Chapter 1.2: Who is Considered an Artist? Why Do We Make Art?

In much of the world today, an artist is considered to be a person with the talent and the skills to conceptualize and make creative works. Such persons are singled out and prized for their artistic and original ideas. Their art works can take many forms and fit into numerous categories, such as architecture, ceramics, digital art, drawings, mixed media, paintings, photographs, prints, sculpture, and textiles. Of greater importance, artists are the individuals who have the desire and ability to envision, design, and fabricate the images, objects, and structures we all encounter, use, occupy, and enjoy every day of our lives.

Today, as has been the case throughout history and across cultures, there are different titles for those who make and build. An artisan or craftsperson, for example, may produce decorative or utilitarian arts, such as quilts or baskets. Often, an artisan or craftsperson is a skilled worker, but not the inventor of the original idea or form. An artisan or craftsperson can also be someone who creates their own designs, but does not work in art forms or with materials traditionally associated with the so-called Fine Arts, such as painting and sculpture. A craftsperson might instead fashion jewelry, forge iron, or blow glass into patterns and objects of their own devising. Such inventive and skilled pieces are often categorized today as Fine Craft or Craft Art.

Art is Pretentious* | The Art Assignment | PBS Digital Studios (9:25)

In many cultures throughout much of history, those who produced, embellished, painted, and built were not considered to be artists as we think of them now. They were artisans and craftspeople, and their role was to make the objects and build the structures for which they were hired, according to the design (their own or another’s) agreed upon with those for whom they were working. That is not to say they were untrained. In Medieval Europe, or the Middle Ages (fifth-fifteenth centuries), for example, an artisan generally began around the age of twelve as an apprentice, that is, a student who learned all aspects of a profession from a master who had their own workshop. Apprenticeships lasted five to nine years or more, and included learning trades ranging from painting to baking, and masonry to candle making. At the end of that period, an apprentice became a journeyman and was allowed to become a member of the craft guild that supervised training and standards for those working in that trade. To achieve full status in the guild, a journeyman had to complete their “masterpiece,” demonstrating sufficient skill and craftsmanship to be named a master.

We have little information about how artists trained in numerous other time periods and cultures, but we can gain some understanding of what it meant to be an artist by looking at examples of art work that were produced. Seated Statue of Gudea depicts the ruler of the state of Lagash in Southern Mesopotamia, today Iraq, during his reign, c. 2144-2124 BCE (Figure 1).

Gudea is known for building temples, many in the kingdom’s main city of Girsu (today Telloh, Iraq), with statues portraying himself in them. In these works, he is seated or standing with wide, staring eyes but otherwise a calm expression on his face and his hands folded in a gesture of prayer and greeting. Many of the statues, including the one pictured here, are carved from diorite, a very hard stone favored by rulers in ancient Egypt and the Near East for its rarity and the fine lines that can be cut into it. The ability to cut such precise lines allowed the craftsperson who carved this work to distinguish between and emphasize each finger in Gudea’s clasped hands as well as the circular patterns on his stylized shepherd’s hat, both of which indicate the leader’s dedication to the well-being and safety of his people.

Although the sculpture of Gudea was clearly carved by a skilled artisan, we have no record of that person, or of the vast majority of the artisans and builders who worked in the ancient world. Who they worked for and what they created are the records of their lives and artistry. Artisans were not valued for taking an original approach and setting themselves apart when creating a statue of a ruler such as Gudea: their success was based on their ability to work within standards of how the human form was depicted and specifically how a leader should look within that culture at that time. The large, almond-shaped eyes and compact, block-like shape of the figure, for example, are typical of sculpture from that period. This sculpture is not intended to be an individual likeness of Gudea; rather, it is a depiction of the characteristic features, pose, and proportions found in all art of that time and place.

Objects made out of clay were far more common in the ancient world than those made of metal or stone, such as the Seated Statue of Gudea, which were far more costly, time-consuming, and difficult to make. Human figures modeled in clay dating back as far as 29,000-25,000 BCE have been found in Europe, and the earliest known pottery, found in Jiangxi Province, China, dates to c. 18,000 BCE. Vessels made of clay and baked in ovens were first made in the Near East c. 8,000 BCE, nearly 6,000 years before the Seated Statue of Gudea was carved. Ceramic (clay hardened by heat) pots were used for storage and numerous everyday needs. They were utilitarian objects made by anonymous artisans.

Among the ancient Greeks, however, pottery rose to the level of an art form. But, the status of the individuals who created and painted the pots did not. Although their work may have been sought after, these potters and painters were still considered artisans. The origins of pottery that can be described as distinctively Greek dates to c. 1,000 BCE, in what is known as the Proto-geometric period. Over the next several hundred years, the shapes of the vessels and the types of decorative motifs and subjects painted on them became associated with the city where they were produced, and then specifically with the individuals who made and decorated the pots. The types of pots signed by the potter and the painter were generally large, elaborately decorated or otherwise specialized vessels that were used for ritual or ceremonial purposes.

That is the case with the Panathenaic Prize Amphora, 363-362 BCE, signed by Nikodemos, the potter, and attributed to the Painter of the Wedding Procession, whose name is not known but is identified through similarities to other painted pots (Figure 2). The Panathenaia was a festival held every four years in honor of Athena, the patron goddess of Athens, Greece, who is depicted on the amphora, a tall, two-handled jar with a narrow neck. On the other side of the storage jar, Nike, the goddess of victory, crowns the winner of the boxing competition for which this pot—containing precious olive oil from Athena’s sacred trees—was awarded by the city of Athens. Only the best potters and painters were hired to make pots that were part of such an important ceremony and holding such a significant prize. While the vast majority of artisans never identified themselves on their work, these noteworthy individuals were set apart and acknowledged by name. The makers’ signatures demonstrated the city’s desire to give an award of the highest quality; they acted as promotion for the potter and painter at that time, and they have immortalized them since. It must not be forgotten, however, that the prize inside the pot was considered far more important than the vessel or the skilled artisans who created it.

China was united and ruled by Mongols from the north, first under Kublai Kahn, in the period known as the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). The hand scroll painting Pear Blossoms was created with ink and colors on paper around 1280 by Qian Xuan (c. 1235-before 1307, China) (Figure 3).

After the establishment of the Mongolian government, Qian Xuan abandoned his goal of obtaining a position as a scholar-official, as the highly educated bureaucrats who governed China were known, and turned to painting. He was part of a group of artists known as scholar-painters, or literati. The work of scholar-painters was desirable to many admirers of art because it was considered more personal, expressive, and spontaneous than the uniform and realistic paintings by professional, trained artists. The scholar-painters’ sophisticated and deep knowledge of philosophy, culture, and the arts— including calligraphy—made them welcome among fellow scholars and at court. They were part of the elite class of leaders, who followed the long and noble traditions within Confucian teachings of expressing oneself with wisdom and grace, especially in the art of poetry.

Qian Xuan was one of the first scholar-painters to unite painting and poetry, as he does in Pear Blossoms:

All alone by the veranda railing, teardrops drenching the branches,

Although her face is unadorned, her old charms remain;

Behind the locked gate, on a rainy night,

how she is filled with sadness.

How differently she looked bathed in golden waves

of moonlight, before the darkness fell.

The poem is not meant to illustrate or describe his painting of the branch with its delicate, young foliage and flowers; rather, the swaying, irregular lines of the leaves and the gently unfurling curves of the blossoms are meant to suggest comparisons to how quickly time passes—delicate blooms will soon fade—and evoke memories of times past.

In thirteenth-century China, as has been the case throughout much of that country’s history, the significance of a painting is closely associated with the identity of the artist, and with the scholars and collectors who owned the work over subsequent centuries. Their identities are known by the seals, or stamps in red acting as a signature, each added to the work of art. Specific subjects and how they were depicted were associated with the artist, and often referred back to in later works by other artists as a sign of respect and acknowledgment of the earlier master’s skill and expertise. In Pear Blossoms, as was often the case, the poem, and the calligraphy in which the artist wrote it, were part of the original composition of the entire painted scroll. The seals appended and notes written by later scholars and collectors continued adding to the composition, and its beauty and meaning, over the next seven hundred years.

When James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903, USA, lived England) painted Arrangement in Flesh Colour and Black, Portrait of Theodore Duret in 1883, he was making references back to the makers’ marks Chinese and Japanese potters used as signatures on their ceramics in the monogram he adopted for his work: a stylized design of a butterfly based on his initials (Figure 4). Whistler began signing his work with the recognizable but altered figure of a butterfly, which often appeared to be dancing, in the 1860s. He had begun collecting Japanese porcelain and prints, and was tremendously influenced by their colors, patterns, and compositions, which reflected Japanese principles of beauty in art, including elegant simplicity, tranquility, subtlety, naturalness, understated beauty, and asymmetry or irregularity.

