Chapter 6.5: Architecture

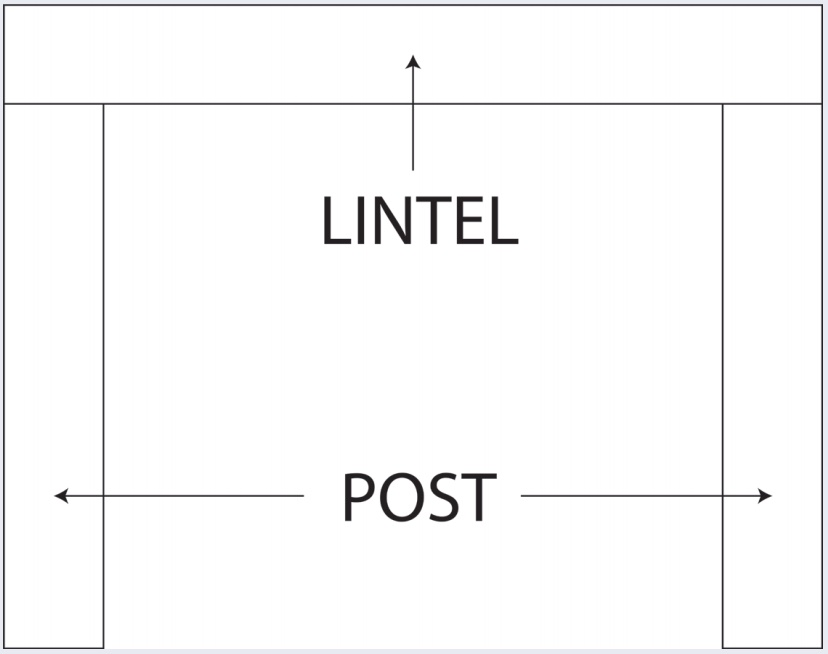

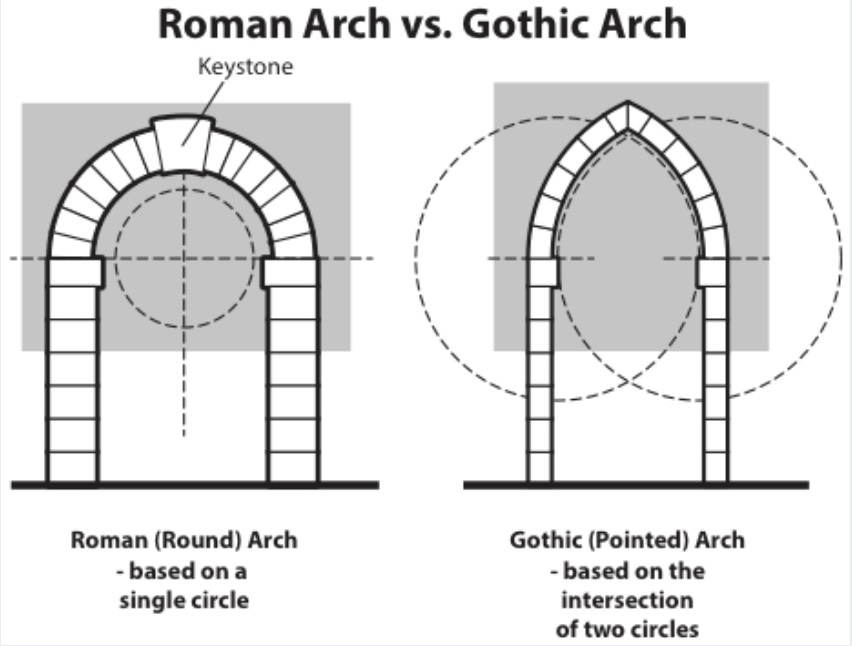

Before we start our discussion, you should familiarize yourself with the basics of building, that is, how you might create walls and place openings in the walls while supporting the parts of the structure above. The most basic method is the post-and-lintel design in which two upright beams support a horizontal one to create a rectangular opening (Figure 1). Before long, builders also devised a variety of arches, a curved or pointed structure spanning an opening and supporting the weight above, and then created further modifications of these techniques to develop barrel vaults, a series of circular arches that form a ceiling or roof, and domes, spherical-shaped ceiling or roof (Diagram of Roman Arches; Domes). They also made variations that served decorative purposes. Over time, these have been imaginatively used for a tremendous variety of structural and decorative purposes, and you should keep them in mind as we investigate an array of buildings that reflect cultural concerns and human needs of all sorts. We will classify these buildings into several groups, although noting that a great number of them were multipurpose: residential/housing, community needs, commercial buildings and centers, governmental structures, and those designed for worship.

Click on each of the drop-down menus below to expand these and learn about architecture within each of these categories.

Residential Needs

The earliest types of shelters were likely caves found by humans as they wandered to hunt and gather food and to find refuge from bad weather or pursuing creatures. The first independently standing structures were made of materials that were impermanent, that is, those found in nature—sticks, bones, animal pelts—and fashioned to create a covered space apparently as a protection from the elements. We have little evidence left for us to know fully how they were built and used, but some vestiges do remain that have enabled scholars to make reconstructions (Figure 2).

As people became more settled, domesticated animals, and cultivated crops, they developed such construction techniques as wattle-and-daub (sticks covered with mud), rammed earth (moist dirt and sand or gravel compressed into a temporary frame), and clay bricks (unfired and fired that developed alongside their evolving techniques for creating pottery vessels) (Article on Chinese round houses) (Figure 3).

They used these methods for communal living centers such as the village of Catalhöyük in modern Turkey (7,500-5,700 BCE), including common walls so that the clustered houses supported one another (Figure 4). Such building methods addressed security issues by confining entry into living spaces to openings in the roofs, with ladders that could be retracted to foil trespassers. All of these types had certain common features to meet such everyday needs as warmth, cooking, sleeping, and storage, and were usually centered around a hearth with provision for smoke ventilation. Catalhöyük also included rooms that may have been for other common purposes, varying from shrines to serving as bakeries.

The use of stone for building structures began in prehistoric times, and an example of such a structure can be seen the Scottish village of Skara Brae (3,180-2,500 BCE). The walls were made of stacked stone while entryways and some of the furniture were created using the post-and-lintel method (Figure 5). Because of the harsh northern climate, the structures were partially underground for protection from the elements. Additionally, covered walkways were created to facilitate movement among its eight units. Seven of these units apparently accommodated a family or small group, while the eighth was a common room, perhaps a workshop. In addition to cultivating crops, these villagers likely herded, fished, and hunted for food. Stone furnishing such as seating, beds, storage spaces, and other items within the single-room units were around a central fire pit (Figure 6).

With these basic methods, the humble shelter types of the Neolithic Age (c. 7,000-c. 1,700 BCE) and overlapping Chalcolithic (Copper) Age (c. 5,500-c. 1,700 BCE) provided a foundation for buildings of every sort used throughout history (with considerable elaboration of residential structures for the powerful and wealthy). Material choices eventually expanded to include first wood, brick, and stone, and later concrete and metal.

Residential palaces appeared by the time of the two great early civilizations of the Ancient Near East, Mesopotamia and Egypt, as well as those of the Aegean Sea: Crete, Cyclades, and mainland Greece prior to the development of the Greek Empire. The Palace at Knossos on the island of Crete was a grand residence for rulers of the Minoan civilization; the palace was built c. 1,700 BCE, after an earlier structure was destroyed by an earthquake, and abandoned between 1,380 and 1,100 BCE (Drawing and Floorplan of Knossos). The sprawling complex included residential areas, throne rooms, a central courtyard, and food storage magazines for crops and seafood used in the commercial trading, an important industry and mainstay in sustaining the people. An island civilization, the Minoans were in the rare position of not having to protect themselves from enemies. The Palace at Knossos and similar structures on Crete were not fortified, that is, built behind solid walls and gates to hold off invaders. The palaces were instead built with windows and colonnades, or covered rows of columns, on their exteriors, allowing free circulation of light and air.

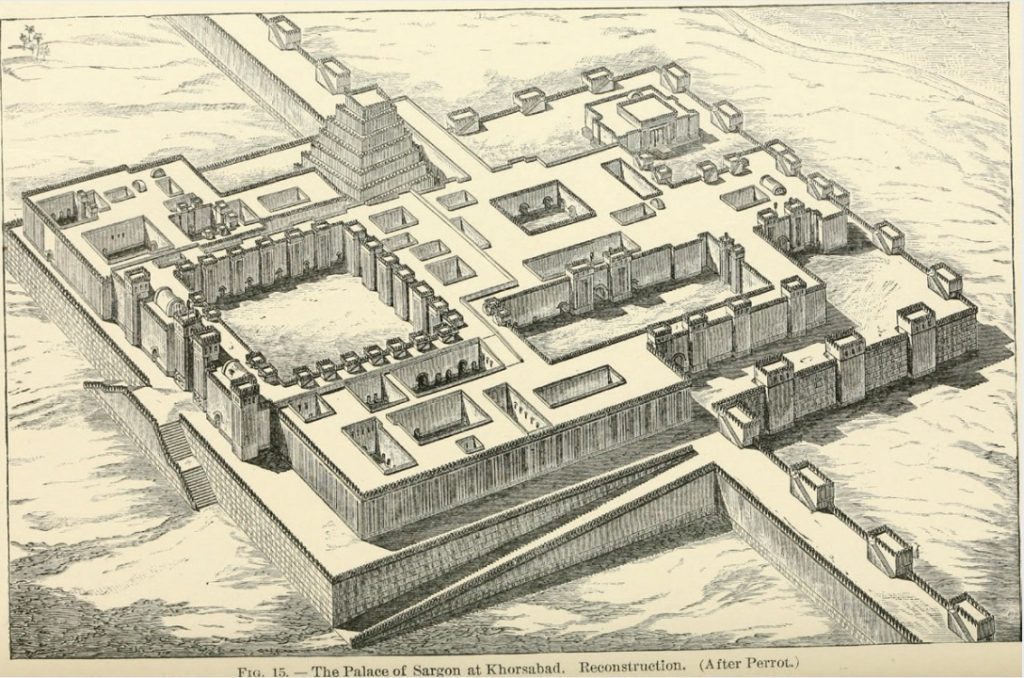

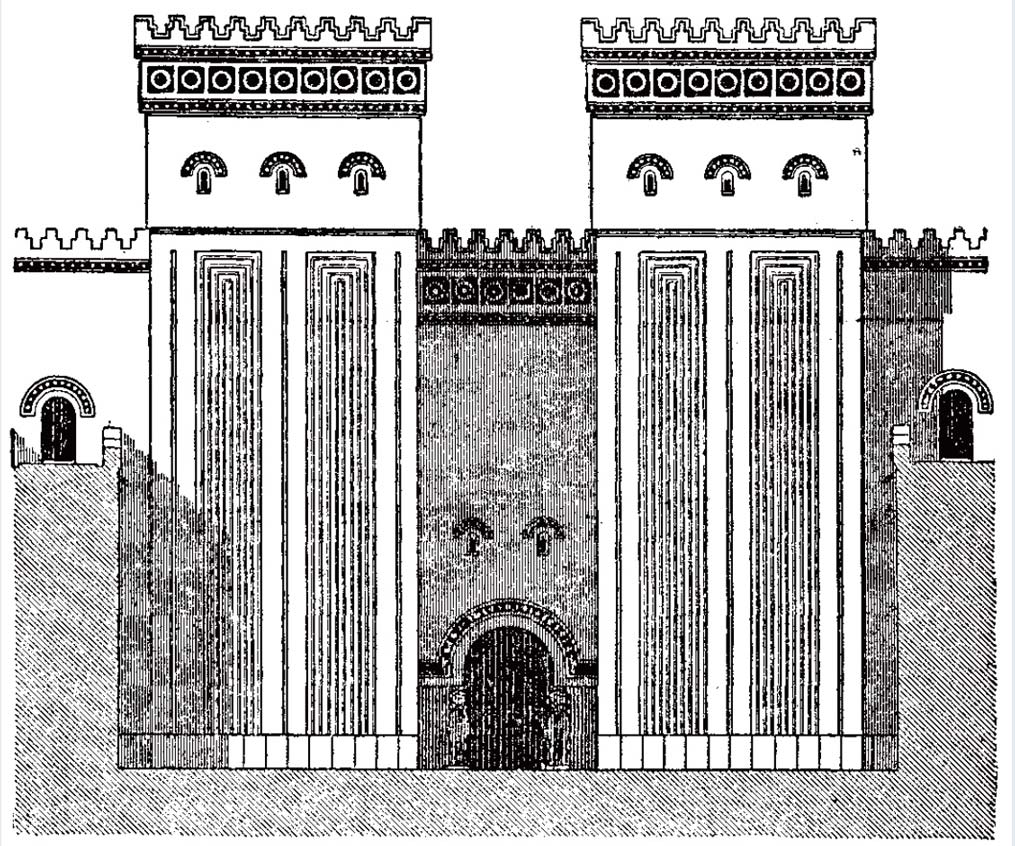

Another palace complex, that of Neo-Assyrian King Sargon II (ruled 722-705 BCE) at DurSharrukin, today Khorsabad in Iran, was clearly much more militaristic in character, evident by the surrounding defensive walls that strictly controlled access to the royal precincts (Figure 7). Even after passage through a complex and imposing gateway, one had to cross guarded courtyards and passageways to approach the king’s throne room. The structural presence was one of imposing power, as you can see from the enormous towered main portal (Figure 8). To intimidate the visitor, interior decorations further asserted the mighty and ferocious nature of Sargon II with wall carvings depicting victorious battles. The complex also included temples for worship of the deities as well as quarters for high-ranking officials and servants.

Later developments for residences include apartment buildings for urban dwellers; such multi-family dwellings have taken many forms over time, and we can view an early type, from the second-century CE Roman port town of Ostia Antica, called an insula, which is Latin for “island” (Figure 9). In middle-class “apartments” such as these, there were stores and vendors’ stalls on the ground floor facing the street. In some versions, the lower floors were for the wealthier people, while upper floors decreased in cost and desirability. The basic ideas of how to accommodate multi-family living were established by this time and have remained similar since. What has changed over time are the material and decorations used, styles adopted, provisions for electricity, water, and sewage management, and eventually zoning policies that would dictate locations, sizes, required provisions for safety, and density of occupation.

Private homes existed for the middle class and wealthy in towns and in the countryside; the latter were called villas whether they were primary residences or vacation homes. A private home in town might also have shops around its perimeter, but the accommodations for family life, entertainment, and conducting the owner’s business were generally contained in a single floor layout (Article and diagram of ancient Roman villa). After passing through an entry from the street, one entered the atrium, a courtyard with a peristyle, a row of columns within a building often supporting a porch, left open to the sky with a pool in the center to catch rainwater. A private garden was in a second area open to the elements. The mild climate led to provisions for a good measure of outdoor living as well as fresh air and sunlight during much of the year, even including indoor and outdoor dining rooms. There were rooms for sleeping, storage, and household work off the atrium and garden, as well as a space for worship, known as the lararium (Figure 10). Here, two Lares, or household gods, flank an ancestor figure; the snake below symbolizes fertility and prosperity.

Roman royalty had grand palaces, and we have good evidence of such from the retirement compound created for the Emperor Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE) in Split set on the Bay of Aspalathos in the Roman province of Dalmatia, today Croatia (Figure 11). The walled precincts with defensive watchtowers and fortified gateways included housing for his military garrison, a central peristyle courtyard, three temples, and his mausoleum, the building housing his tomb. The design, perhaps fitting for the aggressive persecutor of Christians and retired general, was quite militaristic in many ways, resembling a Roman military encampment, or castrum. The private and public imperial areas were luxurious by contrast. Like most palace complexes, provisions were made to house soldiers and servants, and it was lavishly decorated throughout with frescos, sculptures, and mosaics, images or designs created on a wall or floor made up of small pieces of stone, tile, or glass.

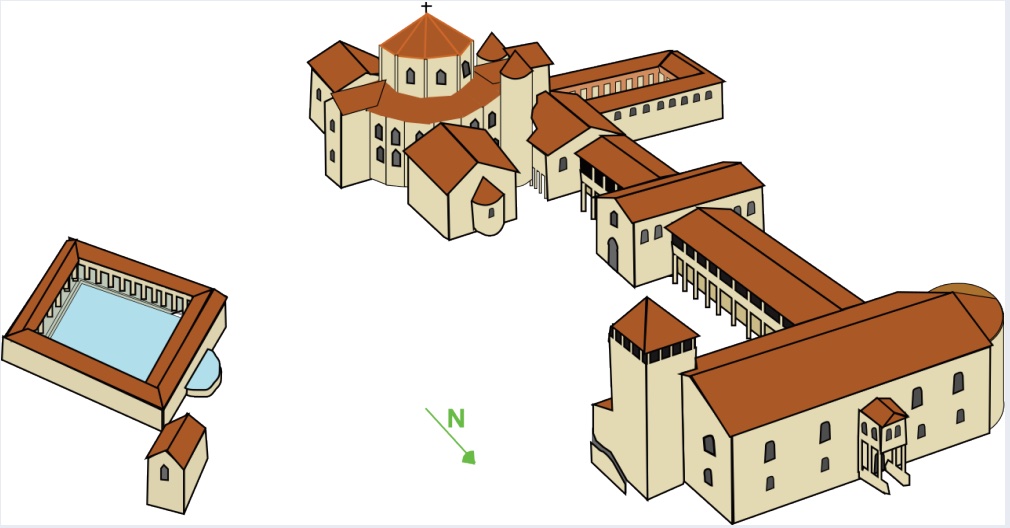

While the locations for palaces were always strategically selected, the rationale was not always defensive in character. When Charlemagne selected Aachen, Germany, as the site for his main palace (he had several), among the attractions were its centralized site within his growing empire and the healing waters of the natural spa there. In examining the reconstruction of his complex, you will notice the baths, shown to the left of the palace complex, are an important feature, as they had been in Roman society (Figure 12). He had a large audience hall, a grand portal, courtyards, housing, and an impressive palace chapel, which is the major structure still standing.

The church was an important statement for this model Christian ruler, and although it has been enlarged from its original central-plan design, the structure still carries notable features that were both impressive and influential for later medieval church architecture. Charlemagne’s throne was positioned on the gallery level, an upper level overlooking the floor below (Figure 13). The throne was above the entrance to the church, with an enormous “window of appearance” above the portal facing out into the atrium courtyard, where Charlemagne could address his Christian subjects gathered there. This emphasis on the western entryway was developed into the grand western facades of Romanesque and Gothic churches.

The Doge’s (Duke’s) Palace in Venice is another impressive statement of rulership wed to Christian leadership (Figure 14). With its façade on the waterfront, the church of San Marco sitting directly behind it, state offices located across from it, and the communal, open-ended piazza, or courtyard, between them, the palace literally connects the secular, religious, social, and political realms of Venetian life (Figure 15). Public courtyards at the heart of cities became typical during the Italian Renaissance, as did private, interior courtyards in the center of Italian homes for rulers, wealthy aristocrats, and high church officials. As an official governmental center and residence, this Venetian palace included private quarters for the Doge along with meeting rooms and council chambers, all richly decorated with marble, stucco, and fresco and including iconographic themes related to Venice, its history, and civic identity.

