Chapter 7.2: Photography

The word “photograph” is based on the Greek “phos,” meaning light, and “graphe,” meaning drawing, together meaning drawing with light. Essentially, a photograph is created when a light-sensitive surface is exposed to light, leaving a mark on the surface. Camera photography was invented in the first decades of the 19th century, and even at this early point, it was able to capture more information, and with greater speed, than painting or sculpture.

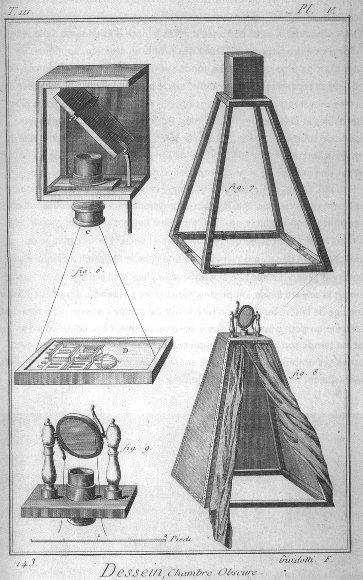

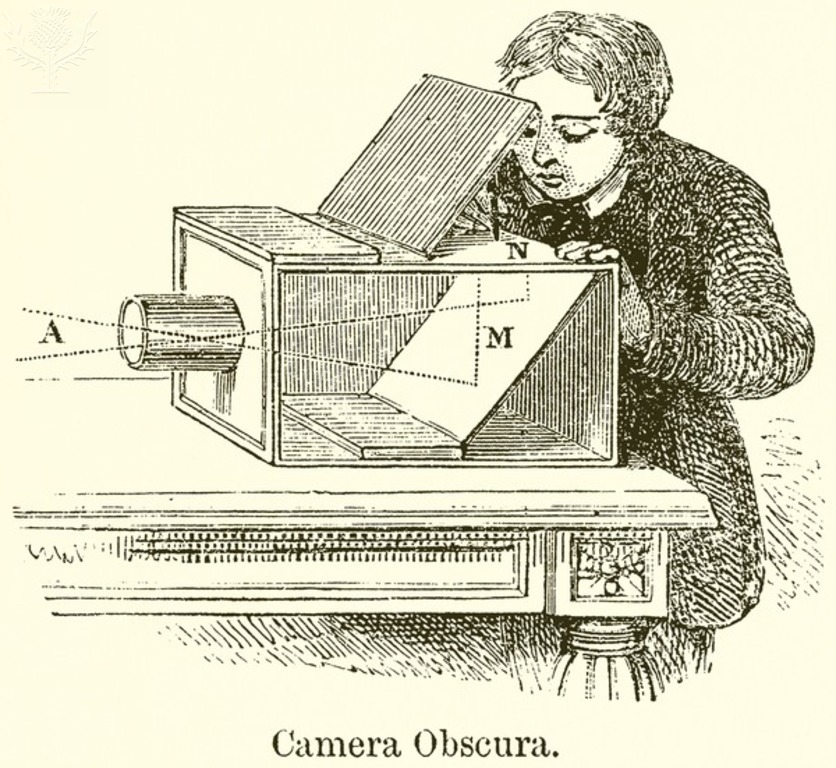

There are a number of important precursors to photography. In the 5th century BCE, before the first camera was ever invented, Chinese and Greek philosophers described the “pinhole camera,” a lightproof box with a tiny hole in one side that allowed light to pass through and project an inverted image on one side -an invention termed camera obscura in the Renaissance. In studying photography, we will be joined by the experts at the George Eastman House and the wealth of knowledge they can share about this medium.

The camera obscura was often used as a tool by artists such as Leonardo Da Vinci as a technique to create paintings.

The first commercially successful photographic process was announced in 1839, the result of over a decade of experimentation by Louis Daguerre and Nicéphore Niépce. Unfortunately, Niépce died before the daguerreotype process was realized, and is best known for his invention of the heliograph, the process by which the “first photograph” was made in 1826. The daguerreotype is a sharply defined, highly reflective, one-of-a-kind photograph on silver-coated copper plate, usually packaged behind glass and kept in a protective case.

Videos

In the videos below, you can take a look at some of the inventions that were precursors of photography, like the camera obscura, the daguerreotype, and others.

Before Photography – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 1 of 12 (6:22)

The Daguerreotype – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 2 of 12 (6:18)

The Earliest Photography

The earliest photography consisted of monochromatic or black-and-white shots. Even after color photography was invented, black and white photography still prevailed due to its lower cost and preferable appearance. During the mid-19th century, many scientists and inventors began working on the development of photography.

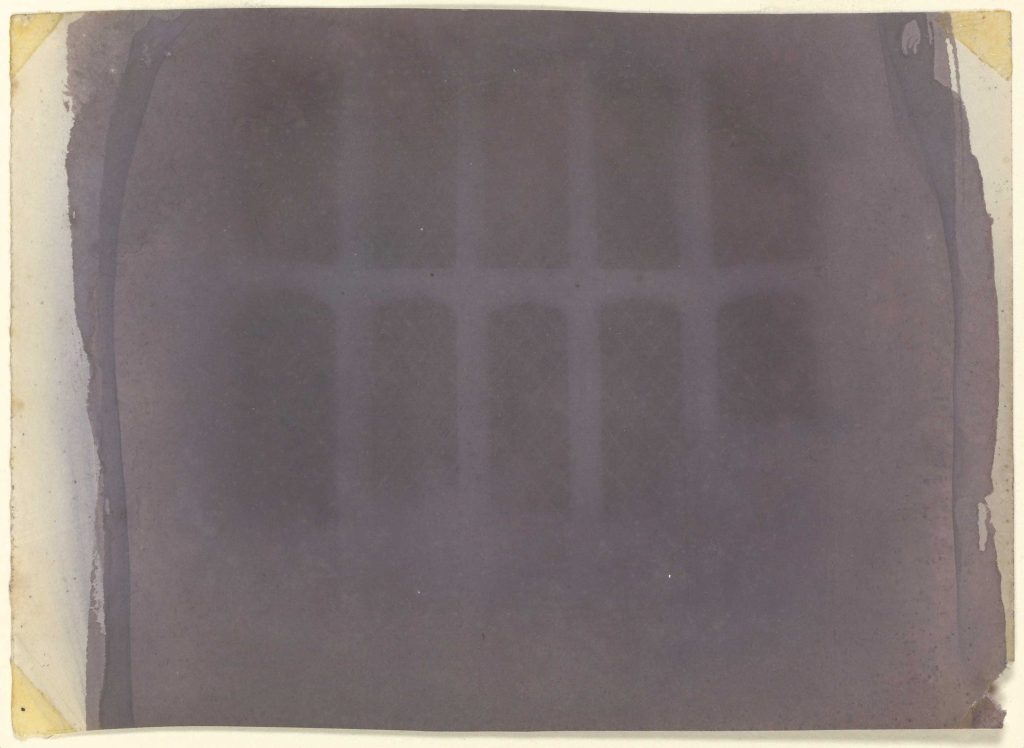

Working in England, at the same time as Daguerre, William Henry Fox Talbot is best known for the invention of the negative/positive photographic process that became the standard way of making photographs in the 19th and 20th centuries. His early processes of the photogenic drawing, salted paper print and calotype negative are demonstrated in this chapter. William Fox Talbot worked to refine Daguerre’s process in order to make the new photographic medium more available to the masses. He also invented the calotype process, which produces a paper print from a negative image. His negative of the Oriel window in Lacock Abbey is the oldest negative in existence. View Talbott’s Processes below.

The Collodion Process

Introduced in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer, the wet collodion process was a fairly simple, if somewhat cumbersome, photographic process. The collodion process replaced the daguerreotype as the predominant photographic process by the end of the 1850’s.

John Herschel was an important figure in the development of photography. He is credited with creating the first glass negative and was among the first to use the terms photography, negative, and positive. In addition, he discovered a solution that could be used to “fix” photographs in order to make them more permanent.

Videos

In the videos below, you can see Talbot’s processes and the collodion process.

Talbot’s Processes – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 3 of 12 (6:37)

The Collodion – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 5 of 12 (5:33)

Albumen Silver Print

The albumen silver print, invented in 1850, was the most popular photographic printing process of the 19th century. To make albumen silver prints, a sheet of paper is coated with albumen (egg white) and salts, then sensitized with a solution of silver nitrate. The paper is exposed in contact with a negative and printed out, which means that the image is created solely by the action of light on the sensitized paper without any chemical development.

Because the paper is coated with albumen, the silver image is suspended on the surface of the paper rather than absorbed into the paper fibers. The result is a sharp image with fine detail on a smooth, glossy surface. This is an albumen silver print shown below.

Woodburytypes

Woodburytypes are distinguished from other photomechanical processes by the fact that they are continuous-tone images. The process involves exposing unpigmented bichromated gelatin in contact with a negative. The gelatin hardens in proportion to the amount of light received. When the gelatin is washed, the unexposed portion dissolves, leaving behind a relief of the image. Under extremely high pressure, this relief is pressed into a sheet of soft lead, producing a mold of the image. This mold is then filled with pigmented gelatin and transferred to paper during printing. The process was invented in 1864 by Walter Woodbury and achieved acclaim for its exquisite rendering of pictorial detail and its permanency. Check out the fascinating process of the Woodburytypes.

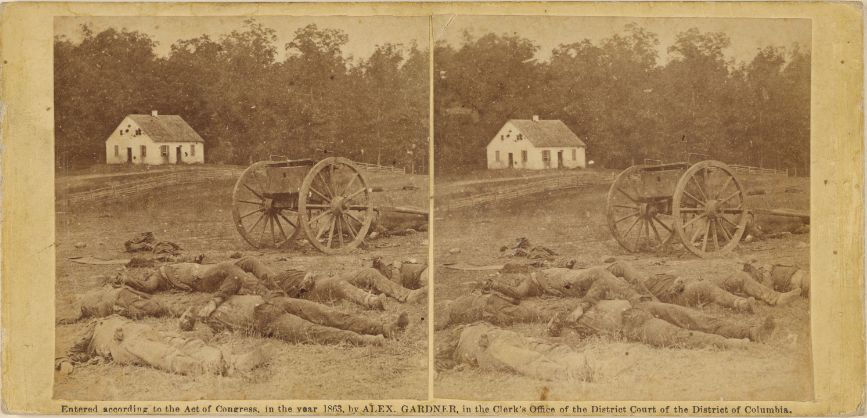

The 1860s were a defining decade for photography. In addition to the American Civil War (1861–65), the first war in American history to be documented with photographs, the 1860s also brought photography to the middle class. While the first half of the century introduced expensive daguerreotypes, the latter half of the century is defined by the development of cheaper photographic techniques. For example, the ambrotype mimicked the look of the daguerreotype with its reflective surface; however, the newer technology used a light-sensitized glass surface instead of copper, which made for a much cheaper photograph to produce and purchase. Likewise, the tintype eclipsed the ambrotype later in the decade by replacing glass with tin, an even cheaper material, and one that dried much quicker than glass. However, it was the albumen print, paper positives that retained the image quality of metal surfaces, that proved to be the winning technology, lasting well into the 20th century.

Since the earliest photographic developments, many scientists and artists have taken great interest in photography’s inherent abilities. Photography represents the first instance of an artistic medium being used widely by the masses as a mode of visual expression.

Videos

The videos below show you the photographic processes for the albumen print and the Woodburytype.

The Albumen Print – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 6 of 12 (4:33)

The Woodburytype – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 9 of 12 (3:35)

Gelatin Silver Process

The gelatin silver process was introduced at the end of the nineteenth century and dominated black-and-white photography in the twentieth century. The paper or film used to make gelatin silver prints and negatives is coated with an emulsion that contains gelatin and silver salts. Gelatin silver prints and negatives are developed out rather than printed out, which means that exposure to light registers a latent image that becomes visible only when developed in a chemical bath. This process requires shorter printing times than earlier printed-out processes such as salted paper prints and albumen prints. George Eastman’s introduction of flexible roll film and the Brownie camera revolutionized photographic practice and industry, putting photography into the hands of the masses for the first time. This process is responsible for all the black-and-white, color, and motion pictures produced in the 20th century with analog materials.

Video

The following video is a visual introduction to the gelatin silver process.

The Gelatin Silver Process – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 10 of 12 (7.:31)

An Introduction to Photography in the Early 20th Century

Photography undergoes extraordinary changes in the early part of the twentieth century. This can be said of every other type of visual representation, however, but unique to photography is the transformed perception of the medium. In order to understand this change in perception and use—why photography appealed to artists by the early 1900s, and how it was incorporated into artistic practices by the 1920s—we need to start by looking back.

In the later nineteenth century, photography spread in popularity, and inventions like the Kodak #1 camera (1888) made it accessible to the upper-middle class consumer; the Kodak Brownie camera, which cost far less, reached the middle class by 1900.

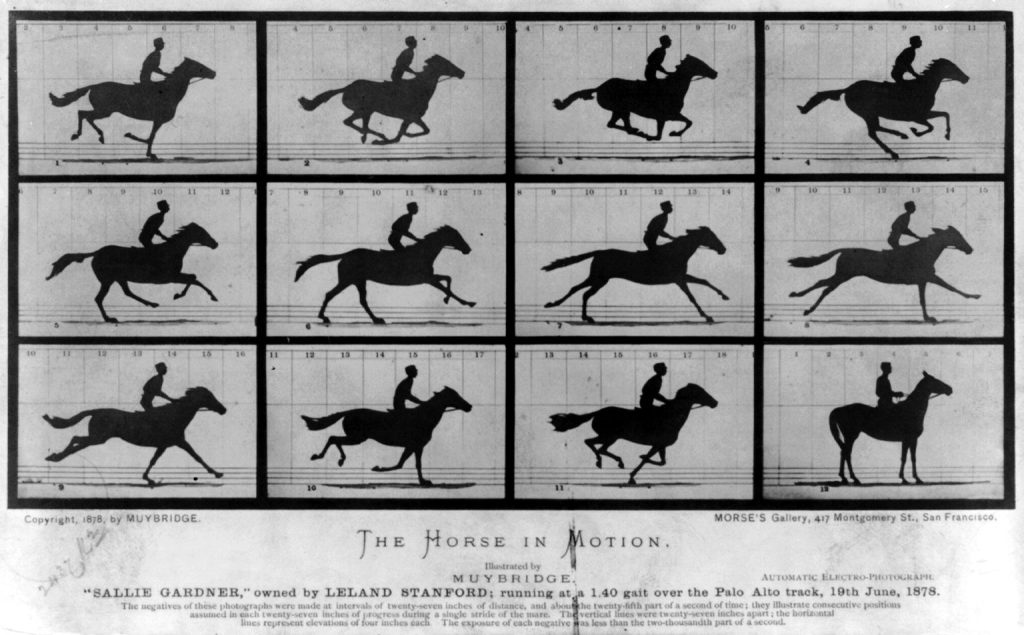

In the sciences (and pseudo-sciences), photographs gained credibility as objective evidence because they could document people, places, and events. Photographers like Eadweard Muybridge created portfolios of photographs to measure human and animal locomotion. His celebrated images recorded incremental stages of movement too rapid for the human eye to observe, and his work fulfilled the camera’s promise to enhance, or even create new forms of scientific study.

In the arts, the medium was valued for its replication of exact details and for its reproduction of artworks for publication. However, photographers struggled for artistic recognition throughout the century. It was not until Paris’s Universal Exposition of 1859, twenty years after the invention of the medium, that photography and “art” (painting, engraving, and sculpture) were displayed next to one another for the first time; separate entrances to each exhibition space, however, preserved a physical and symbolic distinction between the two groups. After all, photographs are mechanically reproduced images: Kodak’s marketing strategy (“You press the button, we do the rest”) points directly to the “effortlessness” of the medium.

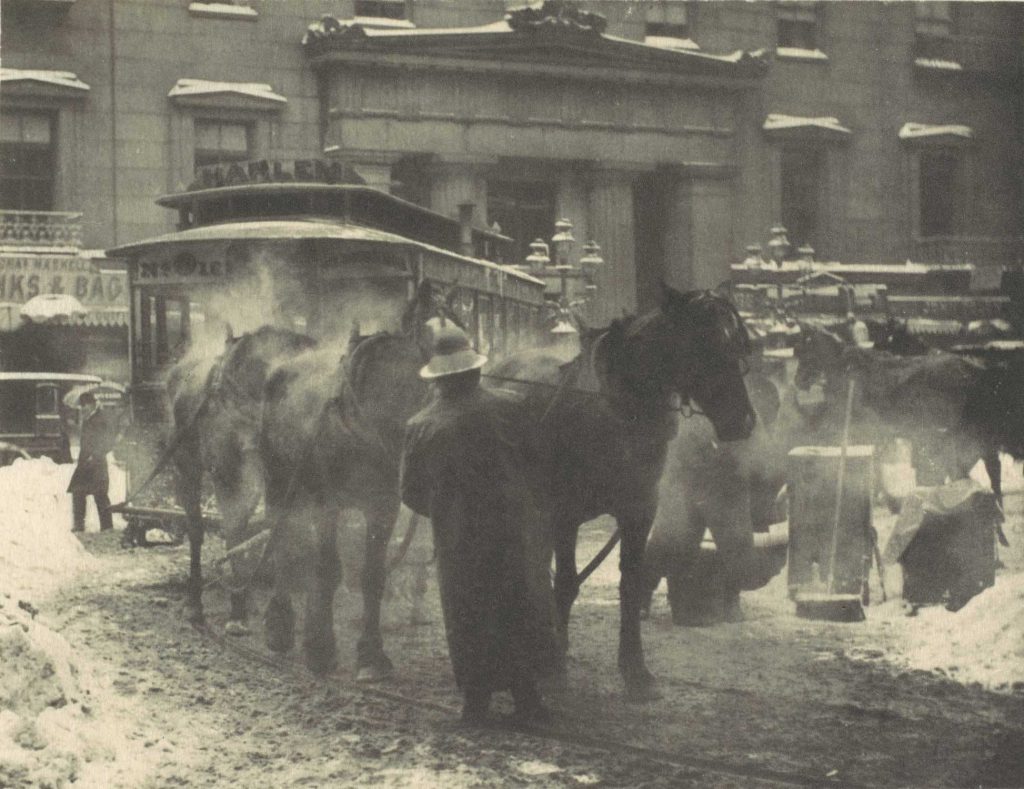

Since art was deemed the product of imagination, skill, and craft, how could a photograph (made with an instrument and light-sensitive chemicals instead of brush and paint) ever be considered its equivalent? And if its purpose was to reproduce details precisely and from nature, how could photographs be acceptable if negatives were “manipulated” or if photographs were retouched? Because of these questions, amateur photographers formed casual groups and official societies to challenge such conceptions of the medium. They—along with elite art world figures like Alfred Stieglitz—promoted the late nineteenth-century style of “art photography” and produced low-contrast, warm-toned images like The Terminal that highlighted the medium’s potential for originality.

So what transforms the perception of photography in the early twentieth century? Social and cultural change—on a massive, unprecedented scale. Like everyone else, artists were radically affected by industrialization, political revolution, trench warfare, airplanes, talking motion pictures, radios, automobiles, and much more—and they wanted to create art that was as radical and “new” as modern life itself.

By the early 1920s, technology becomes a vehicle of progress and change, and instills hope in many after the devastations of World War I. For avant-garde (“ahead of the crowd”) artists, photography becomes incredibly appealing for its associations with technology, the everyday, and science—precisely the reasons it was denigrated a half-century earlier. The camera’s mechanical reproduction technology made it the fastest, most modern, and arguably, the most relevant form of visual representation in the post-WWI era. Photography, then, seemed to offer more than a new method of image-making—it offered the chance to change paradigms of vision and representation.

With August Sander’s portraits such as Disabled Ex-Seviceman, Pastry Chef, or Secretary at a West German Radio, Cologne, we see an artist attempting to document, systematically, modern types of people as a means to understand changing notions of class and race, profession, ethnicity, and other constructs of identity. Sander transforms the practice of portraiture with these sensational, arresting images. These figures reveal as much about the German professions as they do about self-image.

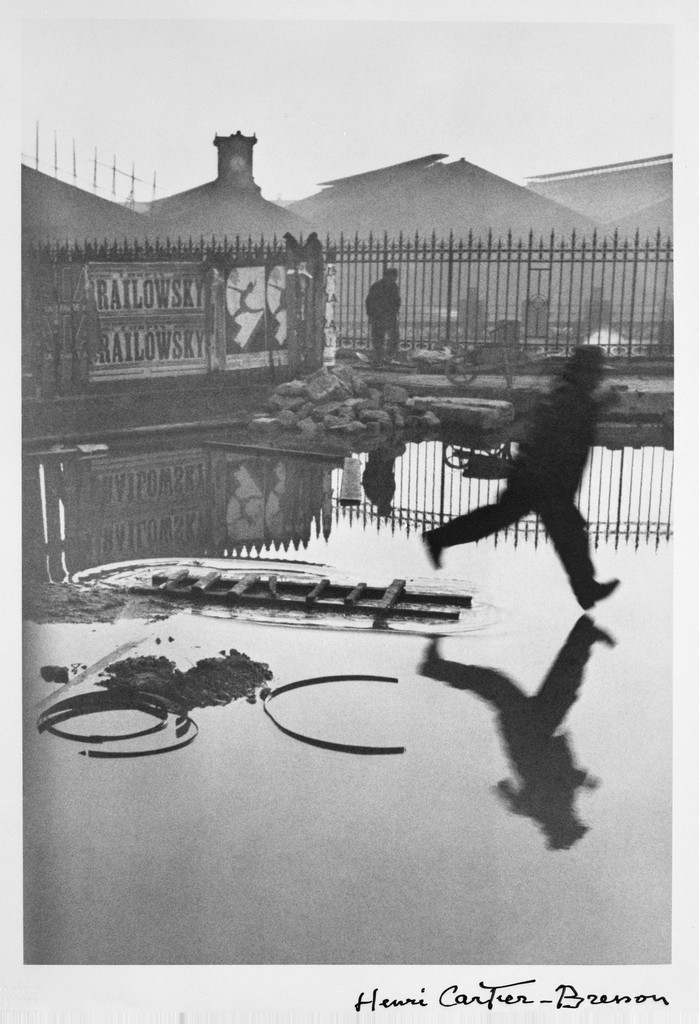

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s leaping figure in Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare reflects the potential for photography to capture individual moments in time—to freeze them, hold them, and recreate them. Because of his approach, Cartier-Bresson is often considered a pioneer of photojournalism. This sense of spontaneity, accuracy, and ephemerality corresponded to the racing tempo of modern culture (think of factories, cars, trains, and the rapid pace of people in growing urban centers).

Photography’s earliest practitioners dreamed of finding a method for reproducing the world around them in color. Some 19th-century photographers experimented with chemical formulations aimed at producing color images by direct exposure, while others applied paints and powders to the surfaces of monochrome prints. Vigorous experimentation led to several early color processes, some of which were even patented, but the methods were often impractical, cumbersome, and unreliable.

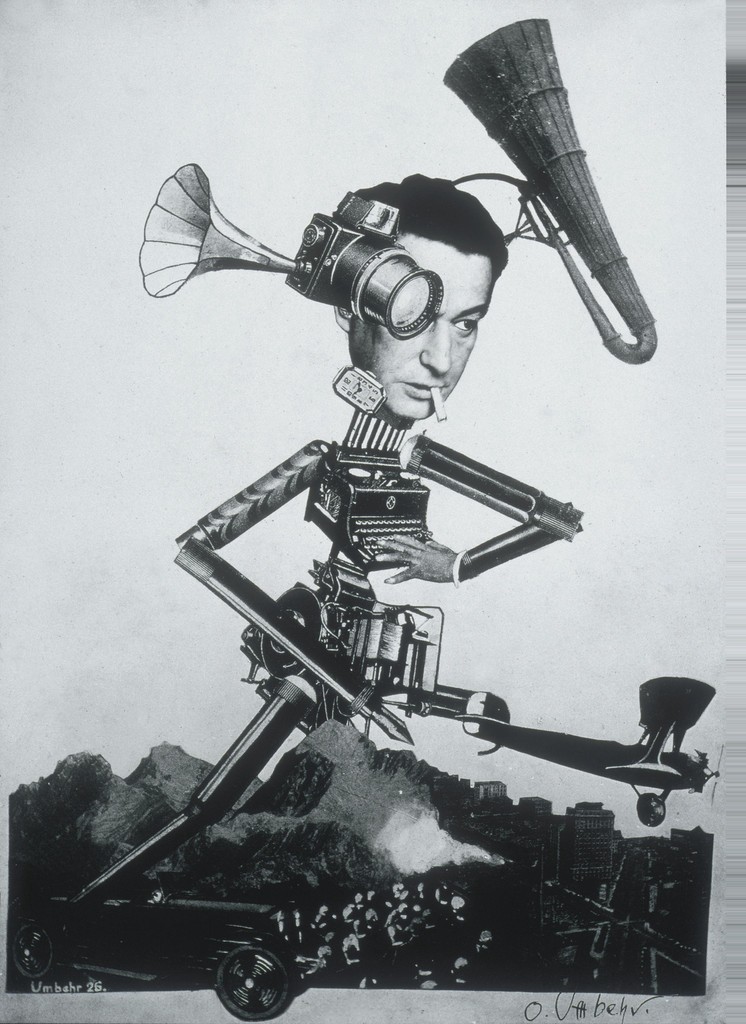

Umbo’s photomontage, The Racing Reporter, shows how modern technologies transform our perception of the world—and our ability to communicate within it. His camera-eyed, colossal observer (a real-life journalist named Egon Erwin Kisch) demonstrates photography’s ability to alter and enhance the senses. In the early twentieth century, this medium offered a potentially transformative vision for artists, who sought new ways to see, represent, and understand the rapidly changing world around them.

Eventually, Kodak engineer Steven Sasson invented the digital camera in 1975. Within 25 years the technology would overtake analog film materials and dominate the photographic industry and practice.

Videos

The Color Photography video explores early additive color processes as well as later subtractive processes like chromogenic color and the Kodachrome. The second video features a timeline of digital camera technology, starting with Steven Sasson’s first completely digital camera prototype and taking us all the way to the smartphones of today.

Color Photography – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 11 of 12. (6 minutes)

Digital Photography – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 12 of 12 (5.5 minutes)

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Camera obscura design: This diagram illustrates the components of a camera obscura (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, akg images / Universal Images Group. Rights Managed / For Education Use Only).

- Figure 2. Man working with a Camera Obscura. This projects an image of a scene onto a glass plate on which drawing paper is placed. The artist may then trace the scene as reference for later work (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, private collection / Look and Learn / Bridgeman Images. Rights Managed).

- Figure 3. This mysterious view through the diamond-paned oriel window of Talbot’s home is one of the earliest photographs in existence (Image source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 4. Albumen print by Alexander Gardner, 1862: This print by Alexander Gardner depicts bodies of Confederate artillerymen near Dunker church (Image source: J. Paul Getty Museum, www.getty.edu) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 5. The Horse in Motion by Eadweard Muybridge illustrates the artist’s preoccupation with documenting motion and his use of photography as a sequential art form. 1878 (Image source: Library of Congress) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 6. Flying Gallop Hypothesis Falsified: Galloping horse, animated in 2006 using photos by Eadweard Muybridge (Image source: Lumen Learning, Boundless Art History) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7. The Terminal by Alfred Stieglitz (American, Hoboken, New Jersey 1864–1946 New York). 1892 (Image source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Used with permission, for education only).

- Figure 8. August Sander, from left: Disabled Ex-Serviceman, 1928; Pastry Chef, 1928; Secretary at West German Radio in Cologne, 1931 (Image source: Tate. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 9. Henri Cartier-Bresson, Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare, Paris, 1932 (Image source: St. Louis Art Museum, via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 10. Umbo (Otto Umbehr), The Racing Reporter, photomontage, 1926 (Image source: University of California, San Diego via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

Candela Citations

- Photography (Boundless Art History). Retrieved from: https://www.collegesidekick.com/study-guides/boundless-arthistory/photography. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- History and Appreciation of Art II. Retrieved from: https://www.collegesidekick.com/study-guides/zeliart102/introduction-to-photography. License: CC BY: Attribution

- George Eastman Collection. Provided by: Eastman Museum. Retrieved from: https://www.eastman.org/collections. License: All Rights Reserved