Whistler was among numerous American and European artists in the second half of the nineteenth century who felt compelled to break away from what they believed were the inhibiting constraints in how and what art students were taught and in the system of traditional art exhibitions. For Whistler and others, such restrictions were intolerable; as artists, they must be allowed to freely follow their own creative voices and pursuits. In adopting Japanese principles of beauty in art, Whistler could pursue what he called “Art for art’s sake.” That is, he could create art that served no other purpose than to express what he, as the artist, found to be elevating, harmonious, and pleasing to the eye, the mind, and the soul:

Art should be independent of all claptrap—should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like. All these have no kind of concern with it; and that is why I insist on calling my works “arrangements” and “harmonies.”[1]

Setting the artist apart in this way, as someone with special qualifications and sensibilities at odds with the prevailing cultural and intellectual standards, was far from the role played by a scholar-painter such as Qian Xuan in thirteenth-century China. The work Qian Xuan created was in accord with prevailing standards, while Whistler often thought of himself and his art as conflicting with the conventions of his day. Continuing one notion or categorization of the artist that had been present in Europe since the sixteenth century (and, later, the United States), Whistler was the singular, creative genius, whose art was often misunderstood and not necessarily accepted.

That was indeed the case. In 1878, Whistler won a lawsuit for libel against the art critic John Ruskin, who described Whistler’s 1875 painting, Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, as “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face” (Figure 5). By around 1880, in the aftermath of that rancorous proceeding, Whistler often added a long stinger to his butterfly monogram, symbolizing both the gentle beauty of his art as well as the forceful, at times stinging, nature of his personality.

Why Do We Make Art?

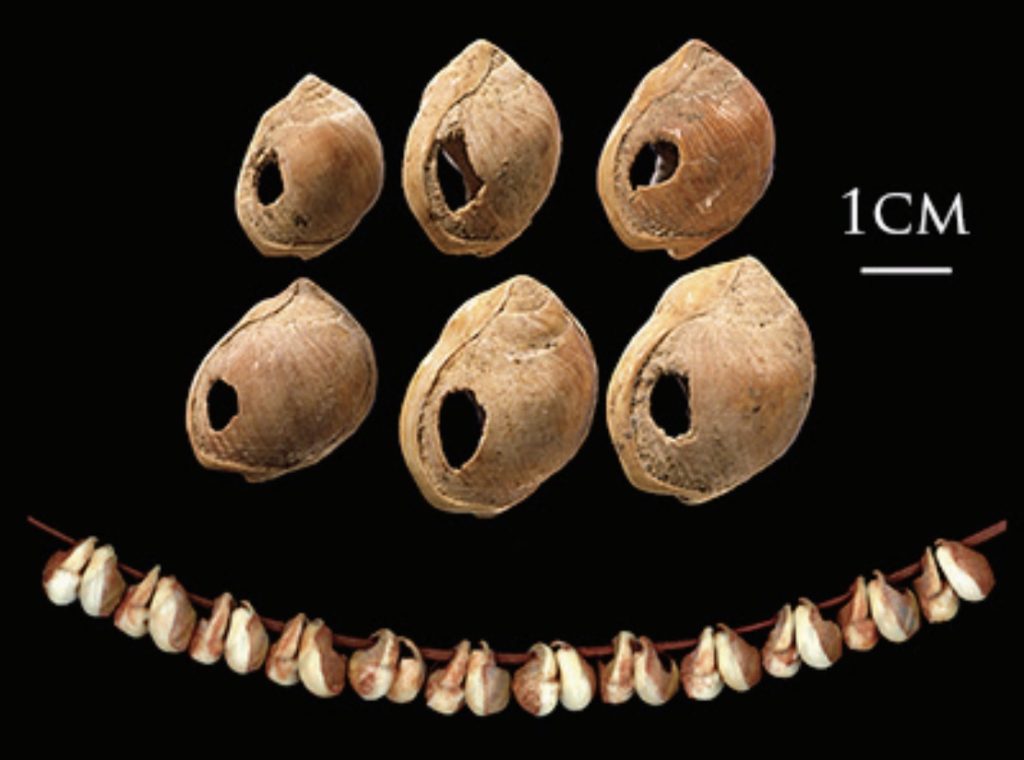

Some of the earliest evidence of recognizable human activity includes not only practical things like stone tools and fire pits, but also decorative objects used for personal adornment. For example, these small beads made by piercing sea snail shells, found at the Blombos Cave on the southeastern coast of South Africa, are dated to the Middle Stone Age, 101,000-70,000 BCE (Figure 6). We can only speculate about the intentions of our distant ancestors, but it is clear that their lives included the practice of conceiving and producing art objects. One thing we appear to share with those distant relatives is the urge to make art.