In Japan, the fourteenth-century Himeji Castle, built as a fort by the samurai Akamatsu Norimura, was situated dramatically atop Himeyana Hill (Figure 16). Though a defensive posture was its primary motive, the great beauty and lyrical appearance of its curved walls and rooflines are its predominant effects. It has been called the “white heron” in response to the impression it gives of a great bird about to take flight. The complex, again, has many purposes and comprises eighty-three different structures. The grounds include huge warehouses, lush gardens, and intricate mazes. Despite its fairytale looks, its defensive systems are complex and effective, including moats, keeps, gates, towers, turrets, and mounts and brackets for a variety of weapons. It has withstood numerous attacks and natural disasters over the centuries.

The final such royal complex we will explore is the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet, established in 1645 by the fifth Dalai Lama; the palace functioned as the spiritual and governmental center for Tibetan Buddhism until the fourteenth and current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso (b. 1935), fled for political refuge in 1959 (Figure 17). The basic purpose of the palace was that of a Buddhist monastery; its original foundation was centered on two chapels of historical and spiritual significance to the order of monks. The palace is named after Mount Potalaka, the mythical abode of the Bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara, and the paradisiac implications are meaningful to devotees.

As at Himeji, the hillside is a striking component of its appearance, and the enormous complex makes a very dramatic presentation. Indeed, whether intended for defensive purposes or not, its imposing appearance is often a very important feature for royal architecture. The impression of this palace’s organic relationship to the mountain is enhanced by its sloping walls, flat roofs, and numerous stairways that lead to its various structures. The complex includes living quarters for the Dalai Lama and the monks as well as governmental offices, a seminary, assembly halls, shrines, libraries, storage rooms, and numerous chapels. It includes statues and portraits of historical and spiritual leaders and many devotional and didactic depictions painted on walls and banners, and works for meditation and prayer. Burial mounds and tombs contain the remains of lamas and important scriptures.

The residential structures of the wealthy of previous eras have often been lost to us; however, we can examine some of the aristocratic family homes of the last several centuries to gain insight into some of the additional trends for creating dwellings that go far beyond the need for simple shelter and that show some of the design ideas devised by artists and architects. The house created for Lord Burlington in 1729 in Chiswick, England, is a good example of the Neo-Palladian style of architecture (Figure 18). Andrea Palladio (1508-1580, Italy), a Venetian Renaissance architect, deeply studied ancient Greek and Roman architecture and architectural theory and developed new designs based on those but better fit to the means, methods, and needs of his day. His ideas were popular and have remained widely influential throughout the West to this day.

Lord Burlington created his neo-Palladian villa design under the influence of Palladio’s ideas and those of other related designers. The basic idea here derives from a combination of a Greek temple front and a Roman dome, here supported by an octagonal drum, or circular or multi-sided base. Lord Burlington planned the house to showcase his fine collection of pictures and furniture and his architectural library as well as to provide comfort for his family living there. Great attention was paid to the surrounding gardens, and their design was very much a part of the overall scheme. Inspired by Roman gardens, they were designed by his friend William Kent (c. 1685-1748, England), an architect and early landscape architect, and included classicizing statues and miniature temples of a sort that were popular in English gardens of the day, thereby providing interesting and restful stopping points to a refreshing stroll outdoors. The logic and order of the layout of the building and grounds as well as the villa’s sense of grandeur led to its admiration and emulation by other builders who sought a similar elegance.

The Neo-Palladian style was carried to the United States by Thomas Jefferson for the campus of the University of Virginia, the state capitol of Virginia, and his own home of Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia (Figure 19). Jefferson adapted ideas he gathered while U.S. Ambassador to France by using humbler materials such as the red brick made from local clay that he considered a better choice for a less pretentious statement than marble or limestone. At Monticello, he also brought the structure lower to the ground and added a wooden balustrade, a railing supported by upright supports, to the roofline. Nonetheless, its Palladian design origins are clear. The interior of the house is full of provisions for Jefferson’s notable intellectual and work habits such as his bedroom that opened into his office, his workrooms, and his collections of American artifacts.

In the United States of the late nineteenth-century Gilded Age (c. 1870-1900), a time of rapid technological, commercial, and economic expansion, wealthy industrialists built enormous mansions in cities and at the seaside resorts or mountain retreats they favored. Among these, the Vanderbilt family (whose wealth came from shipping and railroads) commissioned several notable residences, mostly in the French-inspired Beaux Arts style, a period and style known in the U.S. as the American Renaissance (1876-1917).

One of these residences was The Breakers in Newport, Rhode Island, a lavish resort area replete with such structures (Figure 20). The oceanfront house, designed by Richard Morris Hunt (1827-1895, USA), has seventy rooms on five floors and covers nearly an acre of land on a thirteen-acre lot with elaborate gardens. It was built with the most lavish material such as marble and wood from around the world and was decorated with rich and sumptuous furniture, fittings, and valuable artwork, as can be seen here in the library (Figure 21). Clearly a residential structure of this type went far beyond the simple needs of housing to shelter a family from the elements and served to make a very grand and ostentatious statement of wealth and power.

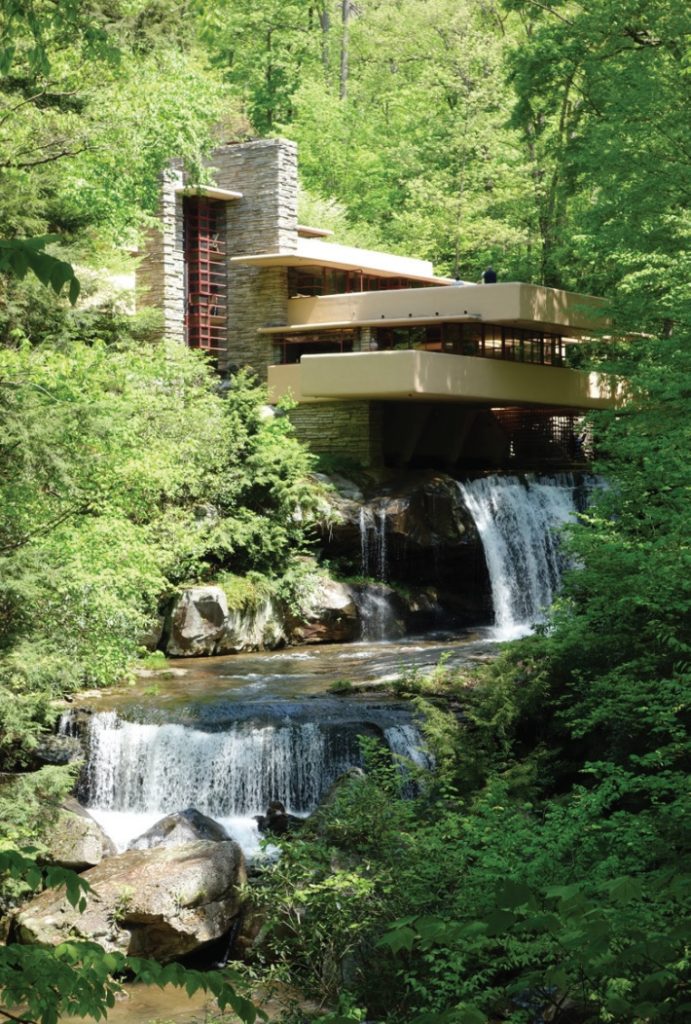

By contrast to design ideas of the architects who catered to the wealthiest Americans, a new conception for providing living space came into being in the early twentieth century with Frank Lloyd Wright, who developed what he called the Prairie Style. He sought to counter the blocky forms that had become the standard for American homes with a structural sweep that hugged the ground, echoed the landscape, and fostered communication between the spaces in the house and the natural elements around it.

Perhaps the epitome of this thinking was realized in Wright’s design for Falling Water, a western Pennsylvania mountain home he created for the Kaufmann family of Pittsburgh (Figure 22). At their request, he incorporated elements of their favorite recreation spot into the design: the rocky outcrop where they held picnics is in the living room, and the adjacent Bear Run waterfall pours out beneath the house’s cantilevered terraces, self-supporting rigid structure projecting from the wall. Like most of Wright’s houses, the place has flowing interior space, a great number of windows, and abundant natural light, as well as carefully coordinated use of stone and wood to incorporate the structure into the natural setting.

Community and Government

Clearly, many of the palaces and complexes we have explored included accommodation of community government needs. There were others throughout history that had somewhat more pointed community needs in mind for their creation but were often combined with other purposes as well. From the time of the rise of the earliest civilizations, the needs for government and religious expression often coalesced.

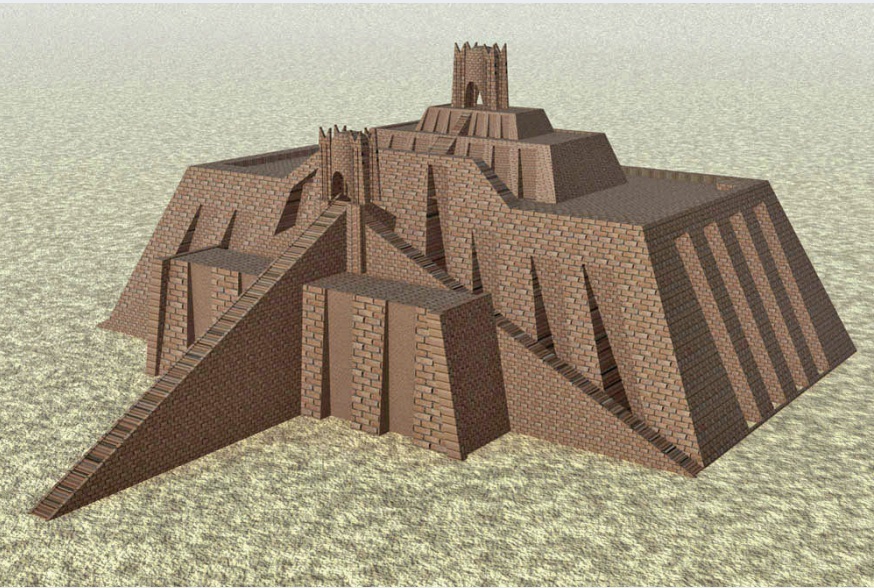

In the Mesopotamian Valley of the ancient Near East, today Iraq and Iran, we see this exemplified in the structure of the Ziggurat of Ur (Figures 23 and 24). With the idea that the deities resided in the heavens, the ziggurat was conceived as a man-made mountain that served as a base for the temple, raising it closer to the celestial regions where the deities were. The pathways to the temple at the summit were steep and the approach to the gods was appropriately aggrandized and formalized. At the same time, the basic platform structure was part of a complex that included the provisions for a variety of other community services, record keeping, and commercial and governmental functions. The compact complex was located at the center of the community and in many aspects became the hub of life.

The people of the ancient Near East built with mud brick, sometimes baked, that has not proven to be durable, so the remains of these structures, constructed from around 2,400 BCE until the sixth century BCE, are generally not well preserved. Still, there are sufficient clues in the ruins to reconstruct the ways they were built and used.

The Romans generally made provisions for community functions in the forum, an open public space at the center of each city; the cities were often laid out in a grid plan organized with areas dedicated to various types of industrial, commercial, communal, and residential needs. The number and types of buildings varied, but they often included temples, libraries, markets, public baths (thermae), and judicial structures. The Forum at the heart of Rome was the site of numerous architectural statements and additions for the public good that were created by successive rulers.

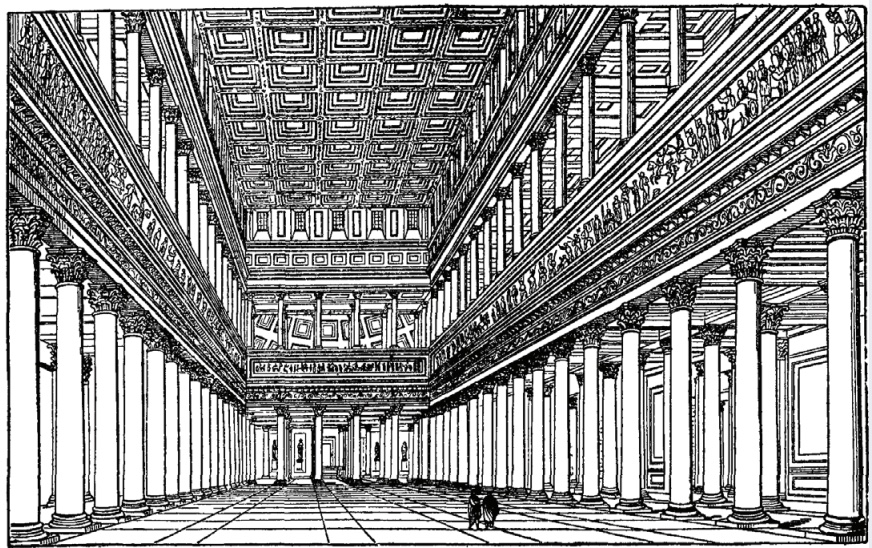

One of the most influential of the buildings in the Forum of Trajan in Rome was the Basilica Ulpia, a center for law courts, business, and public gatherings (Figure 25). The basilica included a long and broad open center space, a nave, flanked by aisles that fluidly expanded the area (Figure 26). This design provided a readily adaptable concept for other purposes, most notably perhaps the congregational space needed for Christian churches that would arise in later centuries as the Christian populace grew.

Significant community spaces sometimes have as their boundaries adjoining but separate architectural structures. These spaces are nonetheless important gathering places that need to be considered as such and in connection with the surrounding architecture that defines them. The National Mall in Washington, D.C., is one such place (Figure 27). We identify it by its location within the capital city and by its placement among all the government and other public/community buildings that line and define it. One only has to see it as a site for a presidential inauguration celebration or other large public gatherings to realize its significance as a community center.

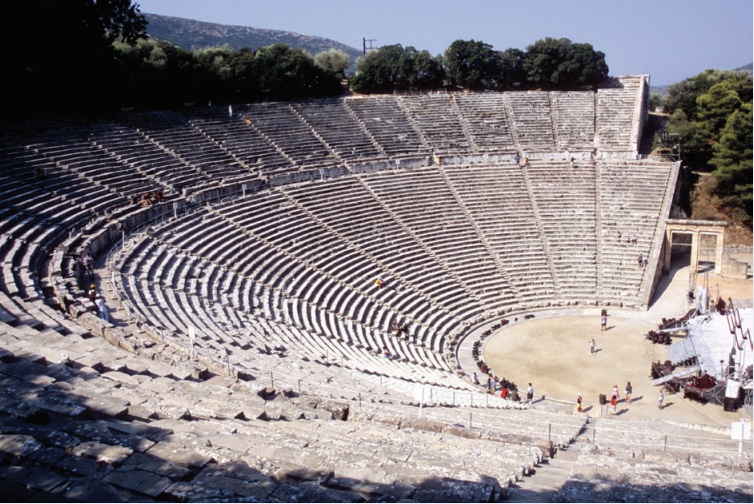

Community needs for ceremony and entertainment have been addressed with specifically purposed architectural works since antiquity as well. Both the Greeks and the Romans designed and built theaters, outdoor structures for dramatic performances, and amphitheaters, round or oval buildings with a central space for events, that provided models for such structures to this day (Figures 28 and 29) While the basic concepts were devised by the Greeks to present religious festivals and ritual dramas, the Romans with their great ingenuity in engineering and material development added considerably to the potential for these designs to cater to changing needs and broader applications.

One of the most important contributions to the history of architecture was the Roman development of concrete for use as building material. Its greater strength, flexibility, and potential for adaptation made concrete far superior to the cut stone used to that point. These advances enabled the Romans to create new architectural forms by expanding the types of vaulting and means of spanning space they had previously used. Both of these important community structures, the theater and the amphitheater, were enlarged and put to new uses because of the Roman architectural contributions.

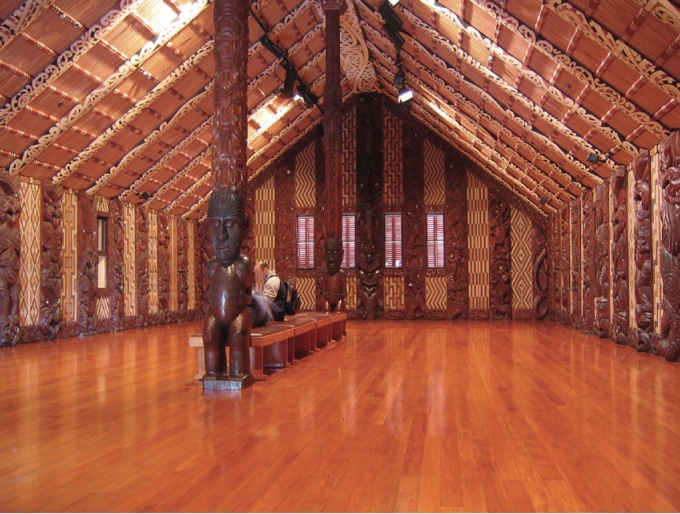

Pacific Island cultures, as do those of Native Americans, particularly venerate tribal heritage and so celebrate the communal events related to their heritage. Native North Americans of the Kwakiutl Nation created the clan totems, objects or animals that hold significance for a group of people, at the Wawadit’la, also known as the Mungo Martin House in honor of the chief and artist who built it in Victoria, British Columbia (Figure 30). The recognition and celebration of their shared culture is expressed, as well, in the Meeting House of the Maori people at Waitangi, New Zealand, with its deep front porch and big open hall for group events (Figures 31 and 32). Additionally, the carved and painted decorations inside and out have specific iconographic and symbolic significance for the individuals who gather together at such communal sites.

Commerce

Buildings for commerce have appeared over time. Early systems of trade and barter in some places eventually became formalized in ways that required marketplaces and commercial establishments with temporary or permanent housing. While open-air markets with vendor stalls continue to be used in many places, in others shops or full buildings evolved for commercial and service transactions.

An early example appeared in ancient Athens, Greece, in the area where the open market or agora, was also located. The Stoa of Attalos, built by King Attalos II of Pergamon (r. 159-133 BCE), was comprised of a two-story covered walkway made of marble and limestone with columns on one side and a closed wall on the other (Figure 33). Along the closed wall, there were twenty-one rooms on each level with each room providing space for a shop. These rooms were similar in character and purpose to those we noted on the ground floors of Roman villas and apartment buildings, but they provided for a more concentrated shopping area.

Our modern provisions for shopping centers and department stores were designed with different ideas about merchandising, sales, and consumerism but, as we have seen with the rapid rise of on-line shopping for durable and perishable goods, this scenario will likely be ever evolving. Indeed, grocery and department stores may become completely passé. But their development in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries presented new possibilities for architectural design.

An example is the Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Store in Chicago, designed by Louis Sullivan (1856-1924, USA) and built in 1904 (Figure 34). One of the early applications for steel frame, or “skeleton frame,” construction that made the development of skyscrapers possible, this sort of building also opened new possibilities for retail and office space. Here, the large ground-floor windows and corner entrance could provide a great deal of display space for attracting pedestrians while the expansive multistory interior offered shoppers a wide array of goods, especially compared to the sorts of small shops and markets that had been its predecessors.

Not only the structure but also the decorative approach was innovative, as Sullivan combined Beaux Arts ideas with Art Nouveau motifs in the building’s surface design (Figure 35). The elaborate, curvilinear, plant-based motifs central to the Art Nouveau movement, c. 1890-1910, in cast metal relief panels above the doors and ground floor windows added to visual appeal for potential customers.

New designs emerged for other commercial firms in this era as well. The Austrian Postal Savings Bank in Vienna, Austria, designed by architect Otto Wagner (1841-1918, Austria) has a huge multi-story façade covering a broad open interior space on the ground level; its sleek and modern aesthetic was startlingly new and different when it was completed in 1905 (Figure 36). One of Wagner’s aims in the design was to create a sense of strength and solidity that engendered trust and a feeling of financial security in customers. The main banking customer area is filled with natural light. Wagner used marble, steel, and polished glass for the simplified decoration of the reinforced concrete building, turning away from the Art Nouveau aesthetic and replacing it with his sense of modernism.

The use of steel and reinforced concrete that facilitated the advent of the skyscraper truly revolutionized architecture and began a contest for height that continues today. Wealthy entrepreneurs and ambitious developers from around the world have joined in the competition for buildings of modern distinction. One example is the Chrysler Building in New York City, designed by William van Alen (1883-1954, USA) (Figure 37). Its décor in the Art Deco style (c. 1920-1940), including the ribbed, sunburst pattern made of stainless steel in the building’s terraced crown, celebrates American industrialism and the automobile. At 1,046 feet, the Chrysler Building was for eleven months after its completion in 1930 the tallest in the world. (It was surpassed in 1931 by the Empire State Building at 1,454 feet.)

A more recent example is the Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lampur, Malaysia, designed by César Pelli (b. 1926, Argentina, lives USA) (Figure 38). Inaugurated in 1999, they were the tallest buildings for several years and remain the tallest twin towers to this day. The buildings’ design motifs are inspired by Islamic art and culture; for example, the shape of each tower is the Muslim symbol of Rub el Hizb, or two overlapping squares that form an eight-pointed star. Both structures house commercial and business concerns and symbolize the architecture of modern business.

In the late twentieth century, architectural ingenuity, new materials, and the potential of computer design led some architects to develop radically innovative approaches to structures that might house any number of different types of needs. Among the most innovative in this regard is Frank Gehry (b. 1929, Canada, lives USA), who has designed buildings all over the world including museums, business towers, residences, and theaters.

In Los Angeles, he created the Walt Disney Concert Hall, completed in 2003. (Figure 39) Using titanium sheathing for multiform, swooping curvilinear forms and volumes, his buildings are sculptural in effect from a visual standpoint. Yet in each case, his buildings have proven effective and dynamic in creating spaces for the activities they house. The acoustics of the concert hall are widely praised as is the beauty of the architectural form in capturing the whimsical spirit of Walt Disney, the creator of so many American comics, cartoons, and movies.

Worship

Structures for worship, as we have noted, were sometimes combined with or situated near those created for other communal needs. We saw this with the ziggurat, in the Roman forums, and in palaces, among others. But we also have a considerable history of architecture intended solely for religious purposes. From early times, there were two distinctive conceptions for a sacred building: whether it was a house for the deity or a house for the worshippers. Beyond that, it might be for individual devotional activities or for accommodating a congregational group. We can keep these points in mind when examining the types of building designed for these goals.

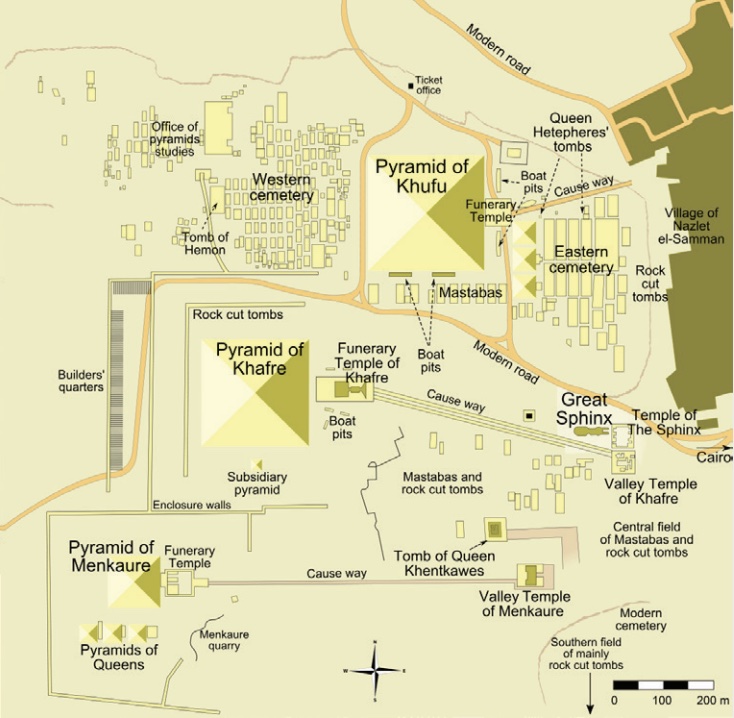

Among the earliest examples are the pyramid complexes from ancient Egypt (Figure 40). The pyramids were tombs composed of millions of large stones in mathematically regular geometric structures carefully oriented to the stars. Pyramids evolved over thousands of years out of pre-Egyptian burial practices that began with placing heavy stones over gravesites to protect the occupants and their grave goods buried within.

The Egyptians created these elaborate and massive groupings of buildings for the royal dead on the west bank of the Nile River, creating a necropolis, or city of the dead. At Giza, the body of the pharaoh or other royal family member was brought down the river from the palace to the valley temple on the edge of the pyramid precinct. After priests mummified the body of the deceased and prepared it for entombment, the body would be taken to a mortuary temple near the pyramid (Figure 41). That temple was the site where ceremonies were carried out at the time of the mummy’s placement within the pyramid, as were the perpetual rituals required to honor the king in the afterlife.

There were also temples for the living that the king would have had commissioned and served. One example is the Temple of Horus at Edfu, which has a number of typical features, although it was built relatively late in Egyptian history. It is of the pylon type, so named for the two upright structures that form its monumental façade and flank the main ceremonial portal (Figure 42). The approach to temples was often along an avenue of sphinxes, imaginative hybrid creatures, part human, part animal, that led to the main door. Beyond the pylon wall was an open courtyard (Figure 43) and then a hypostyle hall, a structure with multiple rows of columns that support a flat roof, leading to the sanctuary. Typical of many sacred structures is this sort of staged progression by which one moves from the public or profane spaces through gradually more sacred, and often more restricted, areas that lead ultimately to the most sacred and reserved part. It is often the case that only priests or otherwise consecrated and dedicated persons are allowed in the sanctuary, the innermost and holiest space, while most of the congregation or worshipers are confined to less sacred parts of the temple, and the general public may be denied access to the premises altogether.

Greek temples like that devoted to Hephaestus in Athens, Greece, were not congregational at all (Figure 44). They were designed as houses for the deity with a cella, or room, inside that was provided for the cult statue. Sometimes, there was also a cult treasury room within the temple, but ceremonies and sacrifices were conducted outside in the temple courtyard. Like the ziggurats, Greek temples incorporated the belief that the gods were on high, in the celestial realms, so they were often located in an acropolis, or sacred city high on a hill.

This can clearly be seen in the case of the Parthenon, dedicated to the goddess Athena, the patron of the city of Athens (Figures 45 and 46). As in all Greek temples, a mathematical relation can be found ordering the size and relation of the Parthenon’s elements. The length to width of the structure, the height to the width, the diameter of the columns, and their spacing all conform to the golden ratio of 4 to 9. This use of a single relation between the various elements of the structure gives it an aesthetically pleasing, unified, and more solid appearance, as does the use of several optical corrections. The columns lean slightly inward, and the stylobate, the base upon which the columns stand, bows upward slightly in the middle, both to give the appearance of being completely straight and flat.

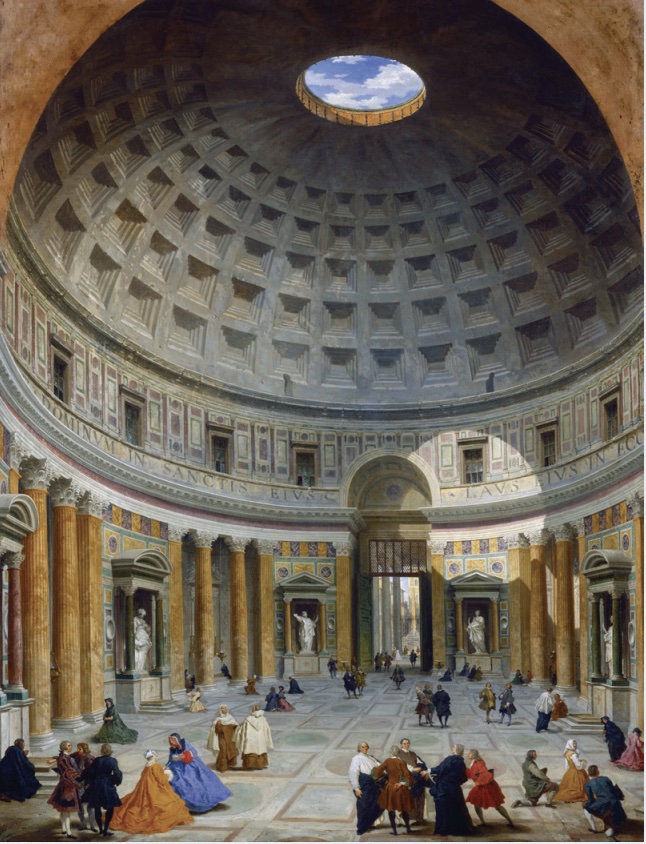

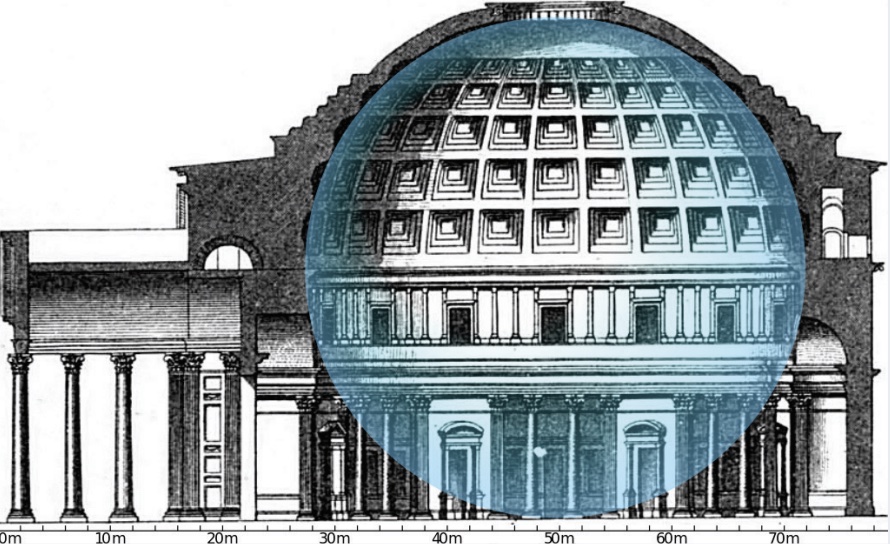

Roman temples were often built in emulation of those of the Greeks, but they made many practical changes to the designs and often placed them in the center of the community, as opposed to the separated locations preferred by the Greeks. An important and very innovative temple design was created during the early Imperial era to honor the pantheon of nine planetary deities. To address the honor of the group, rather than individual gods, this temple, the Pantheon, took a different form (Figure 47).

The building had a traditional temple front made up of columns supporting a triangular pediment. Rather than continuing into a rectangular, gable-roofed structure, however, the interior was an open circle with cult statues arrayed around its perimeter, each in a separate niche, or shallow recess in the wall (Figure 48). That circular interior, acting as a drum, supported a huge domed space with an oculus, a circular opening, at its summit. Combining the circles of drum and dome creates a perfect sphere (diameter = height) (Figure 49). The whole of the structure was constructed using the ingenious Roman concrete, which allowed the creation of an unsupported dome— greatly facilitated by the use of coffers, or recessed squares, which tremendously reduced the dome’s weight. The circle and square are not only featured in the ceiling construction, the repetition of those shapes is carried out in all of the architectural and decorative elements of the Pantheon’s interior and exterior.

In addition to these singular features, the Pantheon was the first temple structure the congregation was allowed to enter. Once Christianity supplanted the ancient Roman religions, spaces with large, open interiors would be needed to house the faithful attending mass. The Pantheon served the needs of a Christian church well, and it was converted in 609 CE. Its adaptation as a Christian church prevents our viewing it as it was intended to be used, but the Pantheon still stands in well-preserved condition and with little alteration to the structure and basic décor of fine marbles for the floor and interior columns, due to its continuous service as a house of worship since it was built in the second century CE.

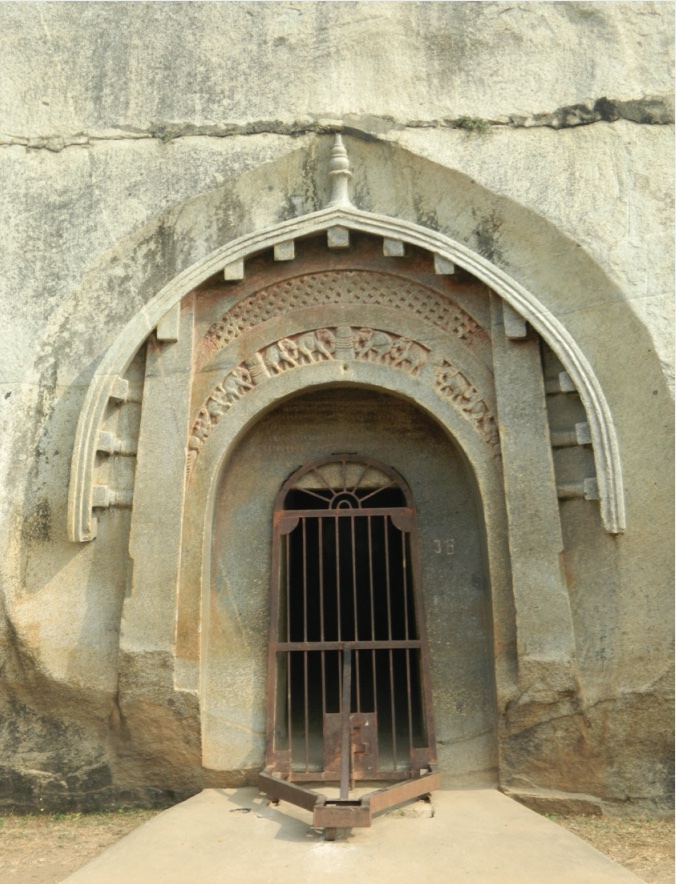

Some of the earliest evidence of worship in India shows that it was conducted in caves; we also see attempts to create worship spaces by excavating the living rock and creating larger caves for this purpose. While rock-cut architecture exists in many places around the world, its extent in India over the centuries is unsurpassed and, due to its great durability, many fine examples of it are preserved.

A very early example is the Lomas Rishi Cave in the Barabar Hills from the third century BCE (Figure 50). Because it is unfinished, we have a good idea of the methods and plans for the excavation, which included the addition of a large rectangular chamber leading into a smaller circular one. The sculptural treatment of the frame of the portal is a good example of the ways in which early architecture and decoration in stone imitated prior work in impermanent materials such as wood, as was the case for early architectural design around the world. Here, the designs simulate lattice, beams, and bentwood construction.

Later Indian worship structures such as the Brihadeshwara Temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, from the eleventh-century Chola Dynasty era, show the great complexity of conception of this type of worship space (Figure 51). The tower at the far end is over the garba griha, or sanctuary, and as with the Temple of Horus at Edfu, there is staged progression from the profane (everyday) space to the most sacred. The whole is raised on a platform, a feature also seen in many sacred structures. Here, one must begin the approach by entering a gated courtyard, then ascend the stairs, and pass through the mandapa, or audience hall, before approaching the sanctuary. Outside the main temple but within the courtyard are subsidiary temples and shrines, as the worship is polytheistic, that is, with a great number of diverse deities.

As is the case with most Hindu and Buddhist temples, although there are certainly ceremonial and ritual functions that are priestly duties, there is no restriction for lay people entering the sanctuary as the relationship to the deity is generally considered to be a personal one, not mediated by a priesthood.

The coexistence of Hindu and Buddhist deities evidenced by their shrines appears at many sites, though usually one or the other predominates at a given site. In addition to temples, another basic structure associated with Buddhism is the stupa (Figure 52). One of the oldest stupas is in India where Buddhism first arose, at Sanchi in Madya Pradesh. Established in the third century BCE, it was conceived as a burial mound of a type, as it was believed to contain part of the earthly remains of Sakyamuni, founder of Buddhism. Surrounded by a tall stone fence, it is designed for the devotee to enter the fenced area and circumambulate, or walk around, the stone-faced, rubble-filled mound.

A great deal of symbolism is associated with the form including a yasti, or mast, rising from the center of the dome that stands for an axis mundi, or axis of the world, separating the earth from the sky above. The fence and gateways are also covered with mythological carvings related to Buddhist and Hindu beliefs. When the Buddhist stupa form migrated to China, Japan, and elsewhere, the design evolved to include native architectural traditions resulting in the stupa form becoming the multi-tiered pagoda, a Hindu or Buddhist sacred building.

Centers for Islamic worship are housed in architectural structures known as mosques. While churches and temples associated with other faiths are generally oriented to the four cardinal directions, usually with the altar toward the east where the sun rises, the mosque will always be situated so that the worshippers face in the direction of the qibla, a fixed wall aligned to face Mecca, the city that is the epicenter for Islam. This orientation remains consistent regardless of where in the world the building is set. While several different standard architectural forms exist for a mosque, its most common distinguishing exterior feature is the minaret, the slender tower from which the call to prayer is issued. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque shows six minarets while four are common at other sites (Figure 53).

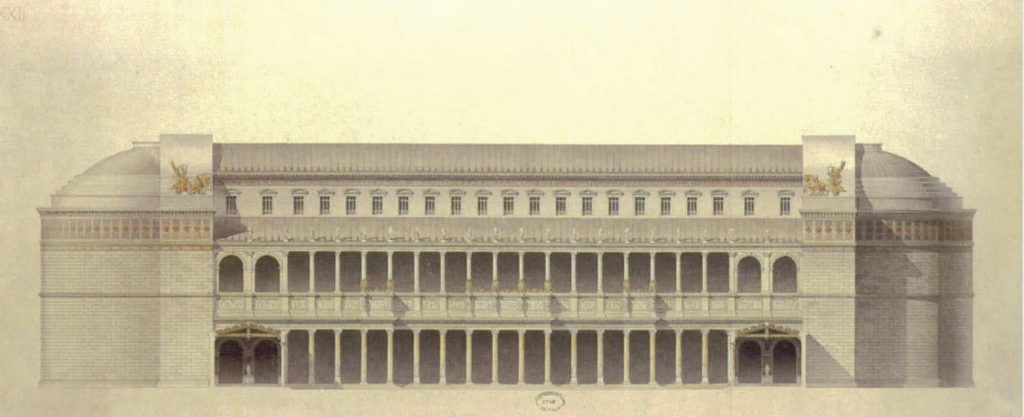

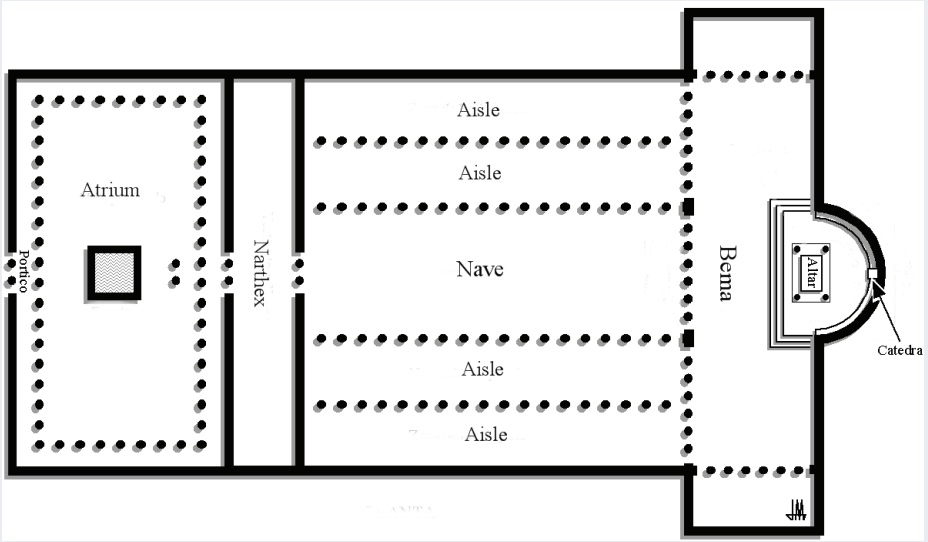

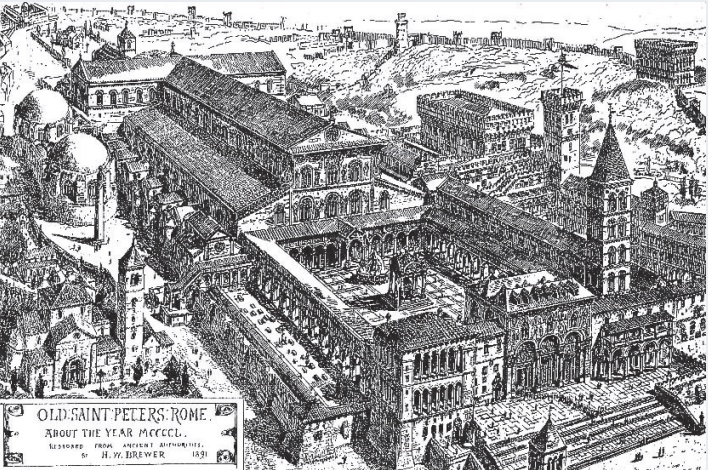

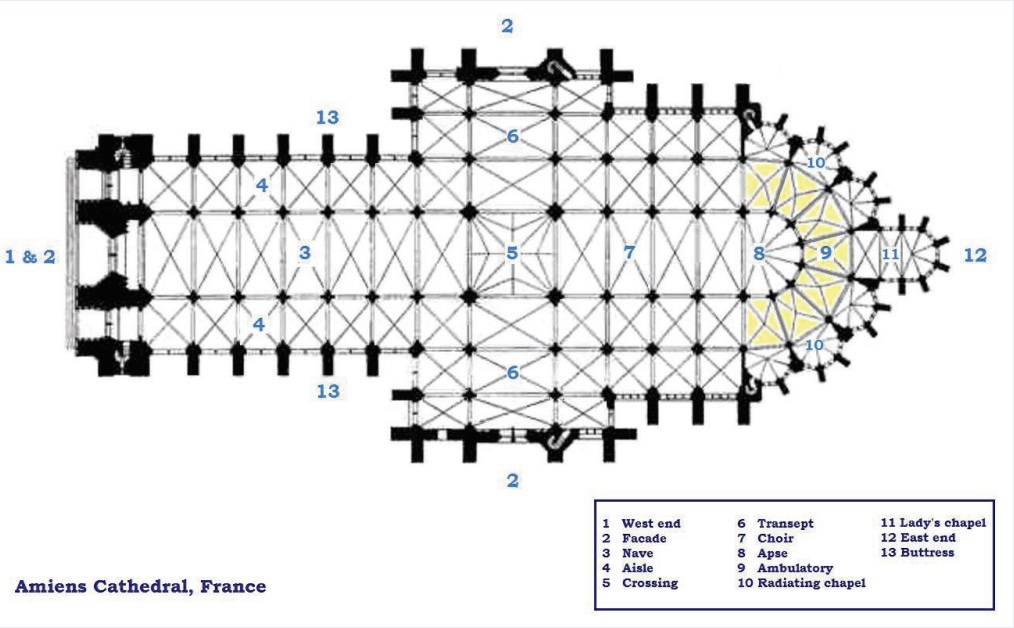

The most basic architectural form for Christian congregational churches is the basilica, a structure of longitudinal plan adapted from the Roman public building form (Figure 54). The Roman basilica had an entrance on one long side that led to the large open interior space, the nave. The Christian basilica, unlike that used by the Romans, has an entrance on one end, is divided into a center nave and side aisles along its length, and holds a semi-circular apse, or recess, containing the altar at the opposite end of the longitudinal building from the entrance (Figure 55). As in other centers for worship we have seen, the holiest part of the church is farthest away from the most profane or public spaces. The progression from one end of the church to the other is a processional ritual, enhanced by the long rows of columns flanking the nave, the long exterior walls, that were often heavy wood or masonry structures until the Gothic era, and the filtered light that played among the structural components.

This was the case in Old St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (Figure 56), built in the fourth century CE on the model of the Roman basilica type. Also based on the Roman secular model was an atrium that was placed before the entrance. The original St. Peter’s was the center of the Christian world for centuries and a model for church architecture, but it was replaced during the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods with the much grander structure that exists today in Rome.

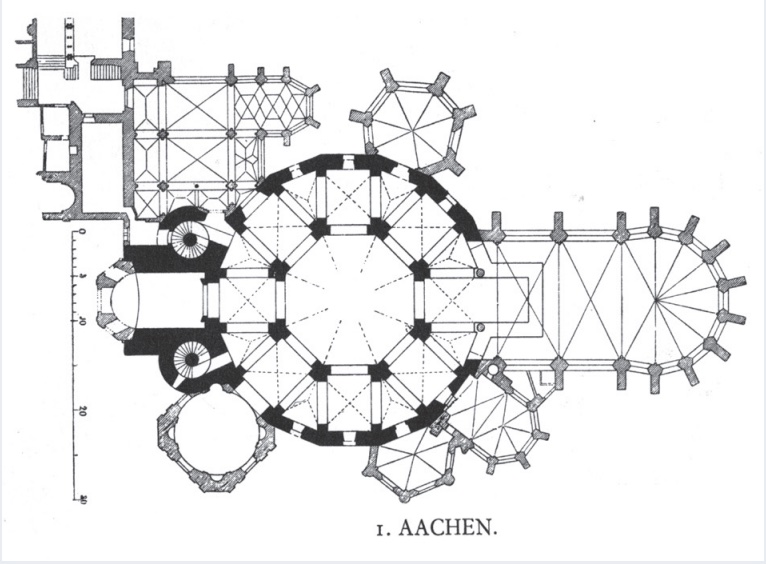

Christians in the Western Roman Empire used the basilica, or Latin cross, plan, but those in the Eastern Roman Empire, more commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, also employed the central plan, which had its origins in the circular plan, such as that used for the Pantheon. In the West, however, the circular, or central plan, church was used for a palace church such as Charlemagne’s at Aachen (Figure 57), mausoleum (tomb building), or martyrium (site marking the death of a martyr, someone who died for their faith), where the placement of the altar does not need to address large crowds.

Perhaps the most familiar basilica or Latin Cross churches are those in the Gothic style in Europe that began in 1144 (Figure 58). When these structures were being built, they were not called “Gothic.” Instead they were called “opus francigenum” or “work of the Franks” because of its origination at the Abbey of Saint-Denis. The term “Gothic” was coined in the sixteenth century, originally meant as an insult, by artist and historian Giorgio Vasari (1511- 1574, Italy). He wanted to distinguish the architectural style, based on forms from ancient Greece and Rome at that time practiced in Italy, from medieval Christianity and its associations with the destruction of classical learning and culture. The Goths were Germanic tribes that he believed had invaded and destroyed the refined culture of ancient Rome. His pejorative name has persisted but without its originally negative connotation.

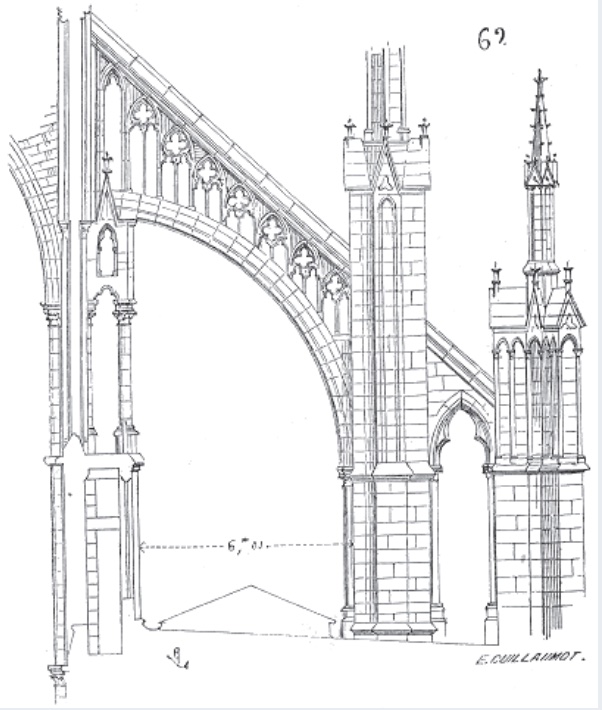

That first Gothic architecture was seen in the rebuilt choir at that Abbey Church of St. Denis, outside Paris, France, that was designed by the Abbot Suger and completed in 1144 (Figure 59). Several of the defining features of the Gothic cathedral were used there: the pointed arch, the ribbed vault, flying buttresses, and stained glass windows. Unlike the Roman circular arch, the Gothic or pointed arch is formed by two arcs with parallel sides (Figure 60). A ribbed vault is formed at the intersection of two barrel vaults, with stone ribs sometimes added to support the weight of the vaults. The flying buttress is a load-bearing component located outside the building, connected to the upper portion of the wall in the form of an arch (Figures 61 and 62).

The combination of the pointed arch, ribbed vault, and flying buttress allowed the height of the interior spaces to be dramatically increased and the thickness of the outside walls dramatically decreased. This development led to the widespread use of stained glass throughout the church and the addition of the rose window, a circular stained glass window dedicated to the Virgin Mary, usually found above the main portals (Figure 63). The much larger number and size of windows allowed natural and multicolored light to flood the interior of formerly dark churches as was the case at St. Denis (Figure 64).

Gothic churches were built throughout continental Europe and England, with regional variations, in the center of their communities usually, especially if they were cathedrals, or Bishop’s churches. Whether viewed from a distance approaching a town or standing within the cathedral itself, the building soared above all others as it reached to the heavens. They were filled with architectural and sculptural ornamentation to teach the doctrines of the Church, Bible stories, and the accounts of Mary, the Apostles, and the other saints. Portals were especially the focus of sculptural effort. Standing figures in high relief of prophets, kings, and saints graced the sides of the jambs, or upright supports to either side of a door (Figure 65). And many other sacred and secular figures, relief sculptures, often of Jesus and symbols of the Four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, were included in the tympanum above the doors (Figure 66). The architects, masons, and sculptors responsible for these monumental buildings were highly skilled and creative, and Gothic cathedrals remained the dominating forms of the Western urban landscape until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when the modern structural steel skyscraper surpassed them in height and scale.

The overall effect of walking into a Gothic cathedral is to be drawn upward into a vast, light, and airy space, and to be dislocated from the physical and drawn into the spiritual (Figure 67). This effect is the epitome of the Gothic Christian view that the physical and sensual world is to be ignored or even disdained in favor of chastity, spiritual awareness, and religious devotion.

Christian churches of all denominations today generally follow the basilica model, but the sanctuaries vary considerably for diverse ceremonial practices. The Gothic type, with its pointed arches and glass windows that filter mystical light into the interior, is still common.

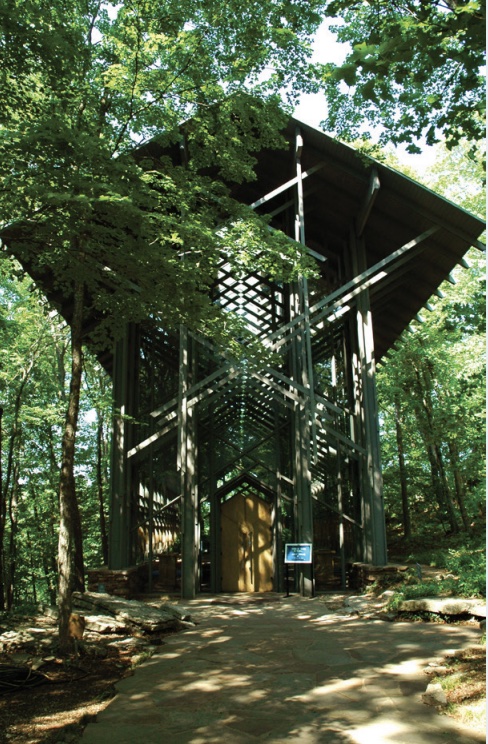

One example of an updated version is Thorncrown chapel, designed by E. Fay Jones (1921-2004, USA). Jones created a number of elegantly simple nondenominational chapels set into nature that let in diffuse light (Figures 68 and 69). A pupil of Frank Lloyd Wright, Jones was inspired by Wright’s principles of using simple, local materials to thoroughly integrate structure and setting. The most striking feature at Thorncrown, located in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, is the structure’s light airiness. The whole of the interior for each of Jones’s chapels is a small sanctuary that seems entirely at home in the forest.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Diagram Showing Lintel and Posts (Author: Corey Parson; Source: Original Work) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 2. Reconstructed Jōmon period (3000 BC) houses (Author: User “Qurren”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 3. Recreation of a Celtic Roundhouse (Author: User “FruitMonkey”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 4. Çatalhöyük at the Time of the First Excavations (Author: User “Omar hoftun”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 5. Old settlement Sjara Brae in Orkney Island, Scotland (Author: User “Chmee2”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 6. Inside a house at Skara Brae (Author: User “John Allan”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7. Model of Palace of Sargon at Khosrabad (Author: Internet Archive Book Images; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 8. Palace of Dur-Sharrukin (Author: Encyclopedia Britannica; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 9. Ostian Insula (Author: User “Nashvilleneighbor”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 10. Scene from Lararium, House of the Vettii, Pompeii (Author: User “Patricio.lorente”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 11. Diocletian’s Palace (Artist: Ernest Hébrard; Author: User “DIREKTOR”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 12. Palace of Aachen (Author: User “Aliesin”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 13. The throne of Charlemagne and the subsequent German Kings in Aachen Cathedral (Author: Bojin; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 14. Doge’s Palace and St. Mark’s Tower, Venice; Author: User “Rambling Traveler”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 15. Courtyard of Doge’s Palace (Author: User “Benh LIEU SONG”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 16. Himeji Castle, Japan (Author: User “Bernard Gagnon”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 17. The Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet (Author: User “Xiquinho”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 18. Chiswick House, London (Author: User “Patche99z”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 19. Monticello, Charlottesville, VA (Photographer: Matt Kozlowski; Author: User “Moofpocket”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 20. The Breakers, Vanderbilt’s mansion in Newport, RI (Author: User “Menuett”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 21. The library at The Breakers (Photographer: Matt Wade; Author: User “UpstateNYer”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 22. Fallingwater, Pennsylvania (Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright; Author: User “Daderot”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 23. Ziggurat of Ur, Iraq (Author: User “Hardnfast”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 24. Digital Rendering of the Ziggurat of Ur; Author: User “wikiwikiyarou”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 25. Drawing depicting the Basilica Ulpia, Rome (Artist: Julien Guadet; Author: User “Joris”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 26. Illustration Depicting the Basilica Ulpia; Author: Encyclopedia Britannica; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 27. National Mall and Washington Monument, Washington, DC (Author: User “Christoph Radtke”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 28. Theatre of Epidaurus (Author: User “Olecorre”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 29. Colosseum in Rome (Author: User “Andreas Tille”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 30. Wawadit’la, also known as Mungo Martin House, a Kwakwaka’wakw “big house”, with heraldic pole (Artist: Chief Mungo Martin; Author: Ryan Bushby; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 31. Whare at Waitangi Treaty House site (Author: User “Andy king50”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 32. Waitangi in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand (Author: Phil Whitehouse; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 33. Church of the Holy Apostles and Museum of Ancient Agora (Author: User “A.Savin”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 34. Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building, Chicago, IL (Author: User “Beyond My Ken”; Source: Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 35. The northwest entrance to the Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building (Author: User “Beyond My Ken”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 36. The Austrian Postal Savings Bank in Vienna, Austria (Author: User “Extrawurst”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 37. The Top of the Chrysler Building, New York City, NY (Author: User “Leena Hietanen”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 38. Petronas Twin Towers, Malaysia (Author: User “Morio”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 39. Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, CA (Author: John O’Neill; Source: Wikimedia Commons; License: GFDL).

- Figure 40. Rendering of the Giza Pyramid Complex, Egypt (Author: User “MesserWoland”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 41. Giza Pyramids (Author: Ricardo Liberato; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 42. Temple of Horus, Edfu (Author: User “ljanderson977”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 43. Inside the Edfu Temple (Author: User “Than217”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 44. Temple of Hephaestus, Athens (Author: User “sailko”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 45. The Acropolis of Athens, Greece (Author: User “Salonica84”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 46. The Parthenon, Athens, Greece; Author: Steve Swayne; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 47. The Pantheon, Rome, Italy (Author: Roberta Dragan; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 48. Interior of the Pantheon, Rome (Artist: Giovanni Paolo Panini; Author: Google Cultural Institute; Source: Wikimedia Commons License) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 49. Cross-section of the Pantheon in Rome (Author: User “Cmglee”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 50. Lomas Rishi Cave (Author: User “Neilsatyam”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 51. Brihadeshwara Temple, India (Author: User “Abhikanil”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 52. Sanchi Stupa, Madhya Pradesh (Author: User “Ekabhishek”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 53. Sultan Ahmed Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey (Author: User “Dersaadet”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 54. Diagram of old St. Peter’s Basilica (Author: User “Locutus Borg”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 55. Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Italy (Author: Angela Rosaria; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 56. Drawing and reconstruction of the Constantinian Basilica, Rome (Artist: H. W. Brewer; Author: User “Lusitana”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 57. Floor plan of Aachen Chapel (Artist: Georg Dehio; Author: User “Fb78”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 58. Floor plan of Amiens Cathedral (Artist: Georg Dehio; Author: User “Mattis”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 59. Basilica of St. Denis (Author: User “Ordifana75”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 60. Roman Arch/Gothic Arch Diagram (Author: Jeffrey LeMieux; Source: Original Work) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 61. Diagram of flying buttress of the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Amiens (Author: User “BuzzWikimedia”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 62. Bourges Cathedral (Author: User “sybarite48”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 63. Reims Cathedral, France (Author: Magnus Manske; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 64. Ambulatory of the Basilica of St. Denis (Author: User “Beckstet”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 65. Martyrs, Chartres Cathedral (Author: User “Ttaylor”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 66. Central tympanum of the Royal portal of Chartres Cathedral (Author: Guillaume Piolle; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 67. Nave of the Salisbury Cathedral, Wiltshire, UK (Author: User “Diliff”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 68. Thorncrown Chapel (Architect: E. Fay Jones; Author: Clinton Steeds; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 69. Inside the Thorncrown Chapel (Architect: E. Fay Jones; Author: User “Bobak”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Art: Design, Context, and Meaning. Authored by: Sachant, Pamela; Blood, Peggy; LeMieux, Jeffery; and Tekippe, Rita. Retrieved from: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-textbooks/3. Project: Fine Arts Open Textbooks. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike