Chapter 8.6: Ancient Rome

From a Republic to an Empire

Legend has it that Rome was founded in 753 B.C.E. by Romulus, its first king. In 509 B.C.E., Rome became a republic ruled by the Senate (wealthy landowners and elders) and the Roman people. During the 450 years of the republic, Rome conquered the rest of Italy and then expanded into France, Spain, Turkey, North Africa, and Greece.

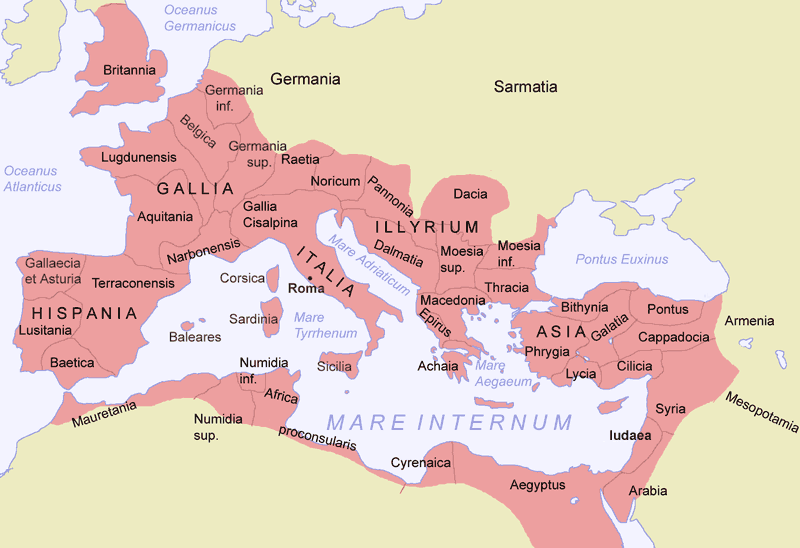

Rome became very Greek-influenced or “Hellenized,” and the city was filled with Greek architecture, literature, statues, wall paintings, mosaics, pottery, and glass. But with Greek culture came Greek gold, and generals and senators fought over this new wealth. The Republic collapsed in civil war, and the Roman empire began, and the emperor became the focus of the empire and its people. By the time of the emperor Trajan, in the late first century C.E., the Roman empire, with about fifty million inhabitants, encompassed the whole of the Mediterranean, Britain, much of northern and central Europe, and the Near East.

Ancient Roman Art

Roman art is a very broad topic, spanning almost 1,000 years and three continents, from Europe into Africa and Asia. The first Roman art can be dated back to 509 B.C.E., with the legendary founding of the Roman Republic, and lasted until 330 C.E. (or much longer, if you include Byzantine art). Roman art also encompasses a broad spectrum of media including marble, painting, mosaic, gems, silver and bronze work, and terracottas, just to name a few.

The city of Rome was a melting pot, and the Romans had no qualms about adapting artistic influences from the other Mediterranean cultures that surrounded and preceded them. For this reason, it is common to see Greek, Etruscan, and Egyptian influences throughout Roman art. This is not to say that all of Roman art is derivative, though, and one of the challenges for specialists is to define what is “Roman” about Roman art.

Greek art certainly had a powerful influence on Roman practice; the Roman poet Horace famously said that “Greece, the captive, took her savage victor captive,” meaning that Rome (though it conquered Greece) adapted much of Greece’s cultural and artistic heritage (as well as importing many of its most famous works). It is also true that many Romans commissioned versions of famous Greek works from earlier centuries; this is why we often have marble versions of lost Greek bronzes such as the Doryphoros by Polykleitos.

The Romans did not believe, as we do today, that to have a copy of an artwork was of any less value that to have the original. The copies, however, were more often variations rather than direct copies, and they had small changes made to them, often adding humor.

Republican Rome

During the Republican period, the Romans were governed by annually elected magistrates, the two consuls being the most important among them, and the Senate, which was the ruling body of the state.

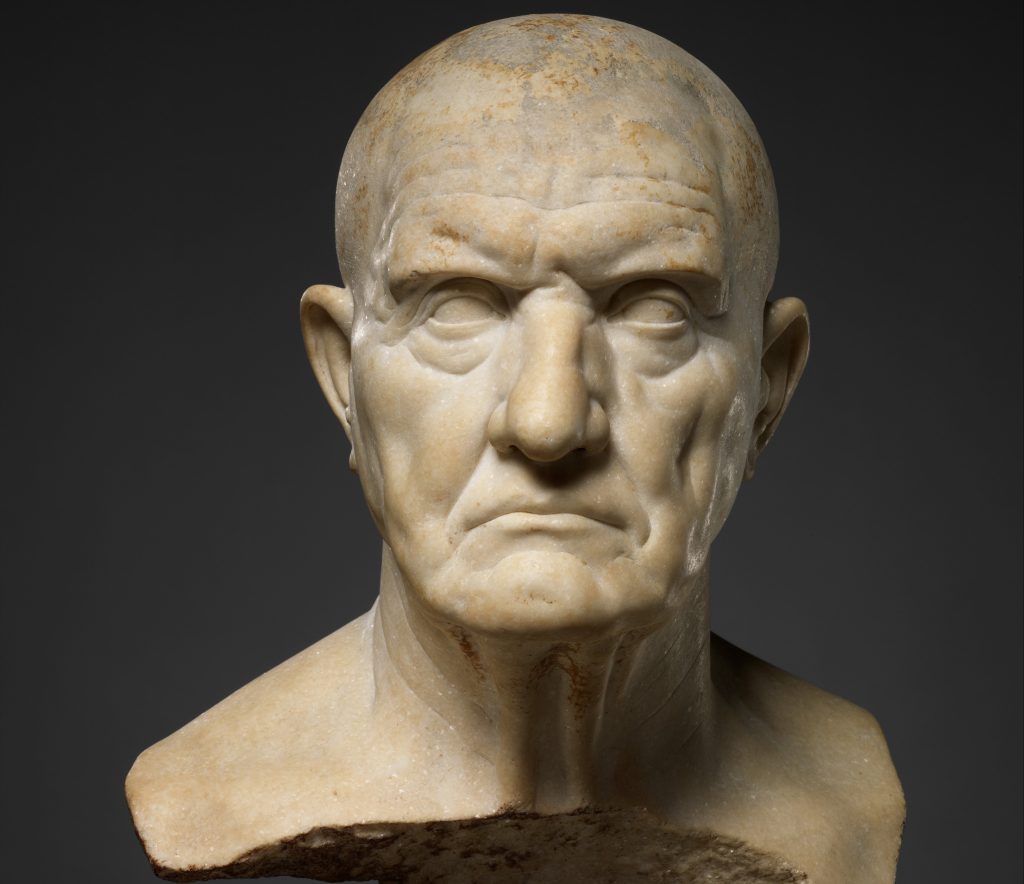

In the Republican period, art was produced in the service of the state, depicting public sacrifices or celebrating victorious military campaigns (like the Monument of Aemilius Paullus at Delphi). Portraiture extolled the communal goals of the Republic; hard work, age, wisdom, being a community leader and soldier. Patrons chose to have themselves represented with balding heads, large noses, and extra wrinkles, demonstrating that they had spent their lives working for the Republic as model citizens, flaunting their acquired wisdom with each furrow of the brow. We now call this portrait style veristic, referring to the hyper-naturalistic features that emphasize every flaw, creating portraits of individuals with personality and essence.

Image and Video

Veristic Male Portrait (2:58)

Imperial Rome

Augustus’s rise to power in Rome signaled the end of the Roman Republic and the formation of Imperial rule. Roman art was now put to the service of aggrandizing the ruler and his family. It was also meant to indicate shifts in leadership. Imperial art often hearkened back to the Classical art of the past. “Classical”, or “Classicizing,” when used in reference to Roman art refers broadly to the influences of Greek art from the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Classicizing elements include the smooth lines, elegant drapery, idealized nude bodies, highly naturalistic forms and balanced proportions that the Greeks had perfected over centuries of practice.

Augustus and the Julio-Claudian dynasty were particularly fond of adapting Classical elements into their art. The Augustus of Primaporta was made at the end of Augustus’s life, yet he is represented as youthful, idealized and strikingly handsome like a young athlete; all hallmarks of Classical art.

Image and Video

Augustus of Primaporta (4:53)

Who made Roman art?

We don’t know much about who made Roman art. Artists certainly existed in antiquity but we know very little about them, especially during the Roman period, because of a lack of documentary evidence such as contracts or letters. What evidence we do have, such as Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, pays little attention to contemporary artists and often focuses more on the Greek artists of the past. As a result, scholars do not refer to specific artists but consider them generally, as a largely anonymous group.

What did they make?

Roman art encompasses private art made for Roman homes as well as art in the public sphere. The elite Roman home provided an opportunity for the owner to display his wealth, taste and education to his visitors, dependents, and clients. Since Roman homes were regularly visited and were meant to be viewed, their decoration was of the utmost importance. Wall paintings, mosaics, and sculptural displays were all incorporated seamlessly with small luxury items such as bronze figurines and silver bowls.

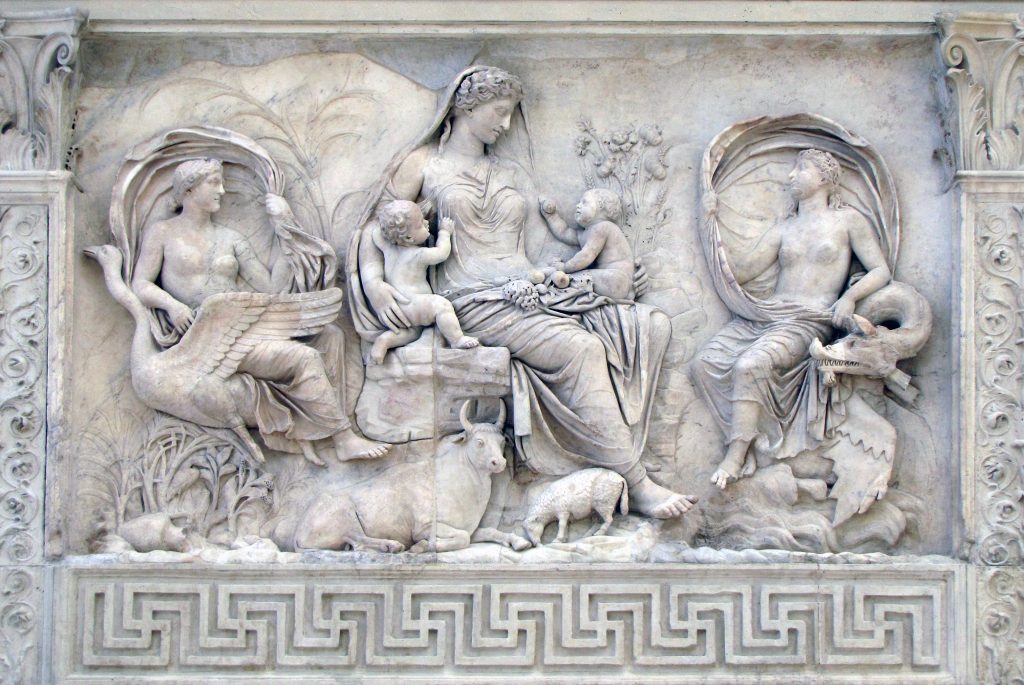

The subject matter ranged from busts of important ancestors to mythological and historical scenes, still liefs, and landscapes—all to create the idea of an erudite patron steeped in culture. The public sphere is filled with works commissioned by the emperors such as portraits of the imperial family or bath houses decorated with copies of important Classical statues. There are also commemorative works like the triumphal arches and columns that served a didactic as well as a celebratory function. The arches and columns (like the Arch of Titus or the Column of Trajan), marked victories, depicted war, and described military life. They also revealed foreign lands and enemies of the state. They could also depict an emperor’s successes in domestic and foreign policy rather than in war, such as Trajan’s Arch in Benevento.

Religious art is also included in this category, such as the cult statues placed in Roman temples that stood in for the deities they represented, like Venus or Jupiter. Gods and religions from other parts of the empire also made their way to Rome’s capital including the Egyptian goddess Isis, the Persian god Mithras and ultimately Christianity. Each of these religions brought its own unique sets of imagery to inform proper worship and instruct their sect’s followers.

It can be difficult to pinpoint just what is Roman about Roman art, but it is the ability to adapt, to take in and to uniquely combine influences over centuries of practice that made Roman art distinct.

Videos

We close our look at Roman art, enjoying two of the most important and well-known buildings left for us to wander through (the Pantheon and Colosseum).

The Column of Trajan (8:27)

Visualizing Imperial Rome (13:47)

The Pantheon and the Colosseum (8:32)

The Pantheon The Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheater) (8:34)

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Cameo with double portrait of the emperor Trajan and his wife Plotina, c. 105-115 C.E. (Image source: © Trustees of the British Museum via SmartHistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 2. Map of the Roman Empire during the reign of Emperor Trajan (Image source: SmartHistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 3. Roman Forum, view from the southwest, with (left to right) the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, Arch of Septimius Severus, and Temple of Saturn. from ca. 6th century BCE to early 7th century CE (mainly 1st century BCE-4th century CE) (Rome, Italy; Image source: University of Delaware, via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 4. Doryphoros Roman copy, c. 450-440 B.C.E., marble (Image source: University of California, San Diego, via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 5. Marble bust of a man, mid-1st century A.D. (Image source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 6. Ara Pacis Augustae, The Alter of Augustan Peace, East Front, First contructed between 13 and 9 B.C. (Rome, Italy; Image source: Steven Zucker via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7. Augustus of Primaporta, 1st century C.E. (Vatican Museums; Image source: Steven Zucker, via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 8. Painted Garden, removed from the triclinium (dining room) in the Villa of Livia Drusilla, Prima Porta, fresco, 30-20 B.C.E. (Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo, Rome; Image source: Steven Zucker via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 9. Column of Trajan, Carrera marble, completed 113 C.E., Rome, dedicated to Emperor Trajan in honor of his victory over Dacia (now Romania) (Image source: Tim Robinson via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Ancient Rome. Authored by: The British Museum. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-ancient-rome/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Introduction to Ancient Rome. Authored by: Dr. Jessica Leay Ambler. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-ancient-roman-art/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike