Thinking about the Writing Process

Patricia Lynne

Writing has a trajectory. You begin with an assignment or a desire to write, and you end with a final product. The in-between parts vary substantially from person to person and even task to task, which means that you may have multiple processes. But the overall trajectory for writing tasks is similar enough that we can talk about it.

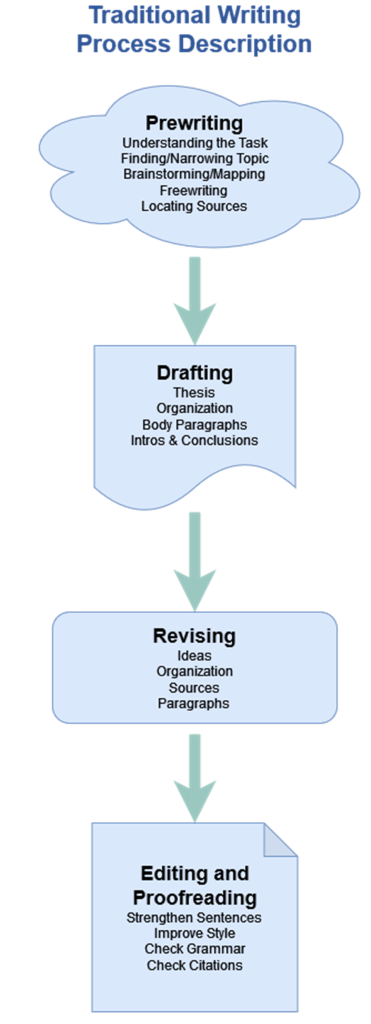

You may have seen diagrams of the process that look something like the one on the right. It’s a bit over simplified, but in general, the writing process has frequently been described in relatively linear terms as a movement from prewriting to drafting to revising to editing and proofreading.

You may also have heard that this process is recursive. This means that writers frequently go back to earlier stages when, for example, they discover a new idea that needs additional prewriting and drafting work before it can be incorporated in a revision. Sometimes such recursion will appear as arrows linking the stages in reverse.

Some models will include feedback from readers, usually in between the drafting and revising stage. Feedback at this stage usually helps writers refine their drafts and produce better revisions.

This image presents a relatively neat process, and it implies that if you just follow the steps, you’ll come out with a finished project. But the process is rarely this neat—or even neat at all.

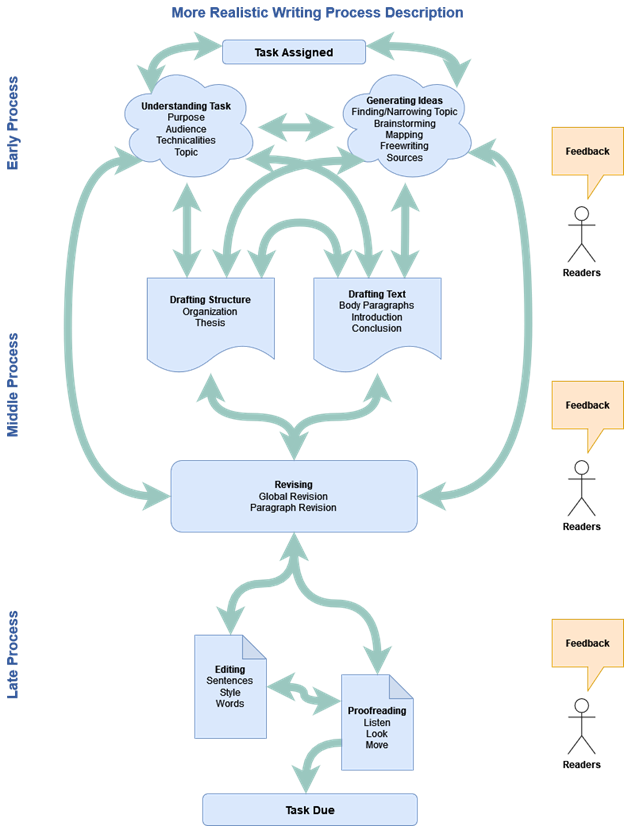

Compare this with the model depicted in the image below. The trajectory stays the same (assignment to final version), but there can be a lot of variation as we move through the “stages” in between:

- Some writers like to get their ideas out on paper or screen quickly, folding prewriting into writing and revising.

