Annotating and Note-Taking

Patricia Lynne

If you do not take notes as you read, you are wasting time and energy. Without notes, you will almost certainly have to reread substantial parts of the text to find passages that are important, and you will almost certainly lose track of the ideas you had as you were reading. While note-taking does slow down your reading, it greatly increases your overall reading efficiency. If you don’t make notes as you go, today’s great observation will likely become tomorrow’s forgotten detail.

There are many ways to take notes, and you need to find methods that work for you and your reading situation. Your annotation method will almost certainly vary depending on whether you are reading a hard copy or an e-version of a text.

You may also find that you need to take notes differently depending on the kind of text you are reading. For example, do you need the same kinds of notes for a textbook that contains information you will be tested on as you do for an article that you are going to write about? Be ready to alter your note-taking strategy so that your notes are most useful to you.

Understanding What to Take Notes About

You want to make sure you are capturing the main ideas in a text, but you also want to record your reactions to the text, particularly where they relate to your purpose for reading. For example, it doesn’t make sense to spend lots of time making notes about the history of an idea when your professor wants you to focus on the implications of that idea.

If you’ve been following the activities in this section, you already have two helpful guides as you read:

- First, you have any notes you made while pre-reading. Even if you didn’t take notes during this phase, you have information about the reading that you might decide to add to your notes as you go.

- You also have the list you made when you were focusing on the purpose for the reading. Refer to that list as you read to help you stay on task.

As you read, here are some particularly useful types of notes:

- Summaries or paraphrases of key ideas in the text

- Your responses, including your questions, points of agreement and disagreement, and notes about connections you see

- Informational notes, including definitions of words you aren’t familiar with and references to other sources

- Your comments on passages that are significant and that you might use in your own writing

Understanding How to Take Notes

Note-taking doesn’t look the same for everyone, and the method you choose will depend on the medium of the text (print or electronic), whether you can write on the text or not, and your preferences for things like color.

Writing Directly on Hard-Copy Texts

Through most of your K-12 education (and mine), you were probably told never to write in your textbooks, but now that you’re a college student, your teachers will tell you just the opposite. Writing in your texts as you read—annotating them—is encouraged! It’s a powerful strategy for engaging with a text.

Most college and university bookstores approve of textual annotation and don’t think it decreases a textbook’s value. In other words, you can annotate a college textbook and still sell it back to the bookstore later on if you choose to. You won’t get the full price you paid for the book, but you wouldn’t get that even if you don’t write in it at all, so you might as well take notes! Note that I say most—if you have questions and plan to sell back any textbooks, be sure to ask at the bookstore before you annotate.

Most textbook rental companies will let you do some limited writing and highlighting, but they often allow less than college bookstores. Be sure to read the fine print and FAQs about marking up a rental.

When annotating in a textbook or other double-sided printed material, pencil often works best. It won’t soak through the pages, which matters when you need to read the text or take notes on the other side. In addition, you can erase marks if you decide that what you originally wrote isn’t helpful. If you want to use ink, choose a ball-point pen rather than gel or permanent marker, since ball point ink is less likely to soak through. If using erasable pens, test in an inconspicuous area to make sure they actually erase on that paper.

Many students use brightly-colored highlighting pens to mark passages in texts. Highlighting alone, though, isn’t particularly helpful. Using highlighters creates big swaths of color in your text, but when you later go back to them, you may not remember why those passages were highlighted. If you want to use highlighters, be sure that every time you do, you also make a note so that you know why you highlighted that passage in the first place.

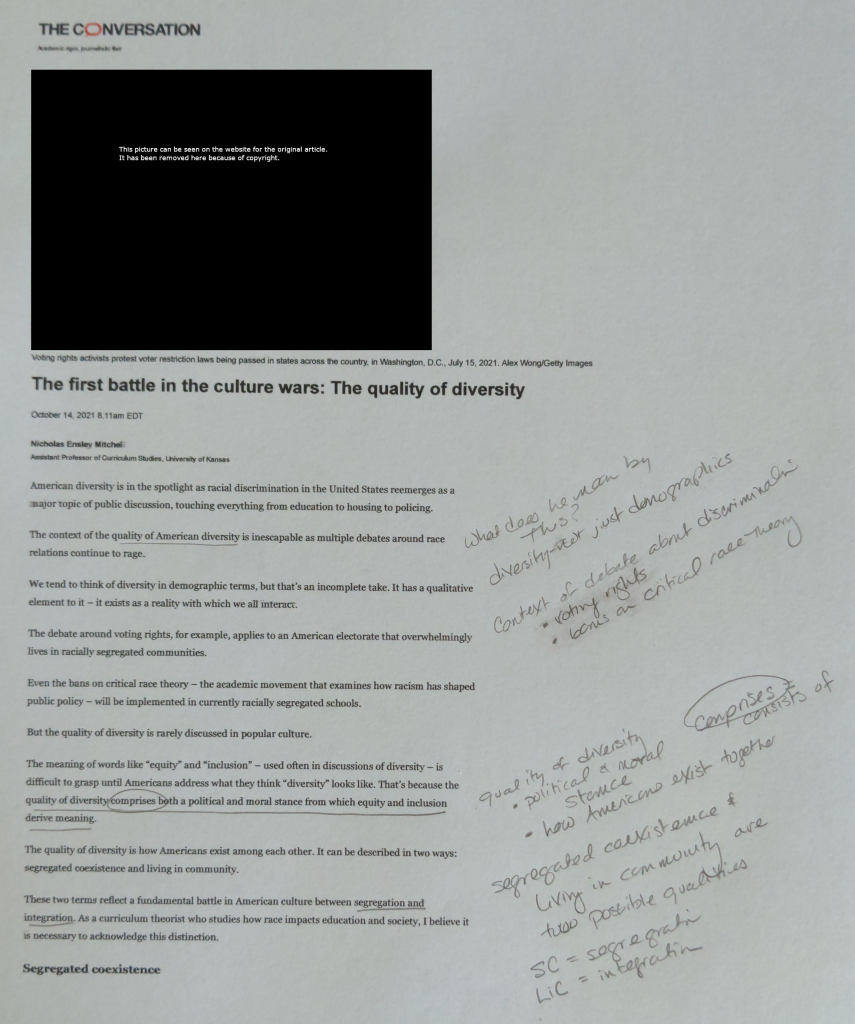

Here is a photograph of my notes on the first printed page of Mitchell’s article. I’ve done the notes in pencil, and if you look closely, you can see where I had to erase a mistake or two.

Taking Notes on Digital Texts

Many electronic books, particularly textbooks, often have on-board tools for note-taking as well as looking up words in dictionaries and encyclopedias. When they offer these tools, the companies usually provide guides or demos for using them. It’s worth taking a few minutes to look through those guides to learn what you can do.

Some annotation tools allow you to work collaboratively with others. Currently, Perusall and Hypothes.is are popular in higher education, and your professors may ask you to use them. Again, take a few minutes to learn how the note-taking system works before you start.

There are also many apps for annotating electronic files, including PDFs and web pages. You’ll need to try different ones to find something that works for you.

Keep in mind that the purpose of annotation on digital texts is exactly the same as on hard-copy texts. You want to make sure that you can use ideas and passages from the text for your learning and your assignments. If the tool gets in the way of that (and your professor isn’t requiring a specific tool), try something else.

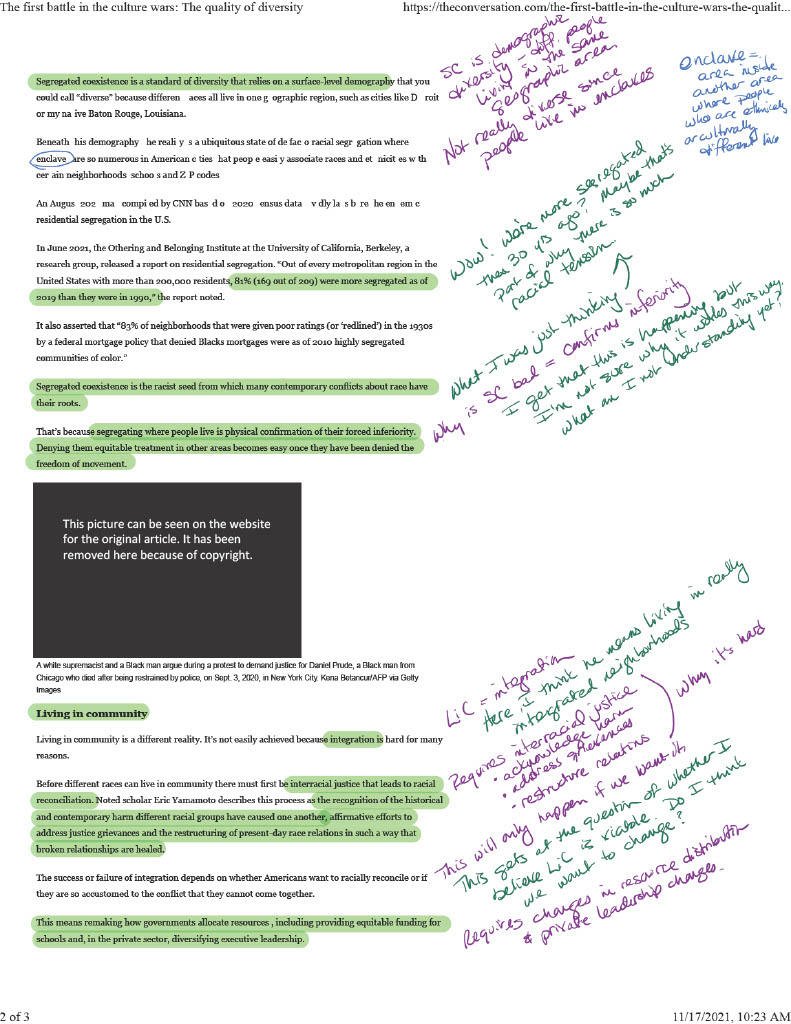

Here is a copy of my notes on the second page of the PDF of Mitchell’s article. These notes were done on my iPad with the app GoodNotes, which is my preferred notetaking method as of this writing. I use different colors: purple to indicate summary notes and green to indicate my responses, as well as blue for information I looked up.

Taking Notes Indirectly on Hard-Copy Texts

If you can’t write on the text itself, such as when you are using a library book, you can try copying or scanning the pages you need; however, if you need a lot of pages, this can become time consuming (and potentially expensive). Instead, you can take notes outside of the text—either by hand or electronically.

One way to do this is with sticky notes. Sticky notes give you the ability to attach your notes to the relevant pages and passages. The space is limited, but you can use multiple stickies if need be.

Alternatively, you can take notes on your own paper or in your word processor or an app. These methods give you as much space as you need. There is a risk of notes being separated from the text, but if you are careful about your organization, you should be able to find them when you need them.

Double-entry journaling is particularly useful when you need to keep track of both the main ideas in a text and your reactions, thoughts, and writing ideas as you are reading. In some ways, this can work even better than taking notes directly on the text because you aren’t bound by the size of the margins.

To set up a double-entry journal, create three columns. If you are doing this on paper, you can simply draw lines down the page. If you are doing this in a word processing document, you can set up a three-column table.

In the furthest left-hand column, make note of the location in the text. For print sources, pages and paragraph numbers are usually most helpful. For electronic sources, paragraph numbers are often most helpful.

In the middle column, you write summary only. This is so that you can clearly differentiate what the author is saying from your ideas. In the right-hand column, you write your responses and ideas. Your journal will look something like this:

| Location | Summary | Response |

| Intro ¶ 1-2, 4-5 | Diversity is pervasive in American culture now, in voting rights and housing and education. | I hear and read about it all the time. |

| Intro ¶ 3 | We usually think about diversity in terms of demographics. | How else would we think about it? |

| Intro ¶ 6-8 | Quality of diversity should be part of the conversation. Quality of diversity is “a political and moral stance from which equity and inclusion derive meaning.” It’s “how Americans exist among each other.” | Quality of diversity here sounds like we have choices about how we understand diversity and that if we understand it different ways, we can have things different from how they currently are. If this is true, then the definition of “quality” that Mitchell is using sounds a bit more like a characteristic than a standard, but there’s a bit of both here.

Definition Comprises = consists of |

| Intro ¶ 8-9 | Mitchell lists two possible qualities of diversity: “segregated co-existence” and “living in community.” He equates SC with segregation and LiC with integration. | This gets at the question whether I buy his framework. Do I think these are the only two options? SC sounds like what we live in now. Are there other options? I can’t think of any right now, but I want to come back to this as I work on the paper. |

Notice that every time you add a summary element, you also respond. Your journal will be most useful to you if you summarize frequently (at least every two or three paragraphs) and if you make a point of responding every time you summarize. If you are diligent about summarizing and responding, you will have a strong record of both your reading and your ideas for a paper when you are done reading. As a result, you will be in good shape to both understand and use what you have read.

Once again, it’s your turn, but this time, you should experiment. Using the guidance above, try at least two different ways of taking notes on a reading.

Once you’ve done taken the notes, reflect on the methods you tried. Which method(s) seem to work well for you? Why do you think it/they worked? Which method(s) did not work well for this reading? Why not?

Can you think of another reading situation where a different method would be better? What is that situation and what method(s) do you think would work better? Why?

Key Points: Annotating and Note-Taking

- No matter what you are reading for academic work, take notes!

- Take notes on the ideas in the text, but also take notes on your ideas as you read and any words or concepts you looked up. Also make sure that you are marking passages that might be useful for any project you are working on.

- Find note-taking methods that work for you, whether you write in books, on digital texts, or in your own notebooks or apps.

Text Attribution

This chapter contains material taken from the chapter “Annotate and Take Notes” from The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear and is used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

Generative AI Prompt

Explain to the AI tool what you are doing, and what you would like it to do. For example:

I am working on a rhetorical analysis in my writing class, and am looking for a text to analyze. (Please) Provide 12-15 recommendations of different types of texts (articles, TED talks, podcasts, etc) on the topic of ____.

- Include your topic, adjusting keywords as you see fit. For example, I had good results with a topic broken down like: homelessness, houselessness, and root causes in the USA. If your AI tool doesn't automatically generate a summary and direct link to the text you may prompt it to do so.

TED Talks (for Video and Audio Sources)

- Website: TED Talks

- What to look for: TED Talks are a great source for persuasive and engaging arguments.

Opinion and Editorial Sections (for Articles)

- Sources:

- What to look for: Opinion pieces in major newspapers provide clear arguments on current issues, perfect for rhetorical analysis. These pieces often aim to persuade readers on social, environmental, and political matters.

Podcasts and Interviews (for Audio Texts)

- Sources:

- What to look for: Podcasts often feature in-depth discussions on pressing issues with guest experts. They can serve as texts where students analyze the speaker’s rhetorical strategies and how effectively they engage listeners.

Environmental & Scientific Journals (for Articles and Reports)

- Sources:

- What to look for: Articles from environmental and scientific journals offer persuasive arguments backed by data and research, which are great for analyzing the logical appeal (logos) and use of evidence.

Documentaries and Video Essays (for Video Texts)

- Sources:

- What to look for: You might analyze how documentaries or video essays construct their argument using visuals, interviews, and data to make their case. They can focus on the documentary’s ability to persuade and convey urgency on important issues.

Academic and Advocacy Websites (for Articles, Reports, and Papers)

- Sources:

- What to look for: These websites offer research papers and reports that often take a clear stance on global issues, backed by research. These can be used to analyze how evidence and data (logos) are used to argue for change

Online (& Print) Magazines, including some available through PCC Library!

The Atlantic

- Focus: Politics, culture, social issues, technology, and more.

- Why it’s good: The Atlantic publishes well-researched opinion pieces and in-depth essays by respected writers. The articles often address current events and offer clear rhetorical strategies, making them great for analysis.

The New Yorker

- Focus: Commentary on politics, social issues, arts, culture, and literature.

- Why it’s good: The New Yorker is known for its narrative style and long-form journalism. There's a variety of texts to analyze, including persuasive essays, cultural critiques, or investigative reporting for tone, style, and rhetorical appeals.

Slate

- Focus: Politics, culture, technology, news commentary.

- Why it’s good: Slate’s articles are often conversational but make strong, persuasive arguments.

Vox

- Focus: Explanatory journalism covering politics, public policy, science, and culture.

- Why it’s good: Vox’s style is informative and analytical, often using data and research to explain complex issues. The authors often simplify complex information in and use visual rhetoric like charts or images.

Harper's Magazine

- Focus: Politics, culture, literature, arts, and society.

- Why it’s good: Harper’s features in-depth essays and long-form journalism that often take a critical stance on social and cultural issues, making it rich for rhetorical analysis, especially with complex arguments and high-level rhetoric.

The Economist

- Focus: Economics, business, politics, international affairs.

- Why it’s good: For students interested in analyzing more technical, data-driven texts, The Economist offers concise articles that rely on logical appeals and economic reasoning. It’s a great source for dissecting arguments based on facts and figures.

Wired

- Focus: Technology, innovation, culture, and science.

- Why it’s good: Wired’s articles often explore the intersection of technology and society, making it great for analyzing how technical information is made persuasive or relatable to a broader audience

National Geographic

- Focus: Science, environment, geography, history, and cultures.

- Why it’s good: Articles in National Geographic tend to focus on the environment, science, and culture, often using appeals to ethos and logos through expert testimony and data. You might analyze how scientific information is made persuasive to a general audience.

Scientific American

- Focus: Science, technology, health, and environmental issues.

- Why it’s good: If you're interested in science or technology, you can analyze how scientific facts and research are communicated and made persuasive to a broad audience, with a focus on ethos (credibility) and logos (logic).

Foreign Affairs

- Focus: International relations, global politics, and economics.

- Why it’s good: This publication focuses on foreign policy and global issues, providing well-structured arguments that are often analytical and fact-driven. Great for analyzing logical reasoning and appeals to authority.

Time Magazine

- Focus: News, politics, culture, and global events.

- Why it’s good: Time’s articles are generally concise and accessible, with clear arguments and rhetorical strategies that are easy for students to identify. It covers a wide range of current events.

The Guardian (US Edition)

- Focus: Politics, social justice, global issues, and culture.

- Why it’s good: The Guardian’s US edition covers many hot-button issues like race, inequality, and the environment. Their opinion and feature pieces are rich with persuasive strategies and provide a range of perspectives.

The Nation

- Focus: Progressive politics, social justice, environmental issues.

- Why it’s good: Known for its progressive stance, The Nation provides opinion pieces and investigative journalism on social and political issues. You might analyze its rhetorical strategies, particularly the appeals to emotion (pathos) and moral values (ethos)