Rhetorical Situation

The term “rhetorical situation” refers to the circumstances that bring written, visual, and other texts into existence. Understanding the rhetorical situation of the texts we’re consuming will help us make choices about their relevancy and trustworthiness. It will also help us understand the topic we’re learning about more holistically. Why was that particular video, infographic, or article made? Who is it really for? What is the creator gaining from it?

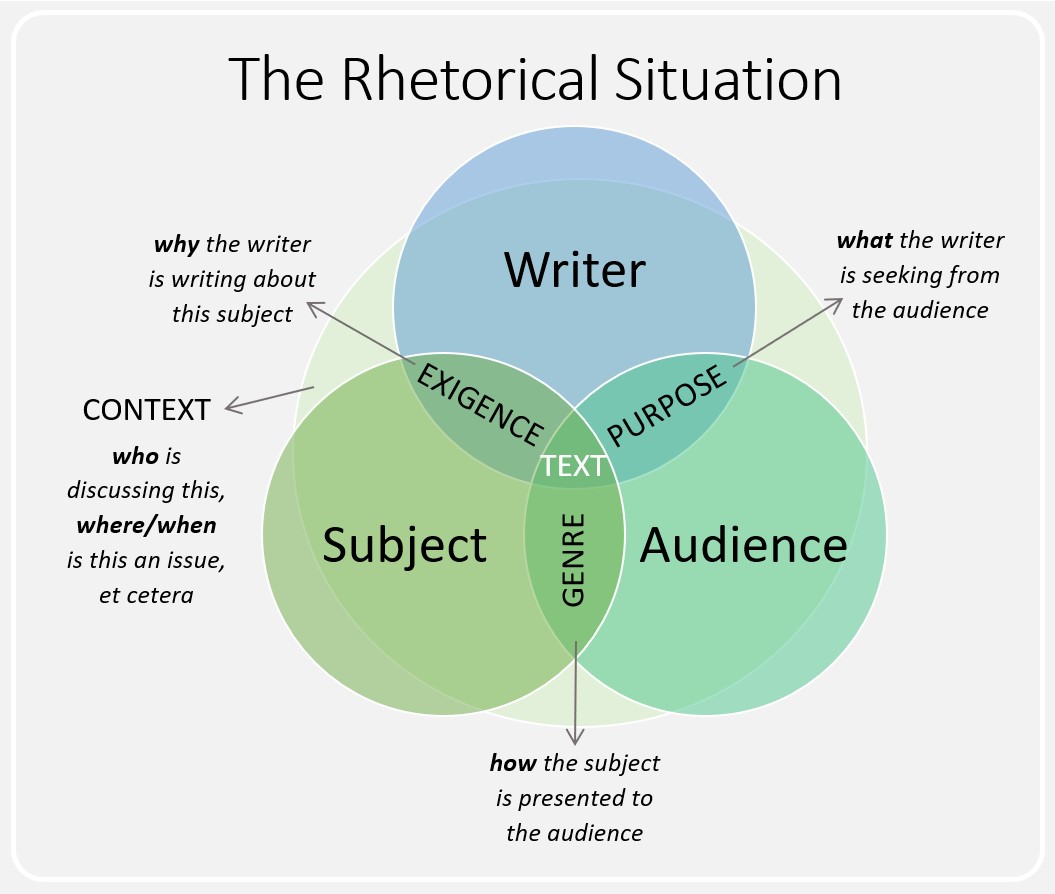

Any time anyone is trying to make an argument, they’re doing so out of a particular context, one that influences and shapes the argument that is being made. Classical Rhetoric defines the elements of the Rhetorical Situation in the diagram below.

Rhetorical Context

A simpler chart demonstrates similar relationships in the form of a pyramid. Either works!

The three key factors–purpose, author, and audience–all work together to influence what the text itself says, and how it says it. Let’s examine each of the three in more detail.

Purpose

An author’s purpose in communicating could be to instruct, persuade, inform, entertain, educate, startle, excite, sadden, enlighten, punish, console, or many, many others.

Like authors, audiences have varied purposes for reading, listening to, or otherwise appreciating pieces of communication. Audiences may seek to be instructed, persuaded, informed, entertained, educated, startled, excited, saddened, enlightened, punished, consoled, or many, many others.

Authors’ and audiences’ purposes are only limited to what authors and audiences want to accomplish in their moments of communication.

Any time you are preparing to write, you should first ask yourself, “Why am I writing?” All writing, no matter the type, has a purpose. Purpose will sometimes be given to you (by a teacher, for example), while other times, you will decide for yourself. As the author, it’s up to you to make sure that purpose is clear not only for yourself, but also–especially–for your audience. If your purpose is not clear, your audience is not likely to receive your intended message.

There are, of course, many different reasons to write (e.g., to inform, to entertain, to persuade, to ask questions), and you may find that some writing has more than one purpose. When this happens, be sure to consider any conflict between purposes, and remember that you will usually focus on one main purpose as primary.

Bottom line: Thinking about your purpose before you begin to write can help you create a more effective piece of writing.

Audience

The Audience refers to any recipient of communication: the individuals the writer engages with the text. Most often there is an intended, or target, audience for the text. Audiences encounter and in some way use the text based on their own experiences, values, and needs that may or may not align with the writer’s.

In order for your writing to be maximally effective, you have to think about the audience you’re writing for and adapt your writing approach to their needs, expectations, backgrounds, and interests. Being aware of your audience helps you make better decisions about what to say and how to say it. For example, you have a better idea if you will need to define or explain any terms, and you can make a more conscious effort not to say or do anything that would offend your audience.

Sometimes you know who will read your writing – for example, if you are writing an email to your boss. Other times you will have to guess who is likely to read your writing – for example, if you are writing a newspaper editorial. You will often write with a primary audience in mind, but there may be secondary and tertiary audiences to consider as well.

Author

The final unique aspect of anything written down is who it is, exactly, that does the writing.

An author refers to anyone who composes communication. An author could be one person or many people. An author could be someone who uses writing (like in a book), speech (like in a debate), visual elements (like in a TV commercial), audio elements (like in a radio broadcast), or even tactile elements (as is used in making Braille) to communicate. Whatever authors create, authors are human beings whose particular activities are affected by their individual backgrounds.

In some sense, authorship is the part you have the most control over–it’s you who’s writing, after all! You can harness the aspects of yourself that will make the text most effective to its audience, for its purpose. Analyzing yourself as an author allows you to make explicit why your audience should pay attention to what you have to say, and why they should listen to you on the particular subject at hand.

How to Use Rhetoric To Get What You Want

Material adapted from Fundamentals of Composition Copyright © by Lumen Learning