- Some writers like to think long and hard about what they are going to write before ever touching the keyboard.

- Some writers like to write the perfect introduction before they do anything else.

- Some like to skip the introduction until the end of the first draft.

- Some want to read everything they are going to write about first; some want to read as they go.

None of these approaches is “right” or “wrong.”

This text describes a writing process trajectory as represented in this image. At each “stage,” I present a range of techniques and strategies for that kind of work.

As you use this text, try focusing more on what you are trying to accomplish by writing instead of the order of the stages. While it is important to keep making progress on an assignment, it is actually more important to recognize, for example, whether you are ready to revise or whether you need to go back to the assignment itself to focus on your purpose.

With each of the strategies I suggest, your mileage may vary. My recommendation is that you try them with an open mind, particularly the ones that your instructor recommends. Be ready to consider approaches that have not worked for you in the past or that you have never tried. You might find something new that will help you write more successfully.

Procrastination

Economy vs. Copia

Before we get too far into “the process,” I want to think about general attitudes and habits toward writing.

Let’s start with the “I hate writing” attitude that quite a few students have expressed to me over the years. If you hate writing now, I’m not going to promise that you’ll come out on the other side of this text or this course loving writing—or even necessarily hating it less. But I have designed this book to help you feel more comfortable with writing because you’ll know more about how to succeed in the writing tasks that you’ll be given in college.

Even if you don’t hate writing, you may have developed an attitude or habit around writing that is particularly harmful: economy in writing. Students are very busy people. Technically, if you are taking a full load of courses, you should be working more than forty hours a week on your academics. As a result, students tend to think that they should only write only to the minimum word count and then stop.

More than 40 hours?

According to federal regulation 34 CFR 600.2, a credit hour is defined as one hour of instruction plus two hours of work outside of instruction (Code). While there are adjustments and exceptions (for courses like labs), in short, this means that each credit hour requires three hours of work from you—generally one in the classroom with the instructor and two outside on your own.

I know this is a writing textbook, but let’s do a little math. If you are taking a 3-credit course, then, you should be putting in nine hours, and if you are taking a 4-credit course, you should be putting in twelve.

If you are taking five 3-credit courses (a typical full load in many institutions), you’re expected to put in 45 hours between class and preparation time.

If you are taking four 4-credit courses (again, a typical full load), you’re expected to put in 48 hours.

So, yes, really. More than 40 hours.

Students who write economically rarely produce more than a first draft. Remember what I said about one-night wonders? Those first drafts might be good enough, but they won’t be your best work. Not everything in our first drafts is really that good. In the process of writing this book, for example, I have probably thrown out nearly as many words as I have written—if not more.

In an economic approach, you end up turning in subpar work, keeping words you have produced just because you have produced them.

In copia (from Latin, meaning “abundance”), writers write a lot. They produce words freely, writing more than the assignment requires so that they can find the best 900 words in the 1500 that they have produced. When writers—including students—take this approach, we are able to produce better writing because we have more to choose from.

One key thing to know here is that copia doesn’t really take more time than economy. If you have ever written economically, think about how long you stared at a blank screen or piece of paper, agonizing over what to say and how to say it “right.” You probably didn’t save any time over jumping in and writing whatever you were thinking, even if those thoughts weren’t very coherent and didn’t quite fit into the project at hand.

If you had jumped in and started writing, you might have pushed your thinking into better territory faster, and some of what you wrote might have actually been good enough for your final version, even if you ended up throwing out a bunch of words.

If you have been an economic writer in the past, this might be a good moment for change.

Key Points: Thinking about Writing Process

- There is no single writing process.

- Your process is likely to be complex, but that’s not a problem.

- You will never produce your best writing at the last minute.

- If you allow yourself to produce more words than you need for the assignment, you will have choices.

1. Start by Thoroughly and Critically Reading the Text

- Practice skimming the text first, then committing to a thorough reading

- Take good notes!

2. Understand the Purpose and Argument

- Identify the Thesis:

- Start by identifying the central claim or thesis of the text. What is the author trying to argue or prove?

- Ex: In Brooks' article, the thesis centers around moral decline being the cause of societal issues like loneliness and meanness.

- Analyze the Author’s Purpose:

- Why did the author write this piece? Is the goal to persuade, inform, provoke, or entertain? Understanding the purpose will help students evaluate the effectiveness of the text.

3. Contextualize the Text

- Historical and Cultural Context:

- Consider the time period and societal issues during which the text was written. How does the context influence the content?

- Ex: Brooks' article reflects concerns about modern American society and the breakdown of community.

- Author’s Background:

- What do we know about the author, and how might their perspective, biases, or experiences shape the text? Analyzing David Brooks’ background as a political commentator helps us see how his perspective informs the argument.

4. Analyze the Structure and Organization

- Text Organization:

- Look at how the text is structured. Does it follow a logical progression? Is the argument easy to follow, or is it fragmented? A well-structured argument is key to persuasiveness.

- Ex: Brooks starts by presenting the problem (increased sadness and meanness) and then provides a historical analysis before suggesting solutions. Is this structure effective?

- Sections and Transitions:

- How does the author transition between ideas? Are there clear topic sentences and smooth connections between paragraphs?

5. Examine the Language and Style

- Tone and Voice:

- Identify the tone of the text. Is it formal, conversational, ironic, or passionate? The tone will affect how the audience perceives the message.

- Ex: Brooks uses a reflective and sometimes concerned tone. How does that affect the way readers relate to his argument?

- Language/Word Choice:

- What kind of language does the author use? Is it simple, academic, emotional, or loaded with jargon? Pay attention to any metaphors, analogies, or symbolism that enhance the argument.

- Ex: Brooks uses phrases like "moral formation" and "emotional, relational, and spiritual crisis." How do these choices influence how we interpret the severity of the problem he describes?

6. Evaluate the Use of Evidence

- Types of Evidence:

- Analyze what kind of evidence the author provides (statistics, historical examples, expert testimony, anecdotes). Is the evidence convincing? Why or why not?

- Ex: Brooks uses data (e.g., statistics on depression and loneliness), historical references, and sociological observations. Are these types of evidence are effective for his argument.

- Reliability of Sources:

- Are the sources credible? If the author relies heavily on specific data or studies, do they come from reputable sources?

7. Identify the Rhetorical Appeals (Ethos, Logos, Pathos)

- Ethos (Credibility):

- How does the author establish credibility? Does the writer appear knowledgeable or trustworthy? How does the author’s background play a role in building ethos?

- Logos (Logic and Reasoning):

- Examine the logical structure of the argument. Is it sound, or are there any logical fallacies? Does the author use facts and reason to support their argument effectively?

- Pathos (Emotion):

- How does the author appeal to the reader’s emotions? Does the author use language that aims to evoke a particular feeling or reaction?

8. Consider Biases and Assumptions

- Author Bias:

- Every author writes with a perspective shaped by their experiences and beliefs. Identify any potential biases or assumptions that may influence the argument.

- Ex: Does Brooks have a bias toward traditional values or certain societal structures? How does this shape his argument about the decline of moral education?

- Reader Bias:

- How might the reader’s background or beliefs influence how they interpret the text? Reflect on how your own biases and experiences might affect your reading.

9. Examine Counterarguments

- Acknowledgment of Opposing Views:

- Does the author address potential counterarguments? How does the author handle opposing viewpoints? If the text doesn’t acknowledge other perspectives, is that a weakness?

- Ex: Brooks briefly mentions other causes of societal problems, like social media and economic inequality, but then argues they don’t address the core issue of moral decline. Is this sufficient, or does he downplay important factors?

10. Reflect on Overall Effectiveness

- Is the Argument Convincing?:

- Form an opinion on whether the author’s argument is effective. What aspects of the text work well, and what might be lacking? Does the text achieve its intended purpose?

- Strengths and Weaknesses:

- What are the key strengths of the article? What weaknesses do you identify in terms of logic, evidence? What about in the rhetorical strategies like language, tone, and style?

Rhetorical Strategies Grid

Please use this template to find passages from your source text, interpret the passages, and connect the passages and interpretations to the author’s purpose and audience. You may copy this as a GoogleDocument here: Rhetorical Analysis Grid

First, answer the questions below for your text

- What is the text’s purpose(s)? Where do you find evidence of this?

- Who is the intended audience for the text? Where do you find evidence of this?

Then complete your grid

Note: fill it out as much as you can, but you don’t have to fill out a grid for every single example you find:

- Passage: Identify a passage that demonstrates a rhetorical strategy (ethos, logos, pathos) of your choice. You may include a direct quote or paraphrase.

- Interpretation and Explanation: Interpret and explain how the passage is an example of the rhetorical strategy.

- Impact on Purpose and Audience: Note how the strategy is impacting the author’s primary purpose and/or target audience. In other words, how would the audience interpret or respond to the strategy?

| Passage: either direct quote or paraphrase | Interpretation & explanation of how the passage is an example of the strategy you chose | Notes about how the passage would impact the purpose and/or audience. (How is this an example of the strategy “working” in the text?) | |

| Instance One | |||

| Instance Two | |||

| Instance Three |

Example: Brooks' "How America Got Mean"

1. What is the text’s purpose? Where do you find evidence of this?

- Purpose: Brooks’ primary purpose is to argue that America has become a meaner and lonelier society due to the decline of moral education and formative social institutions. He seeks to inform the reader about the historical and cultural factors that have led to this moral breakdown and encourage a rethinking of how moral education could be restored.

- Evidence: Brooks makes his purpose clear early on when he writes, "Why have Americans become so sad? Why have they become so mean?" He then spends much of the article tracing the shift away from moral formation, using historical references, statistics, and emotional appeals to argue that societal meanness is a direct result of the loss of moral education.

2. Who is the intended audience for the text? Where do you find evidence of this?

- Audience: The intended audience is likely well-educated, socially and politically engaged readers of The Atlantic. They are people who are concerned with cultural and societal issues and are familiar with debates about moral education, individualism, and community decline.

- Evidence: Brooks writes in a reflective and intellectual tone, assuming his audience is familiar with both historical context and sociological trends. The article’s placement in The Atlantic—a magazine known for its long-form journalism on politics and culture—also indicates that the readership consists of those interested in thoughtful social critique.

Rhetorical Strategies Grid:

|

Passage |

Interpretation & Explanation | Impact on Purpose and Audience |

|---|---|---|

| Instance One: "The percentage of people who say they don’t have close friends has increased fourfold since 1990." | Strategy: Logos - This passage uses statistics to appeal to logos (logical reasoning). By citing a clear, measurable statistic, Brooks grounds his argument in objective data, which adds credibility to his claim that American society is becoming more isolated. | The use of logos strengthens Brooks’ argument by providing the audience with concrete evidence of societal decline. The statistic likely resonates with his educated, socially conscious audience, who value fact-based arguments. This makes Brooks' claim more persuasive and harder to dismiss. |

| Instance Two: "We’re enmeshed in some sort of emotional, relational, and spiritual crisis." | Strategy: Pathos - This metaphor appeals to pathos (emotions), creating a vivid image of the depth of societal suffering. The use of words like "crisis" emphasizes urgency, encouraging the audience to feel concern and empathy for the state of society. | The emotional language helps Brooks connect with the reader on a personal level, making the issue of societal decline feel immediate and personal. By stirring concern, Brooks motivates the audience to reflect on the moral state of society and consider solutions, aligning with his purpose to spark reform. |

| Instance Three: "In 2018, a documentary about Mister Rogers called Won’t You Be My Neighbor? was released. People cried openly while watching it in theaters." | Strategy: Ethos & Pathos - Brooks references a well-known, morally respected figure—Mister Rogers—to build ethos (credibility) while also using an emotional appeal to pathos. By evoking the nostalgia and emotional responses associated with Mister Rogers, Brooks connects the audience to an idealized time of moral integrity. | This reference appeals to the audience's sense of nostalgia and emotion, making the argument about moral decline more relatable. The ethos of Mister Rogers serves to remind readers of what they believe society has lost, reinforcing Brooks’ purpose to argue for a return to moral education. It emotionally engages readers, urging them to reflect on societal changes and their personal values. |

Analysis Grid for Any Discipline

| Evidence/Passage | Observation & Explanation | Impact/Significance |

| Instance One | What is happening in this passage/data? What strategy or method is being used? Why is it significant? | How does this evidence support the main argument, research question, or hypothesis? How does it impact the audience or larger discussion? |

| Example (Literature): "She laughed no more, and her eyes were dim." (from The Story of an Hour) | Strategy: Symbolism – This line represents the death of hope and freedom for the protagonist. The dimming of her eyes symbolizes the end of her brief glimpse of liberation. | The use of symbolism adds emotional weight to the story’s theme of female repression. It leaves a lasting impact on readers, encouraging them to

reflect on gender roles in society. |

| Example (History): "The Treaty of Versailles placed full blame on Germany for the war." | Observation: The treaty uses attribution of blame as a political strategy. By assigning guilt, it justified harsh penalties and reparations against Germany. | The harshness of the treaty contributed to political and economic instability in Germany, laying the groundwork for the rise of fascism and WWII. This example highlights how short-term political decisions can have long-term global consequences. |

| Example (Business): "Apple’s Q3 earnings report showed a 20% increase in revenue from services like iCloud and Apple Music." | Strategy: The report uses data-driven evidence to show how Apple is diversifying beyond hardware sales, emphasizing growth in the services sector. | This growth in services demonstrates Apple's strategic shift towards recurring revenue models. It signals to investors that the company’s long-term profitability is less reliant on hardware, appealing to risk-averse stakeholders. |

| Example (Social Science): "Survey data shows that 60% of respondents experience job-related stress at least once a week." | Observation: The survey uses quantitative data to measure the prevalence of stress in the workplace. The percentage shows a widespread issue that impacts a significant portion of the workforce. | This data suggests that workplace stress is a systemic issue, which could lead to further studies on its impact on productivity and mental health. It might also support arguments for workplace policy reforms. |

| Example (Science): "The experiment showed that plants exposed to blue light grew 30% taller than those in red light." | Observation: The study uses controlled variables to demonstrate how light color affects plant growth. The comparison between blue and red light highlights a significant difference in growth rates. | This finding suggests a specific wavelength of light that could be optimized for agricultural practices. The analysis could lead to further research into how light spectrum manipulation affects plant biology, with practical applications in farming. |

Rhetorical Strategies Grid

Please use this template to find passages from your source text, interpret the passages, and connect the passages and interpretations to the author’s purpose and audience. You may copy this as a GoogleDocument here: Rhetorical Analysis Grid

First, answer the questions below for your text

- What is the text’s purpose(s)? Where do you find evidence of this?

- Who is the intended audience for the text? Where do you find evidence of this?

Then complete your grid

Note: fill it out as much as you can, but you don’t have to fill out a grid for every single example you find:

- Passage: Identify a passage that demonstrates a rhetorical strategy (ethos, logos, pathos) of your choice. You may include a direct quote or paraphrase.

- Interpretation and Explanation: Interpret and explain how the passage is an example of the rhetorical strategy.

- Impact on Purpose and Audience: Note how the strategy is impacting the author’s primary purpose and/or target audience. In other words, how would the audience interpret or respond to the strategy?

| Passage: either direct quote or paraphrase | Interpretation & explanation of how the passage is an example of the strategy you chose | Notes about how the passage would impact the purpose and/or audience. (How is this an example of the strategy “working” in the text?) | |

| Instance One | |||

| Instance Two | |||

| Instance Three |

Example: Brooks' "How America Got Mean"

1. What is the text’s purpose? Where do you find evidence of this?

- Purpose: Brooks’ primary purpose is to argue that America has become a meaner and lonelier society due to the decline of moral education and formative social institutions. He seeks to inform the reader about the historical and cultural factors that have led to this moral breakdown and encourage a rethinking of how moral education could be restored.

- Evidence: Brooks makes his purpose clear early on when he writes, "Why have Americans become so sad? Why have they become so mean?" He then spends much of the article tracing the shift away from moral formation, using historical references, statistics, and emotional appeals to argue that societal meanness is a direct result of the loss of moral education.

2. Who is the intended audience for the text? Where do you find evidence of this?

- Audience: The intended audience is likely well-educated, socially and politically engaged readers of The Atlantic. They are people who are concerned with cultural and societal issues and are familiar with debates about moral education, individualism, and community decline.

- Evidence: Brooks writes in a reflective and intellectual tone, assuming his audience is familiar with both historical context and sociological trends. The article’s placement in The Atlantic—a magazine known for its long-form journalism on politics and culture—also indicates that the readership consists of those interested in thoughtful social critique.

Rhetorical Strategies Grid:

| Passage | Interpretation & Explanation | Impact on Purpose and Audience |

|---|---|---|

| Instance One: "The percentage of people who say they don’t have close friends has increased fourfold since 1990." | Strategy: Logos - This passage uses statistics to appeal to logos (logical reasoning). By citing a clear, measurable statistic, Brooks grounds his argument in objective data, which adds credibility to his claim that American society is becoming more isolated. | The use of logos strengthens Brooks’ argument by providing the audience with concrete evidence of societal decline. The statistic likely resonates with his educated, socially conscious audience, who value fact-based arguments. This makes Brooks' claim more persuasive and harder to dismiss. |

| Instance Two: "We’re enmeshed in some sort of emotional, relational, and spiritual crisis." | Strategy: Pathos - This metaphor appeals to pathos (emotions), creating a vivid image of the depth of societal suffering. The use of words like "crisis" emphasizes urgency, encouraging the audience to feel concern and empathy for the state of society. | The emotional language helps Brooks connect with the reader on a personal level, making the issue of societal decline feel immediate and personal. By stirring concern, Brooks motivates the audience to reflect on the moral state of society and consider solutions, aligning with his purpose to spark reform. |

| Instance Three: "In 2018, a documentary about Mister Rogers called Won’t You Be My Neighbor? was released. People cried openly while watching it in theaters." | Strategy: Ethos & Pathos - Brooks references a well-known, morally respected figure—Mister Rogers—to build ethos (credibility) while also using an emotional appeal to pathos. By evoking the nostalgia and emotional responses associated with Mister Rogers, Brooks connects the audience to an idealized time of moral integrity. | This reference appeals to the audience's sense of nostalgia and emotion, making the argument about moral decline more relatable. The ethos of Mister Rogers serves to remind readers of what they believe society has lost, reinforcing Brooks’ purpose to argue for a return to moral education. It emotionally engages readers, urging them to reflect on societal changes and their personal values. |