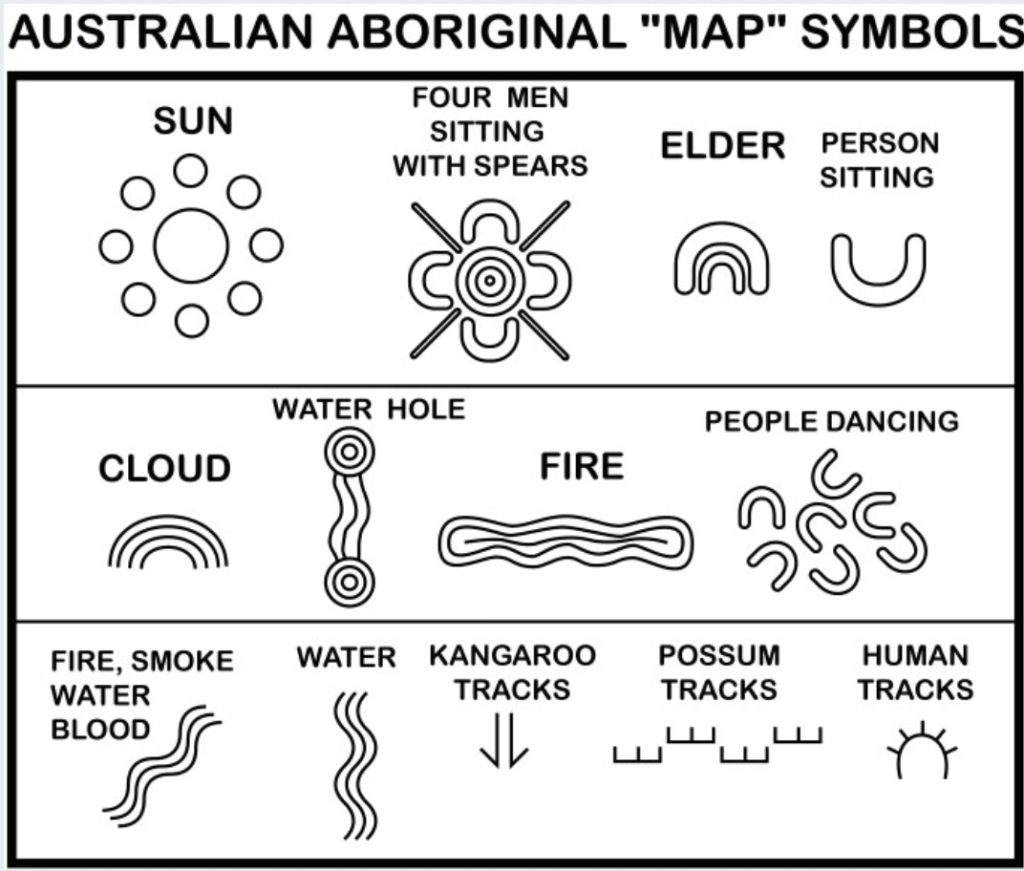

A culture can be defined as a group of people who agree about what is important. Today many different human cultures and sub-cultures co-exist; we can find in them a broad range of ideas about art and its place in daily living. One main goal of Australian Aboriginal artists, for example, is to “map” the world around them (Figure 7).

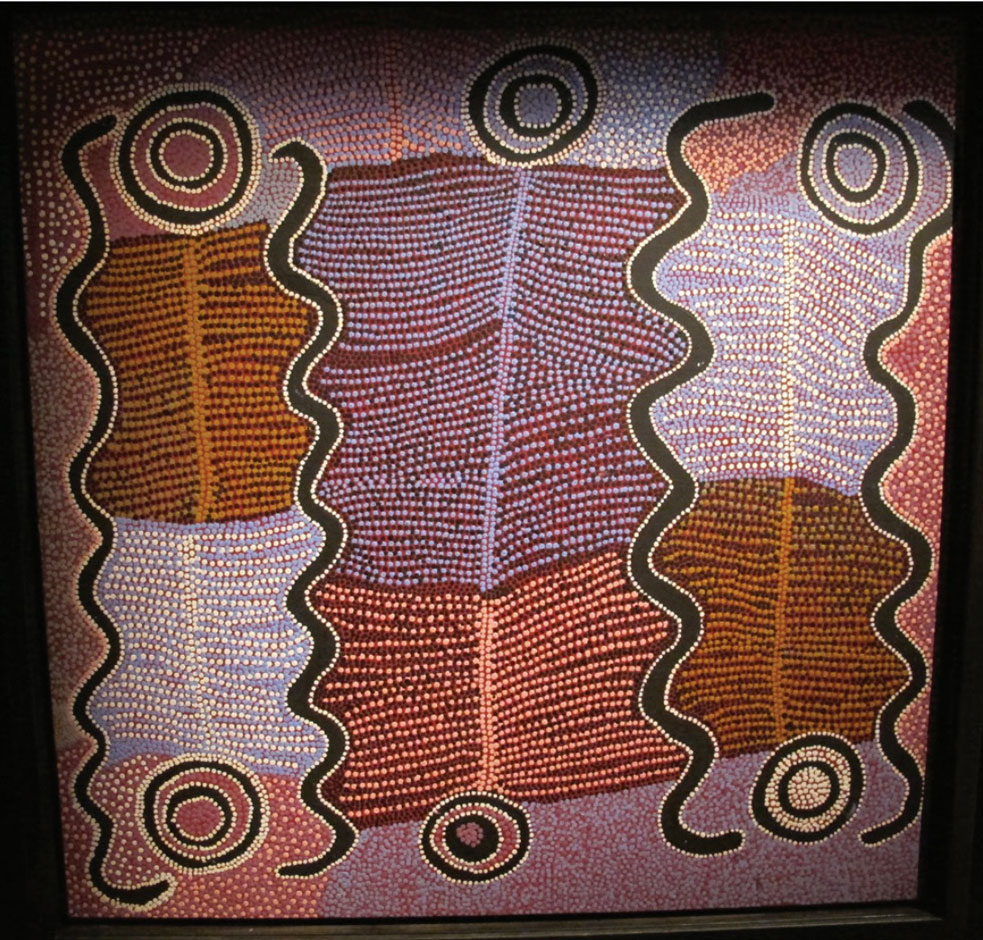

In this painting on bark, pictorial symbols tell the story of the great hunter snake in colors such as red for desert sand and yellow for the sun (Figure 8). In a similar way, though with different materials, Buddhist sand paintings known as mandalas present a map of the cosmos. These circular diagrams also represent the relationship of the individual to the whole and levels of human awareness (Figure 9).

The need to make art can be divided into two broad categories: the personal need to express ideas and feelings, and the community’s needs to assert common values. In the following sections, we’ll look at some of these motivations to more clearly understand and identify artist intent in the works of art that we encounter.

We should recognize that every person has lived a unique life, so every person knows something about the world that no one else has seen. It is the job of artists today to tell us about what they have come to know—individually or as part their community—using the art material or medium most suited to their abilities. While copying the works of others is good training, it is merely re-working what has already been revealed. Originality, however, is more highly valued in contemporary art. Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986, USA) explained her view on this matter when she wrote (Figure 10):

It was in the fall of 1915 that I first had the idea that what I had been taught was of little value to me except for the use of my materials as a language—charcoal, pencil, pen and ink, watercolor, pastel, and oil. I had become fluent with them when I was so young that they were simply another language that I handled easily. But what to say with them? I had been taught to work like others, and after careful thinking I decided that I wasn’t going to spend my life doing what had already been done. . . . I decided I was a very stupid fool for not to at last paint as I wanted to and say what I wanted to when I painted.[2]

The Personal Need to Create

Many works of art come out of a personal decision to put a feeling, idea, or concept into visual form. Since feelings vary widely, the resulting art takes a wide range of forms. This approach to art comes from the individual’s delight in the experience. Doodling comes to mind as one very basic example of such delight. Pollock’s Abstract Expressionist works, also known as action paintings, are much more than doodles, though they may resemble such on the surface (Autumn Rhythm-Number 30, Jackson Pollock; Number 10, Jackson Pollock). They were the result of many levels of artistic thought but on a basic level were a combination of delight in the act of painting and in the personal discovery that act enabled.

Some art is intended to provide personal commentary. Artworks that illustrate a personal viewpoint or experience can fulfill this purpose. Persepolis, a graphic novel by Marjane Satrapi (b. 1969, Iran) published in 2000, recounts her experiences and thoughts during the 1979 Iranian revolution, and is an example of such personal commentary (Keys to Paradise). Satrapi is a leading proponent of the graphic novel, a new approach to art making. In an ironic critique of how different parts of Iranian society were affected by war, Satrapi compares the contorted figures of Iranian youth dying in a combat zone explosion with the dance movements at her high school celebration.

Artworks can be created thus as a means of exploring one’s own experience, a way of bringing hidden emotions to the surface so that they may be recognized and understood more clearly. The term for this process is catharsis.

