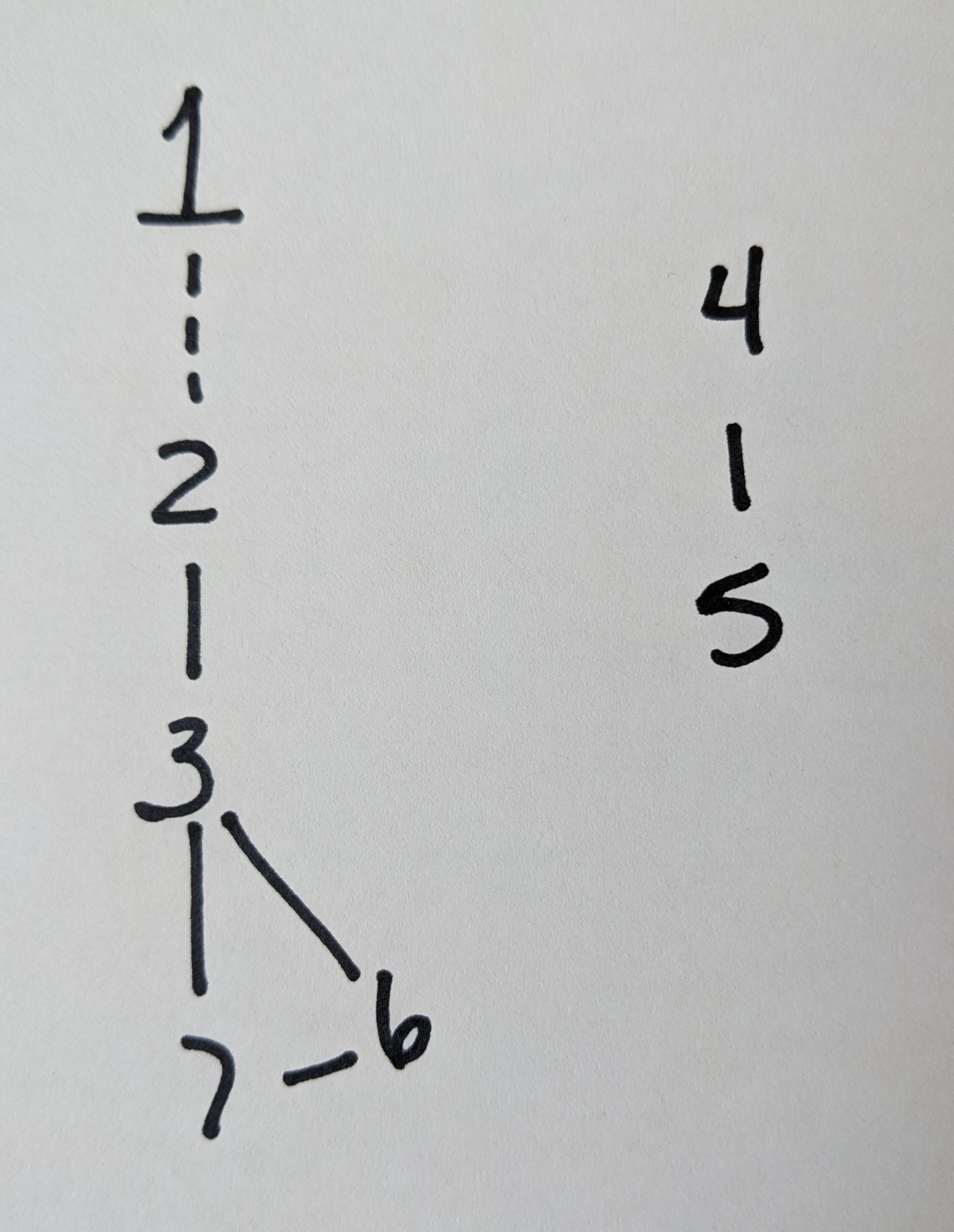

Part 1: Create the Map

- Number all the sentences in your paragraph. Notice that sentences in a quotation are considered all part of one sentence (sentence 6 in the example).

- For each sentence after the first one, draw lines to indicate which sentence that one logically follows from. Looking at the topic of each sentence can help.

-

- Use solid lines to indicate a clear logical connection between sentences.

- Use dashed/dotted lines to indicate a connection that isn’t as clear or strong as it could be.

- It is possible that a sentence may connect to more than one sentence.

- Sentences that are disconnected from all of the others in the paragraph should have no lines.

To the right, you’ll see a map of the paragraph above. In this map, sentence 1 is only loosely connected to 2. Sentences 2 and 3 are solidly connected and sentences 6 and 7 are solidly connected to each other and to sentence 3. Sentences 4 and 5, however, are connected to each other, but not to the rest of the map.

Part 2: Analyze the Map

Once you have created the map, you can use it to identify and correct trouble spots.

- Here are some of the most common problems:

- Sentences that aren’t connected to any others in paragraph (sentences 4 and 5 in the diagram). These usually indicate a sentence or group of sentences that belong in another paragraph. I see this most frequently with transition sentences that appear at the end of a paragraph instead of the beginning of the next. I also see this with ideas that need more explanation, sometimes in a separate paragraph.

- Sentences connected by dashed/dotted lines (sentences 1 and 2 in the diagram). These sentences probably belong together, but the logic between isn’t as clear as it needs to be for the reader to follow. These connections can often be strengthened by adding a little more explanation to one of the two sentences—or sometimes in a sentence between them.

- Sentences whose connection jumps over sentences (sentences 3 and 6 in the diagram, which skip over sentences 4 and 5). Usually, this means that the sentences are out of order. Try moving the sentences so that those that are connected on your map are next to each other. You may have to adjust the wording of the sentences, including transitions, as you do this.

- Not everything in a map is necessarily a problem:

- A single sentence with multiple sentences connected to it (sentence 3 in the diagram). This probably indicates an important sentence for helping your reader understand the relationships among the ideas in your paragraph. Usually, these don’t need any revision—at least not because of this.

- A late sentence that comes back to an early sentence in your paragraph (not seen in this diagram). This is often a way of either wrapping up an explanation and making the connection clear to your reader or starting a new explanation from a key central sentence in the paragraph. Usually, these don’t need any revision.

- Long chains of sentences in the same paragraph (not seen in this diagram). These may be a problem if your paragraph is very long. Look at whether one or more of those chains should be turned into a separate paragraph.

Checking Introductions and Conclusions

Whether we draft our introductions first, last, or somewhere in the middle, we are often at a different place in our thinking when we draft our conclusions. As a result, sometimes the ideas in the two paragraphs don’t align.

Also, sometimes a conclusion sounds more like an introduction. When I ask students to do a mixed-up paragraph exercise, about 20% of the students in any given class end up with the introduction and conclusion switched. This usually happens when the conclusion does too much summary work and not enough gesturing forward.

The following activity can help you identify problems with both paragraphs and check the alignment between the two.

The first part of this activity can be more effective with a partner who knows the assignment but who isn’t familiar with your paper, but you can do this with someone who doesn’t know the assignment, or you can do it for yourself as long as you have given yourself enough time to come back to your paper as a reader.

Part 1: Thesis and Content Work (done by a partner, ideally)

Use the highlighter feature in your word processor or an actual highlighter on paper to do the following (be sure to set up a key to the color-coding):

- Analyze the introduction:

-

- Highlight the sentence you believe is the thesis statement.

- If there is more than one sentence that you believe could be the thesis or that you think need to be together to make the thesis, make a note of the issue.

- Analyze the conclusion:

-

- Highlight/mark the restated thesis in the same color as you did the thesis in the introduction.

- Highlight/mark (in another color) any other sentences that seem to be summarizing the paper.

- Highlight/mark the gesture forward in a third color, and identify which approach you think the author is using in that gesture.

- Make note of any suggestions you have for strengthening the conclusion.

- Make a list of what you expect to see in the paper based just on the introduction and conclusion:

-

- Add a few spaces between the introduction and the conclusion paragraphs.

- In the space you have created, make a list of the topics you expect the author to cover, based on what you see in the introduction and conclusion.

Part 2: Reviewing the Feedback (done by the author)

- Look at the highlighting of the thesis in your introduction. If the identified sentence was not what you thought your thesis was, think about whether and how to revise it so that it is clearer.

- Look at the highlighting of the restated thesis. If the identified sentence was not what you thought your restated thesis was, think about whether and how to revise it so that it is clearer.

- Compare the two statements of the thesis. Are they making essentially the same claim? Are they using distinct phrasing? You want both of these answers to be “yes.”

- Look at any additional summary that was highlighted in the conclusion. Try deleting that summary. Remember that the reader of a college-level paper is expecting a gesture forward, not a recap, unless the paper is long (more than about 2000 words).

- Look at the material marked as your gesture forward. Was this material identified in the way you had intended? If not, what could you do to make it clearer?

- Look at the list of topics that your partner thinks would be covered in this paper. Make note of any that differ from your actual organization. Significant differences could signal a need to return to global revision.

Once you have looked at all of these aspects of the feedback you have received, ask your partner about any of his/her feedback that you don’t understand. Then, write up notes on what, if anything, you are going to change and what you are not going to change based on this feedback.

Checking Paragraph-Level Transitions

During your revision process, you may have moved sentences and paragraphs around to make your meaning clearer. At this point, it is a good idea to check your transition sentences to make sure that they are conveying the logic and connections you want to make.

Remember that transition sentences almost always begin paragraphs, and they should make a gesture backward and a gesture forward so that your reader understands the connections between those paragraphs. While there may be a transition between your introduction and your first body paragraph, transition sentences are more important in later paragraphs, where you should be using them to help your reader see how the ideas in different paragraphs connect.

To make sure that your transition sentences are doing the work you want, do the following for each paragraph after the introduction:

- Identify the transition sentence. Remember that this will almost always be the first sentence of the paragraph.

- Check the gesture backward. Does the sentence give your reader some information that they already know from the previous paragraph(s)? It can sometimes help to highlight this part of the transition sentence to make sure that you can identify it. These parts may include the following:

-

- Repeated words, phrases, or even clauses from the previous paragraph

- Transition words

- Summaries of ideas previously discussed

- A reminder of the thesis of the project or the main point of a section of the paper

- Look at the remainder of the transition sentence. Is it providing some kind of gesture forward or introduction to new information?

Key Points: Revising Paragraphs

- Strong paragraphs are focused, developed, and coherent. There are activities (explained in this chapter) that you can try to help you find weaknesses in these areas.

- Make sure that your introduction and conclusion are aligned and that your conclusion doesn’t waste time summarizing a paper shorter than about 2000 words.

- Check transition sentences by making sure that the first sentence in each paragraph after the introduction includes a reference to ideas already covered and an introduction to new ideas to be explained in the paragraph that includes the transition.

Text Attributions

“Color Coding Topics: A Strategy to Strengthen Focus” was revised with the help of James Bushard, a student in my class during Spring 2022, who also provided the examples, including the example in “Rainbow Paragraphs.”

“Mapping Paragraphs: A Strategy to Strengthen Logical Coherence” was revised with the help of Lorenzo Locks Azeredo, a student in my class during Spring 2022, who also provided the example. The map provided is my recreation of his map.

Because of all their influence, you might worry that research questions are very difficult to develop. Sometimes it can seem that way. But we'll help you get the hang of it and, luckily, none of us has to come up with perfect ones right off. It's more like doing a rough draft and then improving it. That's why we talk about developing research questions instead of just writing them.

Steps for Developing a Research Question

The steps for developing a research question, listed below, can help you organize your thoughts.

Step 1: Pick a topic (or consider the one assigned to you).

Step 2: Write a narrower/smaller topic that is related to the first.

Step 3: List some potential questions that could logically be asked in relation to the narrow topic.

Step 4: Pick the question that you are most interested in.

Step 5: Change the question you’re interested in so that it is more focused and specific.

ACTIVITY: Following the Steps

MOVIE: Developing Research Questions

As you view this short video on how to develop research questions, think about the steps. Which step do you think is easiest? Which do you think is the hardest?

Practice

Once you know the steps and their order, only three skills are involved in developing a research question:

- Imagining narrower topics about a larger one,

- Thinking of questions that stem from a narrow topic, and

- Focusing questions to eliminate their vagueness.

Every time you use these skills, it’s important to evaluate what you have produced—that's just part of the process of turning rough drafts into more finished products.

Maybe you have a topic in mind but aren't sure how to form a research question around it. The trick is to think of a question related to your topic but not answerable with a quick search. Also, try to be specific so that your research question can be fully answered in the final product for your research assignment.

ACTIVITY: Thinking of Questions

For each of the narrow topics below, think of a research question that is logically related to that topic. (Remember that good research questions often, but not always, start with “Why” or “How” because questions that begin that way usually require more analysis.)

Topics:

- U.S. investors’ attitudes about sustainability

- College students’ use of Snapchat

- The character Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird

- Nature-inspired nanotechnologies

- Marital therapy

After you think of each research question, evaluate it by asking whether it is:

- Logically related to the topic

- In question form

- Not answerable with a quick Google search

- Specific, not vague

Sometimes the first draft of a research question is still too broad, which can make your search for sources more challenging. Refining your question to remove vagueness or to target a specific aspect of the topic can help.

ACTIVITY: Focusing Questions

The first draft research questions below are not focused enough. Read them and identify at least one area of vagueness in each. Check your vagueness with what we identified. It’s great if you found more than we did because that can lead to research questions of greater specificity. See the bottom of the page for our answers.

First Drafts of Research Questions:

- Why have most electric car company start-ups failed?

- How do crabapple trees develop buds?

- How has NASA helped America?

- Why do many first-time elections soon after a country overthrows a dictator result in very conservative elected leaders?

- How is music composed and performed mostly by African-Americans connected to African-American history?

ACTIVITY: Developing a Research Question

ANSWER TO ACTIVITY: Focusing Questions

Some answers to the “Focusing Questions” Activity above are:

Question 1: Why have most electric car company start-ups failed?

Vagueness: Which companies are we talking about? Worldwide or in a particular country?

Question 2: How do crabapple trees develop buds?

Vagueness: There are several kinds of crabapples. Should we talk only about one kind? Does it matter where the crabapple tree lives?

Question 3: How has NASA helped America?

Vagueness: NASA has had many projects. Should we should focus on one project they completed? Or projects during a particular time period?

Question 4: Why do many first-time elections soon after a country overthrows a dictator result in very conservative elected leaders?

Vagueness: What time period are we talking about? Many dictators have been overthrown and many countries have been involved. Perhaps we should focus on one country or one dictator or one time period.

Question 5: How is music composed and performed mostly by African-Americans connected to African-American history?

Vagueness: What kinds of music? Any particular performers and composers? When?

Because of all their influence, you might worry that research questions are very difficult to develop. Sometimes it can seem that way. But we'll help you get the hang of it and, luckily, none of us has to come up with perfect ones right off. It's more like doing a rough draft and then improving it. That's why we talk about developing research questions instead of just writing them.

Steps for Developing a Research Question

The steps for developing a research question, listed below, can help you organize your thoughts.

Step 1: Pick a topic (or consider the one assigned to you).

Step 2: Write a narrower/smaller topic that is related to the first.

Step 3: List some potential questions that could logically be asked in relation to the narrow topic.

Step 4: Pick the question that you are most interested in.

Step 5: Change the question you’re interested in so that it is more focused and specific.

ACTIVITY: Following the Steps

MOVIE: Developing Research Questions

As you view this short video on how to develop research questions, think about the steps. Which step do you think is easiest? Which do you think is the hardest?

Practice

Once you know the steps and their order, only three skills are involved in developing a research question:

- Imagining narrower topics about a larger one,

- Thinking of questions that stem from a narrow topic, and

- Focusing questions to eliminate their vagueness.

Every time you use these skills, it’s important to evaluate what you have produced—that's just part of the process of turning rough drafts into more finished products.

Maybe you have a topic in mind but aren't sure how to form a research question around it. The trick is to think of a question related to your topic but not answerable with a quick search. Also, try to be specific so that your research question can be fully answered in the final product for your research assignment.

ACTIVITY: Thinking of Questions

For each of the narrow topics below, think of a research question that is logically related to that topic. (Remember that good research questions often, but not always, start with “Why” or “How” because questions that begin that way usually require more analysis.)

Topics:

- U.S. investors’ attitudes about sustainability

- College students’ use of Snapchat

- The character Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird

- Nature-inspired nanotechnologies

- Marital therapy

After you think of each research question, evaluate it by asking whether it is:

- Logically related to the topic

- In question form

- Not answerable with a quick Google search

- Specific, not vague

Sometimes the first draft of a research question is still too broad, which can make your search for sources more challenging. Refining your question to remove vagueness or to target a specific aspect of the topic can help.

ACTIVITY: Focusing Questions

The first draft research questions below are not focused enough. Read them and identify at least one area of vagueness in each. Check your vagueness with what we identified. It’s great if you found more than we did because that can lead to research questions of greater specificity. See the bottom of the page for our answers.

First Drafts of Research Questions:

- Why have most electric car company start-ups failed?

- How do crabapple trees develop buds?

- How has NASA helped America?

- Why do many first-time elections soon after a country overthrows a dictator result in very conservative elected leaders?

- How is music composed and performed mostly by African-Americans connected to African-American history?

ACTIVITY: Developing a Research Question

ANSWER TO ACTIVITY: Focusing Questions

Some answers to the “Focusing Questions” Activity above are:

Question 1: Why have most electric car company start-ups failed?

Vagueness: Which companies are we talking about? Worldwide or in a particular country?

Question 2: How do crabapple trees develop buds?

Vagueness: There are several kinds of crabapples. Should we talk only about one kind? Does it matter where the crabapple tree lives?

Question 3: How has NASA helped America?

Vagueness: NASA has had many projects. Should we should focus on one project they completed? Or projects during a particular time period?

Question 4: Why do many first-time elections soon after a country overthrows a dictator result in very conservative elected leaders?

Vagueness: What time period are we talking about? Many dictators have been overthrown and many countries have been involved. Perhaps we should focus on one country or one dictator or one time period.

Question 5: How is music composed and performed mostly by African-Americans connected to African-American history?

Vagueness: What kinds of music? Any particular performers and composers? When?

Because of all their influence, you might worry that research questions are very difficult to develop. Sometimes it can seem that way. But we'll help you get the hang of it and, luckily, none of us has to come up with perfect ones right off. It's more like doing a rough draft and then improving it. That's why we talk about developing research questions instead of just writing them.

Steps for Developing a Research Question

The steps for developing a research question, listed below, can help you organize your thoughts.

Step 1: Pick a topic (or consider the one assigned to you).

Step 2: Write a narrower/smaller topic that is related to the first.

Step 3: List some potential questions that could logically be asked in relation to the narrow topic.

Step 4: Pick the question that you are most interested in.

Step 5: Change the question you’re interested in so that it is more focused and specific.

ACTIVITY: Following the Steps

MOVIE: Developing Research Questions

As you view this short video on how to develop research questions, think about the steps. Which step do you think is easiest? Which do you think is the hardest?

Practice

Once you know the steps and their order, only three skills are involved in developing a research question:

- Imagining narrower topics about a larger one,

- Thinking of questions that stem from a narrow topic, and

- Focusing questions to eliminate their vagueness.

Every time you use these skills, it’s important to evaluate what you have produced—that's just part of the process of turning rough drafts into more finished products.

Maybe you have a topic in mind but aren't sure how to form a research question around it. The trick is to think of a question related to your topic but not answerable with a quick search. Also, try to be specific so that your research question can be fully answered in the final product for your research assignment.

ACTIVITY: Thinking of Questions

For each of the narrow topics below, think of a research question that is logically related to that topic. (Remember that good research questions often, but not always, start with “Why” or “How” because questions that begin that way usually require more analysis.)

Topics:

- U.S. investors’ attitudes about sustainability

- College students’ use of Snapchat

- The character Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird

- Nature-inspired nanotechnologies

- Marital therapy

After you think of each research question, evaluate it by asking whether it is:

- Logically related to the topic

- In question form

- Not answerable with a quick Google search

- Specific, not vague

Sometimes the first draft of a research question is still too broad, which can make your search for sources more challenging. Refining your question to remove vagueness or to target a specific aspect of the topic can help.

ACTIVITY: Focusing Questions

The first draft research questions below are not focused enough. Read them and identify at least one area of vagueness in each. Check your vagueness with what we identified. It’s great if you found more than we did because that can lead to research questions of greater specificity. See the bottom of the page for our answers.

First Drafts of Research Questions:

- Why have most electric car company start-ups failed?

- How do crabapple trees develop buds?

- How has NASA helped America?

- Why do many first-time elections soon after a country overthrows a dictator result in very conservative elected leaders?

- How is music composed and performed mostly by African-Americans connected to African-American history?

ACTIVITY: Developing a Research Question

ANSWER TO ACTIVITY: Focusing Questions

Some answers to the “Focusing Questions” Activity above are:

Question 1: Why have most electric car company start-ups failed?

Vagueness: Which companies are we talking about? Worldwide or in a particular country?

Question 2: How do crabapple trees develop buds?

Vagueness: There are several kinds of crabapples. Should we talk only about one kind? Does it matter where the crabapple tree lives?

Question 3: How has NASA helped America?

Vagueness: NASA has had many projects. Should we should focus on one project they completed? Or projects during a particular time period?

Question 4: Why do many first-time elections soon after a country overthrows a dictator result in very conservative elected leaders?

Vagueness: What time period are we talking about? Many dictators have been overthrown and many countries have been involved. Perhaps we should focus on one country or one dictator or one time period.

Question 5: How is music composed and performed mostly by African-Americans connected to African-American history?

Vagueness: What kinds of music? Any particular performers and composers? When?

Warm-up

What’s your overall view or philosophy around new technologies and tech tools? Eg., are you an ‘early adopter’ or prefer to wait until the bugs are worked out? Are you excited for our new robot overlords or are you a humanist through and through?

AI 'Pulse Check'

- Who is using GenAI?

- What are you using it for?

- What would you like to?

- What don’t you want to use it for?

- How do you feel about me using AI with our class work?

- What else?

Review Academic Code, Section V

Pima Community College Academic Integrity Code

URL: https://www.pima.edu/student-resources/student-policies-complaints/docs/academic-integrity-code.pdf

Review AI Guidelines

Students shall:

- Learn how to use AI text generators and other AI-based assistive resources (AI tools) to enhance rather than damage their developing abilities as writers, coders, communicators, and thinkers.

- Give credit to AI tools whenever used, even if only to generate ideas rather than usable text or illustrations.

- When using AI tools on assignments, add an appendix showing (a) a description of precisely which AI tools were used (e.g. ChatGPT, Grammarly, etc.), (b) an explanation of how the AI tools were used (e.g. to generate ideas)

- Employ AI detection tools and originality checks prior to submission, ensuring that their submitted work is not mistakenly flagged.

- Use AI tools wisely and intelligently, aiming to deepen understanding of subject matter and to support learning.

The instructor shall:

- Ensure fair grading for both those who do and do not use AI tools.

- Treat work by students who declare no use of AI tools as the baseline for grading.

- Employ tools and strategies to evaluate the degree to which AI tools have likely been employed.

- Impose a significant penalty for low-energy or unreflective reuse of material generated by AI tools and assigning zero points for merely reproducing the output from AI tools.

- Employ AI tools responsibly and transparently in the performance of their teaching responsibilities

For Further Reading

A Student Guide to Navigating College in the Artificial Intelligence Era

The Writing Process

When we talk about "the writing process" what we really mean is a series of steps that help you organize your thoughts, develop your ideas, and refine your work into a polished piece of writing. It usually begins with prewriting, where you brainstorm ideas, research your topic, and plan your approach. This stage is about exploring your thoughts freely, jotting down anything that comes to mind, and considering your audience and purpose. Once you have a clear idea, you'll move on to drafting, where you start putting your ideas into sentences and paragraphs. This is where you build the structure of your piece, focusing on getting your ideas down rather than making everything perfect right away.

| Brainstorming | Drafting | Revising | Editing | Publishing |

After drafting, you enter the revision stage, which is all about improving the content and clarity of your writing. You'll rework your ideas, reorganize sections, and make sure your arguments or narrative flow logically. Following that, you'll move on to editing, where you focus on the finer details like grammar, punctuation, and word choice. This step ensures your writing is clear, concise, and error-free. Finally, the publishing or submission stage is when you prepare your work for its final presentation, whether that’s handing it in to your professor, sharing it with peers, or publishing it online. As with most processes, it's normal to revisit earlier stages multiple times to refine your work.

There are a number of ways to organize your brainstorms get started writing, and the methods you use to organize, draft, and finalize your work are also unique to you as a writer. As such, it is important to find a way that works for you and this class is meant to help you with that. Below you will find four main ways to begin writing, including a mind map, and outline, freewriting, and using a grid.

Brainstorming: Four Ways to Begin

https://youtu.be/HSufG-AIQYo?si=DxGrlwn7nw0GFF9k

Mind Map

Mind mapping is a visual tool that helps you organize your thoughts and ideas by connecting them in a structured way. It starts with a central idea or topic, and from there, you branch out into related subtopics, each represented by a word or phrase. These subtopics can further branch out into more detailed points, creating a web-like structure that shows how your ideas are connected. Many writers like this method because the shapes show how the ideas relate or connect, and writers can find a focused topic from the connections mapped. Using idea mapping, you might discover interesting connections between topics that you had not thought of before.

To create an idea map, start with your general topic in a circle in the center of a blank sheet of paper. Then write specific ideas around it and use lines or arrows to connect them together. Add and cluster as many ideas as you can think of.

Outline

An outline is a structured plan for organizing your ideas before you start writing an essay or paper. It typically starts with your main topic or thesis at the top, followed by a hierarchical arrangement of main points and subpoints that support your thesis. Each main point is usually broken down into smaller details or evidence that you will cover in your writing. Creating an outline helps you to clearly see the overall structure of your essay, ensuring that your ideas flow logically and that you cover all necessary points. It serves as a roadmap to guide your writing process, making it easier to stay focused and organized.

There are two types of formal outlines: the topic outline and the sentence outline. You format both types of formal outlines in the same way.

- Place your introduction and thesis statement at the beginning, under roman numeral I.

- Use roman numerals (II, III, IV, V, etc.) to identify main points that develop the thesis statement.

- Use capital letters (A, B, C, D, etc.) to divide your main points into parts.

- Use arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.) if you need to subdivide any As, Bs, or Cs into smaller parts.

- End with the final roman numeral expressing your idea for your conclusion.

Here is what the skeleton of a traditional formal outline looks like. The indention helps clarify how the ideas are related.

- Introduction

- Thesis statement

- Main point 1 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 1

- Main point 2 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 2

- Main point 3 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 3

- Conclusion

Freewriting

Freewriting is a writing technique where you write continuously for a set period without worrying about grammar, punctuation, or spelling. The goal is to get your thoughts down on paper without censoring yourself or stopping to correct mistakes. This method helps you overcome writer’s block, discover new ideas, and develop your thoughts more fully.

Try writing for 3-5 minutes without stopping and try not to worry about grammar, spelling, or punctuation. Instead, write as quickly as you can. If you get stuck, just copy the same word or phrase over and over until you come up with a new thought.

When writing quickly, try not to doubt or question your ideas. Allow yourself to write freely and unselfconsciously. Once you start writing with few limitations, you may find you have more to say than you first realized. Since freewriting encourages a flow of ideas without judgment, it can be a valuable way to generate content that you can later refine and organize into a more structured piece. Your flow of thoughts can lead you to discover even more ideas about the topic. Freewriting may even lead you to discover another topic that excites you even more.

https://youtu.be/4O0EMX0nnl4?si=LeyARtpwzI210uZZ

Grid

A grid is a brainstorming tool that helps you organize and compare different ideas, topics, or aspects of your writing. It typically consists of a table with columns and rows where you can list out different categories or criteria in the columns and fill in related ideas or details in the rows. This method allows you to visually organize your thoughts and see how different elements relate to one another. For example, you might use a grid to compare themes across multiple texts, explore pros and cons of various arguments, or brainstorm different angles on a topic. Using a grid can help you identify patterns, gaps, and connections in your ideas, making it easier to decide what to focus on when you start writing.

This doesn’t need to be anything too formal; just jot down the main points you want to make, any supporting evidence or examples you plan to use, and the order in which you want to present them. An outline will serve as your roadmap and help you stay focused as you write.

Example: Rhetorical Strategies Grid

| Passage (Quote or Paraphrase) | Passage | Passage | |

| Idea or Example | |||

| Idea or Example | |||

| Idea or Example | “Though many kinds of physical work don’t require a high literacy level, more reading occurs in the blue-collar workplace than is generally thought, from manuals and catalogues to work orders and invoices, to lists, labels, and forms. With routine tasks, for example, reading is integral to understanding production quotas, learning how to use an instrument, or applying a product. Written notes can initiate action, as in restaurant orders or reports of machine malfunction, or they can serve as memory aids.” |

This passage represents a claim of fact because Mike Rose shows that while many people don’t think that those in blue-collar jobs read much at work, this is actually false. In truth, Mike Rose says, blue-collar workers read quite a lot, especially while completing the routine tasks of their jobs. |

This claim of fact about how much a blue-collar worker reads on the job contributes to the audience’s overall understanding that blue-collar workers actually do exert mental energy on tasks at work that illustrate their critical thinking and literacy skills. After reading this passage, the intended audience would see that there are many ways of reading that we don’t normally think about, and that blue-collar workers often engage in these ways of reading. |

Example: Research Synthesis Grid

| Source One | Source Two | Source Three | |

| Idea | |||

| Idea | |||

| Idea | Cornelsen - Women accredited the WASP program for opening new doors, challenging stereotypes, and proving that women were as capable as men (p. 113) - Women could compete with men as equals in the sky because of their exemplary performance (p. 116) - WASP created opportunities for women that had never previously existed (p. 112) - Women’s success at flying aircrafts “marked a pivotal step towards breaking the existing gender barrier” (p. 112) |

Stewart - WAAC (Women’s Army Auxiliary Corp) was 1st chance for women to serve in army, given full army status in 1943 as WAC (p. 28) - Needs of the war were so great that women’s traditional social roles were ignored (p. 30) - Military women paid well for the time period and given benefits if they became pregnant (p. 32) - The 1940’s brought more opportunities to women than ever before (p. 26) |

Scott - Women born in the 1920’s found new doors open to them where they once would have encountered brick walls (p. 526) -Even women not directly involved in the war were changing mentally by being challenged to expand their horizons because of the changing world around them (p. 562) - War also brought intellectual expansion to many people (p. 557) |

What is Information Literacy?

Information Literacy, as a term, means understanding, finding, evaluating, and using information through intentionally applying reasoning, discernment, and decision making skills.

The Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals defines information literacy as “knowing when and why you need information, knowing where to find it, and how to evaluate, use and communicate it in an ethical manner.”

Practicing information literacy engages a set of skills that enable us to critically assess the quality and credibility of information from various sources, including digital, print, and media. Information literacy is crucial in our world, where of course, the sheer volume of available information can be overwhelming and not always reliable or accurate.

Key components of information literacy

- Identifying Information Needs: Understanding what information is needed for a particular purpose.

- Finding Information: Knowing how and where to locate relevant information using a variety of resources such as databases, libraries, and the internet.

- Evaluating Information: Assessing the credibility, accuracy, and reliability of the information found, considering factors such as the source, bias, and context.

- Using Information: Effectively applying the information to solve problems, make decisions, or create new knowledge, while also respecting ethical and legal considerations, such as avoiding plagiarism.

- Communicating Information: Presenting information in a clear, organized, and appropriate manner for the intended audience.

Information Literacy Models

There are several established models for information literacy that provide frameworks and guidelines for teaching and practicing information literacy skills.

The Big6 is one of the most widely known information literacy models. It breaks down the information literacy process into six steps.

The Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education describes the concept of information literacy as a spectrum of abilities rather than a set of skills

The CRAAP (Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose) test method has recently come under scrutiny but has been a common strategy across higher education

The SIFT method is an evaluation strategy developed by digital literacy expert, Mike Caulfield, to help determine whether online content can be trusted for credible or reliable sources of information

https://youtu.be/SHNprb2hgzU?si=AmvuEA5J23ssrsPl

Understanding Information Biases

Sometimes when we pick and choose information, our own biases and lived experiences lead us to seek certain sources over others. It is human to have bias, but understanding them when we seek information is crucial in a well-rounded approach to learning something new.

One type of bias we should consider is confirmation bias, which occurs when we only seek out evidence that confirms what we already believe or interpret evidence in a way that confirms our existing beliefs.

Let’s apply these ideas to the common practice of searching the internet for information. By recognizing cognitive biases, you can find the most accurate and reliable information:

- First, search results for “are we eating too much protein”

- Next, search results for “protein nutrition”

Notice the difference between the search terms “are we eating too much protein” and “protein nutrition.” The first gives results that indicate eating too much protein is bad. Authors that have this viewpoint are more likely to use the words “too much protein” than people who do not. The search “protein nutrition” gives results that are more neutral. Only using terms that frame a topic a certain way will produce biased results. It is similar to asking a leading question (Did you have a great day?) vs. a neutral question (How was your day?).

When reading information that opposes our personal viewpoints, we may be more likely to dismiss an author’s arguments. Since false consensus bias leads us to believe that others think the same way we do, it can be hard to accept that others have different beliefs that are also valid.

To avoid this type of bias, called a false consensus bias, approach the information like a scientist with a hypothesis. Acknowledge your hypothesis and be willing to accept that the hypothesis may be wrong. In science, a wrong hypothesis is celebrated as learning something new. I encourage us to let it be the same when exploring information and developing information literacy.

Information Literacy in-Depth

https://youtu.be/GoQG6Tin-1E?si=lRdBFgUv65rAMoPk

https://youtu.be/q-Y-z6HmRgI?si=UlvKsoxfPeTFZCYG

Information biases material adapted from: First-Year Composition Copyright © 2021 by Jackie Hoermann-Elliott

Academic Writing

What Is “Academic” Writing? by L. Lennie Irvin

What Are We Being Graded On? by Jeremy Levine

So You’ve Got a Writing Assignment. Now What? by Corrine E. Hinton

Weaving Personal Experience into Academic Writing by Marjorie Stewart

What’s That Supposed to Mean? Using Feedback on Your Writing by Jillian Grauman

Artificial Intelligence

A Student Guide to Navigating College in the Artificial Intelligence Era

Formatting & Citations

MLA stands for the Modern Language Association, and its style guidelines have been assisting authors since 1951. In 2016, the MLA Handbook introduced a template using core elements in an effort to simplify much of the documentation process in MLA format. In 2021, the ninth edition was expanded with considerably more content and visuals.

APA stands for the American Psychological Association and is the format designed for use within the field of psychology. However, other disciplines use APA as well, so always use the format your professor chooses.

When we talk about "the writing process" what we really mean is a series of steps that help you organize your thoughts, develop your ideas, and refine your work into a polished piece of writing. It usually begins with prewriting, where you brainstorm ideas, research your topic, and plan your approach. This stage is about exploring your thoughts freely, jotting down anything that comes to mind, and considering your audience and purpose. Once you have a clear idea, you'll move on to drafting, where you start putting your ideas into sentences and paragraphs. This is where you build the structure of your piece, focusing on getting your ideas down rather than making everything perfect right away.

| Brainstorming | Drafting | Revising | Editing | Publishing |

After drafting, you enter the revision stage, which is all about improving the content and clarity of your writing. You'll rework your ideas, reorganize sections, and make sure your arguments or narrative flow logically. Following that, you'll move on to editing, where you focus on the finer details like grammar, punctuation, and word choice. This step ensures your writing is clear, concise, and error-free. Finally, the publishing or submission stage is when you prepare your work for its final presentation, whether that’s handing it in to your professor, sharing it with peers, or publishing it online. As with most processes, it's normal to revisit earlier stages multiple times to refine your work.

There are a number of ways to organize your brainstorms get started writing, and the methods you use to organize, draft, and finalize your work are also unique to you as a writer. As such, it is important to find a way that works for you and this class is meant to help you with that. Below you will find four main ways to begin writing, including a mind map, and outline, freewriting, and using a grid.

Brainstorming: Four Ways to Begin

https://youtu.be/HSufG-AIQYo?si=DxGrlwn7nw0GFF9k

Mind Map

Mind mapping is a visual tool that helps you organize your thoughts and ideas by connecting them in a structured way. It starts with a central idea or topic, and from there, you branch out into related subtopics, each represented by a word or phrase. These subtopics can further branch out into more detailed points, creating a web-like structure that shows how your ideas are connected. Many writers like this method because the shapes show how the ideas relate or connect, and writers can find a focused topic from the connections mapped. Using idea mapping, you might discover interesting connections between topics that you had not thought of before.

To create an idea map, start with your general topic in a circle in the center of a blank sheet of paper. Then write specific ideas around it and use lines or arrows to connect them together. Add and cluster as many ideas as you can think of.

Outline

An outline is a structured plan for organizing your ideas before you start writing an essay or paper. It typically starts with your main topic or thesis at the top, followed by a hierarchical arrangement of main points and subpoints that support your thesis. Each main point is usually broken down into smaller details or evidence that you will cover in your writing. Creating an outline helps you to clearly see the overall structure of your essay, ensuring that your ideas flow logically and that you cover all necessary points. It serves as a roadmap to guide your writing process, making it easier to stay focused and organized.

There are two types of formal outlines: the topic outline and the sentence outline. You format both types of formal outlines in the same way.

- Place your introduction and thesis statement at the beginning, under roman numeral I.

- Use roman numerals (II, III, IV, V, etc.) to identify main points that develop the thesis statement.

- Use capital letters (A, B, C, D, etc.) to divide your main points into parts.

- Use arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.) if you need to subdivide any As, Bs, or Cs into smaller parts.

- End with the final roman numeral expressing your idea for your conclusion.

Here is what the skeleton of a traditional formal outline looks like. The indention helps clarify how the ideas are related.

- Introduction

- Thesis statement

- Main point 1 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 1

- Main point 2 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 2

- Main point 3 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 3

- Conclusion

Freewriting

Freewriting is a writing technique where you write continuously for a set period without worrying about grammar, punctuation, or spelling. The goal is to get your thoughts down on paper without censoring yourself or stopping to correct mistakes. This method helps you overcome writer’s block, discover new ideas, and develop your thoughts more fully.

Try writing for 3-5 minutes without stopping and try not to worry about grammar, spelling, or punctuation. Instead, write as quickly as you can. If you get stuck, just copy the same word or phrase over and over until you come up with a new thought.

When writing quickly, try not to doubt or question your ideas. Allow yourself to write freely and unselfconsciously. Once you start writing with few limitations, you may find you have more to say than you first realized. Since freewriting encourages a flow of ideas without judgment, it can be a valuable way to generate content that you can later refine and organize into a more structured piece. Your flow of thoughts can lead you to discover even more ideas about the topic. Freewriting may even lead you to discover another topic that excites you even more.

https://youtu.be/4O0EMX0nnl4?si=LeyARtpwzI210uZZ

Grid

A grid is a brainstorming tool that helps you organize and compare different ideas, topics, or aspects of your writing. It typically consists of a table with columns and rows where you can list out different categories or criteria in the columns and fill in related ideas or details in the rows. This method allows you to visually organize your thoughts and see how different elements relate to one another. For example, you might use a grid to compare themes across multiple texts, explore pros and cons of various arguments, or brainstorm different angles on a topic. Using a grid can help you identify patterns, gaps, and connections in your ideas, making it easier to decide what to focus on when you start writing.

This doesn’t need to be anything too formal; just jot down the main points you want to make, any supporting evidence or examples you plan to use, and the order in which you want to present them. An outline will serve as your roadmap and help you stay focused as you write.

Example: Rhetorical Strategies Grid

| Passage (Quote or Paraphrase) | Passage | Passage | |

| Idea or Example | |||

| Idea or Example | |||

| Idea or Example | “Though many kinds of physical work don’t require a high literacy level, more reading occurs in the blue-collar workplace than is generally thought, from manuals and catalogues to work orders and invoices, to lists, labels, and forms. With routine tasks, for example, reading is integral to understanding production quotas, learning how to use an instrument, or applying a product. Written notes can initiate action, as in restaurant orders or reports of machine malfunction, or they can serve as memory aids.” |

This passage represents a claim of fact because Mike Rose shows that while many people don’t think that those in blue-collar jobs read much at work, this is actually false. In truth, Mike Rose says, blue-collar workers read quite a lot, especially while completing the routine tasks of their jobs. |

This claim of fact about how much a blue-collar worker reads on the job contributes to the audience’s overall understanding that blue-collar workers actually do exert mental energy on tasks at work that illustrate their critical thinking and literacy skills. After reading this passage, the intended audience would see that there are many ways of reading that we don’t normally think about, and that blue-collar workers often engage in these ways of reading. |

Example: Research Synthesis Grid

| Source One | Source Two | Source Three | |

| Idea | |||

| Idea | |||

| Idea | Cornelsen - Women accredited the WASP program for opening new doors, challenging stereotypes, and proving that women were as capable as men (p. 113) - Women could compete with men as equals in the sky because of their exemplary performance (p. 116) - WASP created opportunities for women that had never previously existed (p. 112) - Women’s success at flying aircrafts “marked a pivotal step towards breaking the existing gender barrier” (p. 112) |

Stewart - WAAC (Women’s Army Auxiliary Corp) was 1st chance for women to serve in army, given full army status in 1943 as WAC (p. 28) - Needs of the war were so great that women’s traditional social roles were ignored (p. 30) - Military women paid well for the time period and given benefits if they became pregnant (p. 32) - The 1940’s brought more opportunities to women than ever before (p. 26) |

Scott - Women born in the 1920’s found new doors open to them where they once would have encountered brick walls (p. 526) -Even women not directly involved in the war were changing mentally by being challenged to expand their horizons because of the changing world around them (p. 562) - War also brought intellectual expansion to many people (p. 557) |