Cathartic works of art can arise from perceptions of grief, good, evil, or injustice, as in The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault (1791-1824, France), which was an indictment of the French government of his day following the sinking of a ship (Figure 11). When Whistler, on the other hand, became a proponent of “Art for art’s sake,” he was rejecting outside influences such as contemporary artistic and social standards in order to “purify” art of external corruption. The idea of removing influence from the creation of art is a modern one. Much of the art made before the nineteenth century was produced with the support and under the direction of religious, political, and cultural authorities in the larger community.

Communal Needs and Purposes

Across history and geography, we see religious and political communities that remain stable despite constant pressure from both internal and external sources. One way in which communities maintain stability is in the production of works of art that identify common values and experiences within that community and thus bring people together.

Architecture, monuments, murals, and icons are visible guides to community participation in the arts and often use image-making conventions. A convention is an agreed upon way of thinking, speaking, or acting in a social context. There are many kinds of conventions, including visual conventions. A good example in visual art would be a conventional sense of direction. In Western cultures, text is generally read left to right. Therefore, when they look at artwork, Western viewers tend to “enter” a picture on the upper left and proceed to the right. Objects that appear on the left side of an image are thought to be “first,” while ones that appear on the right are thought to be “later.” Since Asian texts follow a different convention, and tend to be read right to left, an Asian viewer would unconsciously assume the opposite.

Architecture, especially of public buildings, is an expression of a community’s values. Courthouses, libraries, town halls, schools, banks, factories, and jails are all designed for community purposes, and their shapes become strongly associated with their function: the architectural shapes become conventions. The use of older styles of architecture can be as references to the values of previous cultures. In the United States, for example, many government buildings are designed with imposing stone facades using classical Greek and Roman columns that symbolize strength and stability. Federal government buildings such as the United States Capitol and the Supreme Court (Figure 12) were designed so that the community would associate ancient Greek and Roman ideals of virtue and integrity with the activities inside those more modern buildings.

Many twentieth-century architects, however, have followed the guiding principle of American architect Louis Sullivan (1856-1924, USA), that “form follows function.” In his design of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius (1883-1969, Germany) rejected superfluous decoration and focused instead on the efficient and functional use of space and material (Figure 13). The leading school of art, craft, and architecture in Germany from 1919-1933, the teachings of the Bauhaus, or “construction house,” have strongly influenced domestic and industrial design internationally since that time.

Since ancient times, murals, paintings on walls, have been created in both public and private places. Ancient Egyptians combined images with writing in wall paintings to commemorate past leaders. Some of these murals were intentionally erased when the leader fell out of favor. Roman murals were more often found inside homes and temples. The Roman mural located in a bedroom of the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor was unearthed in Pompeii, Italy (Figure 17). It depicts landscape and architectural views between a row of (painted) columns, as if viewed from inside the villa, or country house.

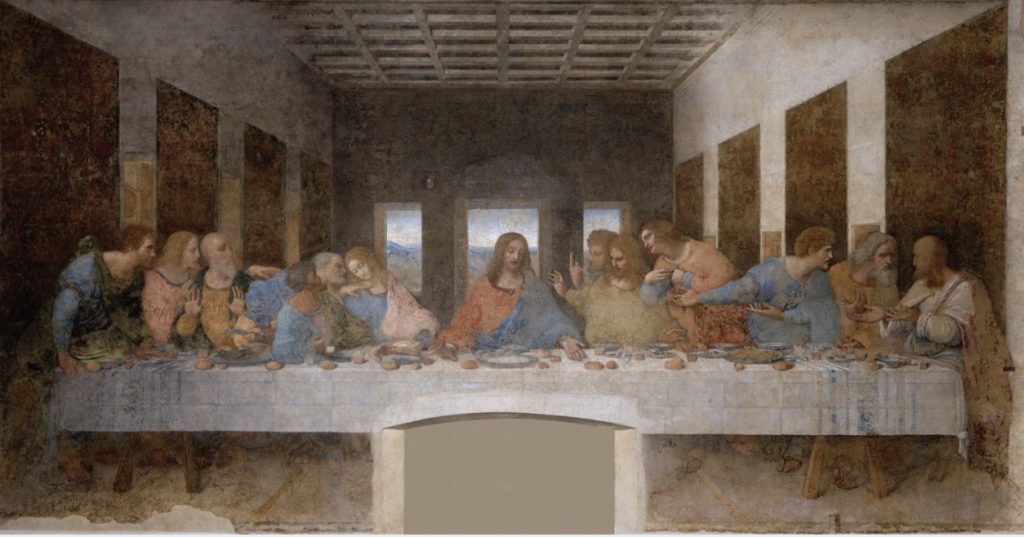

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519, Italy, France) and the Sistine Chapel ceiling by Michelangelo (1475- 1564, Italy) are murals from the Italian Renaissance. They were created for a wall in a refectory, or dining hall, of a monastery (Figure 18) and for the ceiling of the Pope’s chapel (Figure 19). Both depict crucial scenes in the teachings of the Catholic Church, the leading European religious and political organization of the time. Because many people at the time were illiterate, images played an important role in educating them about their religious history and doctrines.

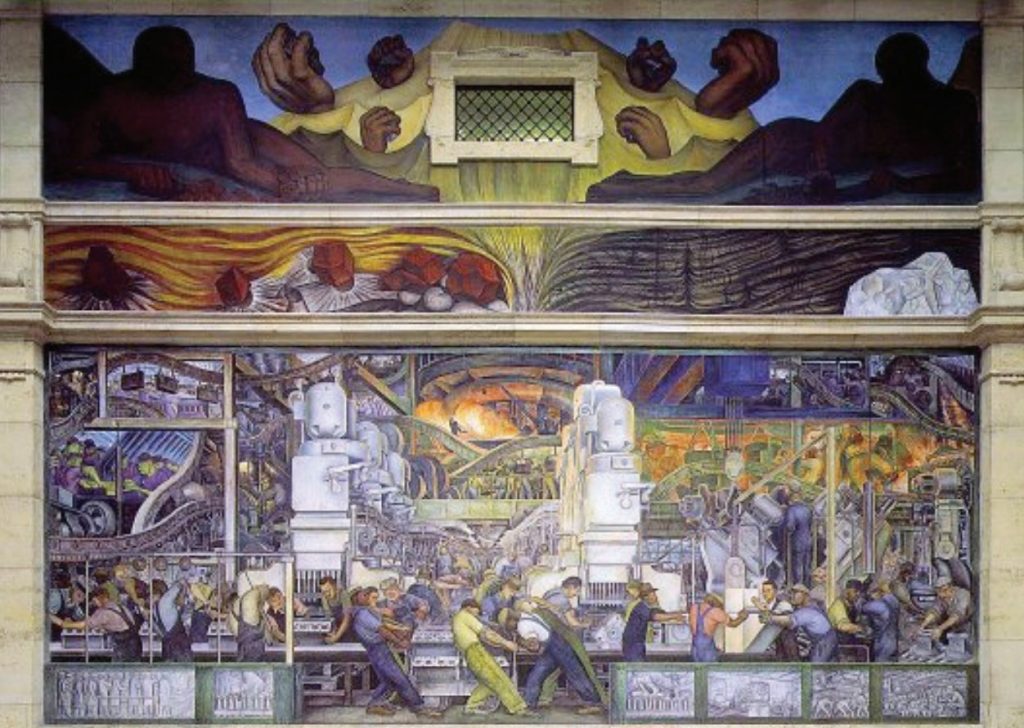

More modern examples of murals can be found around the world today. Diego Rivera (1886-1967, Mexico) was a world-renowned artist who executed large-scale murals in Mexico and the United States. His Detroit Industry murals consist of twenty-seven panels originally installed at the Detroit Institute of Arts (Figure 20). The two largest panels depict workers manufacturing a V8 engine at the Ford Motor Company factory. Other smaller panels show advances in science, technology, and medicine involved in modern industrial culture, portraying Rivera’s belief that conceptual thinking and physical labor are interdependent. These works are now considered a National Landmark. The Great Wall of Los Angeles designed by Judith Baca (b. 1946, USA) and executed by hundreds of community members is thirteen feet high and runs for more than one half mile through the city. (The Great Wall of Los Angeles, Judith Baca). Its subject is the history of Southern California “as seen through the eyes of women and minorities.”[3] The mural is part of a larger push in Los Angeles to adorn public spaces with murals that inform and educate the populace.

The term icon comes from the Greek word eikon, or “to be like,” and refers to an image or likeness that is used as a guide to religious worship. The holy figures depicted in icons are thought by believers to have special powers of healing or other positive influence. An icon can also be a person or thing that symbolically represents a quality or virtue. A good example is the image of St. Sebastian. St. Sebastian was a captain of the Roman guard who converted to Christianity and was sentenced to death before a squad of archers (Figure 21). He survived his wounds, and early Christians attributed this miracle to the power of their religion. (He was later stoned to death.) In the late Middle Ages during widespread plague in Europe, images of St. Sebastian were regularly commissioned for hospitals because of the legend of his miraculous healing and the hope that the images would be curative.

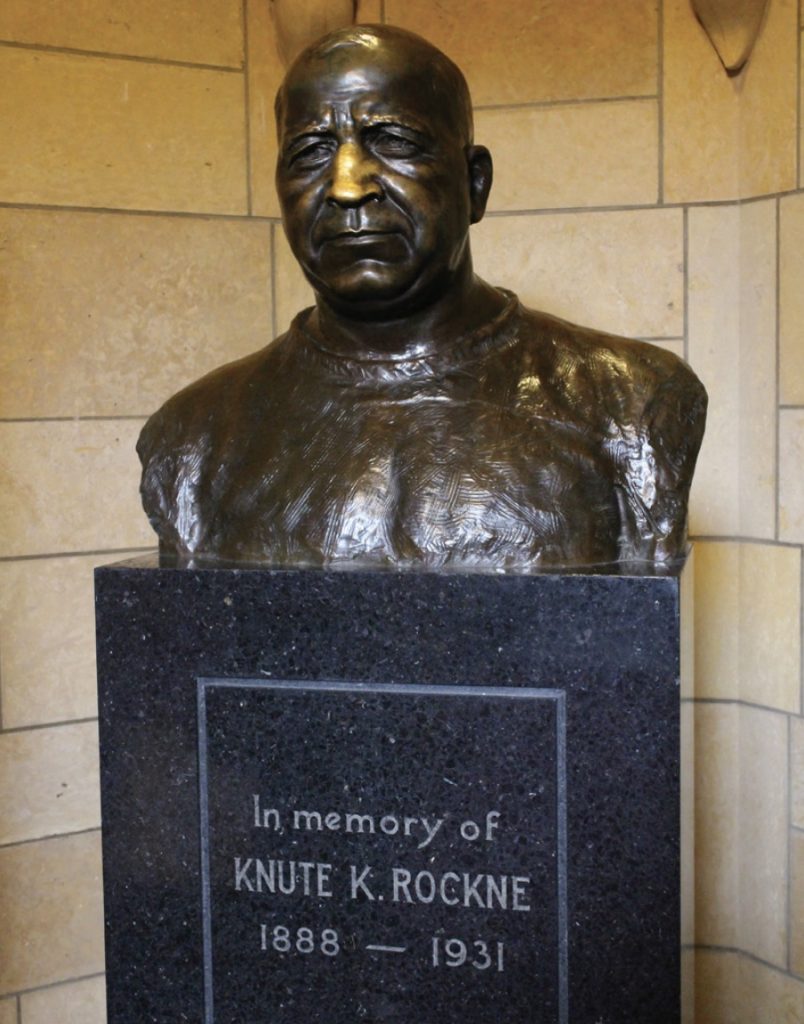

An example of a non-religious or secular icon might be the bronze bust of the famous football coach Knute Rockne at Notre Dame University in Indiana (Figure 22). The nose of the bronze sculpture is bright gold because many consider it good luck to rub it, so it receives constant polishing by students before exams.

We have touched only briefly on the questions of what art is, who an artist is, and why people make art. History shows us people have defined art and artists differently in various times and places, but that people everywhere make art for many different reasons. And, these art objects share a common purpose: they are all intended to express a feeling or idea that is valued either by the individual artist or by the larger community.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Gudea © Source: Met Museum; License: OASC

- Figure 2. Panathenaic Prize Amphora with Lid © Artist: Nikodemos; Source: The J. Paul Getty Museum. Open Content.

- Figure 3. Pear Blossoms © Artist: Qian Xuan; Source: Met Museum; License: OASC

- Figure 4. Arrangement in Flesh Colour and Black: Portrait of Theodore Duret © Artist: James Abbott McNeill Whistler; Source: Met Museum; License: OASC

- Figure 5. Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket © Artist: James Abbott McNeill Whistler; Source: Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 6. Blombos Cave Nassarius kraussianus marine shell beads and reconstruction of bead stringing is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7. Australian Aboriginal “Map” Symbols © Jeffrey LeMieux is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 8. Sand Painting is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 9. Wheel of Time Kalachakra Sand Mandala is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 10. Series 1, No. 8 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 11. The Raft of Medusa is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 12. U.S. Supreme Court Building is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 13. The Bauhaus Building in Dessau, Germany is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 14. Colleoni on Horseback is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 15. Burghers of Calais is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 16. Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 17. Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale

- Figure 18. The Last Supper is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 19. The Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 20. Detroit Industry, North Wall is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 21. The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 22. Knute Rockne is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Art: Design, Context, and Meaning. Authored by: Sachant, Pamela; Blood, Peggy; LeMieux, Jeffery; and Tekippe, Rita. Retrieved from: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=arts-textbooks. Project: Fine Arts Open Textbooks. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike