Chapter 4.5: Masks and Ritual Behavior

Masks are found in all cultures throughout history. Early human cultures were primarily nomadic, so the portability of masks and other ritual objects may have been an important feature of their design and partly why they are so prevalent. Masks and the rituals in which they function may have been among the earliest ways in which humans acknowledged the objects and forces of nature as spirits or conscious beings.

The design of a mask is determined by its functions, and these functions are determined by the religious worldview of the culture in which they are made. In animist cultures, the forces of nature, objects, and animals are all thought to have spirits or essences. Rituals are performed that are aimed to please or guide these spirits in the hope that they will bring good fortune or that will help the culture avoid calamity.

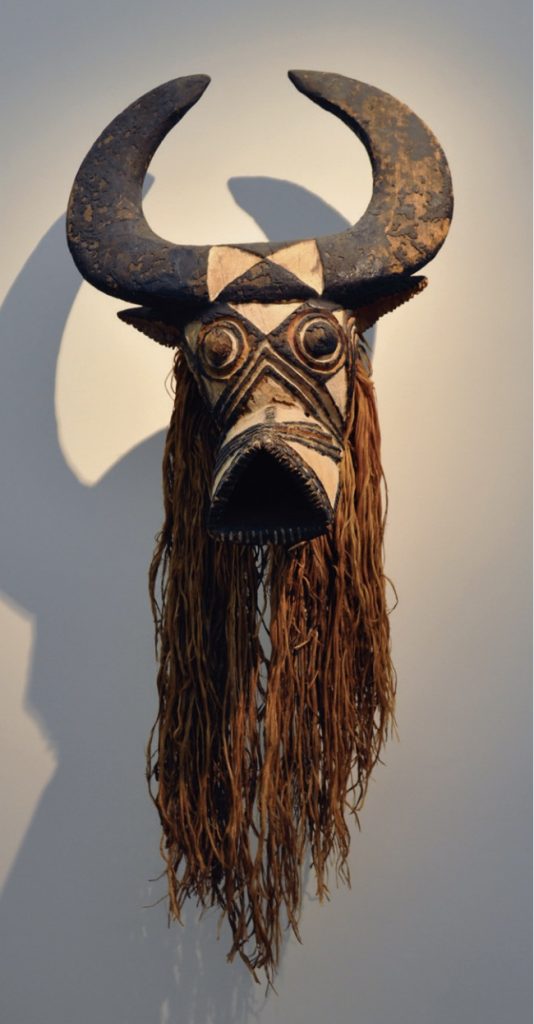

Contemporary African tribal rituals generally center on a number of life issues: birth, puberty, courtship and marriage, the harvest, the hunt, illness, royalty, death, and ancestors. In Burkina Faso, animal masks enter the community to purify its members and protect them from harm (Figure 1). In Nigeria, Yoruba Egungun, or masquerades, involve both masks and costumes (Figure 2). Costumes are made from layers of cloth chosen not only to demonstrate the family’s wealth and status, but also to connect the wearer to the spirits of ancestors who return to the community to advise and to punish wrongdoing. Once completely concealed, the wearer is possessed by and assumes the power of the ancestor through dance: as the pieces of cloth lift, they bestow blessings.

Due to a generally harsh climate not conducive to agriculture, Inuit cultures located in the Arctic regions of North America subsisted mainly on fish and other sea-dwelling animals, including whales. Early twentieth-century explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen asked his guide, an Inuit shaman, about Inuit religious belief. His response was that “we don’t believe, we fear.”

While it is a myth that Inuit elders were sent off into the wild to die (elders were and still are highly valued members of the tribe), many of the totemic and mask images of this culture are warnings against the dangers of making bad choices in a cold, harsh, and unforgiving environment. In this circa 1890 image, a Yupik (Eskimo) shaman exorcises evil spirits from a young boy; note the complex mask and large claws (Figure 3).

Mardi Gras, which is French for “Fat Tuesday,” is the day of Christian celebrations immediately before Ash Wednesday. Today, it is commonly considered the season of festivals, or carnivals, extending from Epiphany (Three Kings’ Day, when the Magi attested to the infant Christ’s divinity) on January 6 each year to the actual day of Mardi Gras, that is, the day before Lent begins. Originally associated with pagan rites of spring—the renewal of life and fertility—Mardi Gras dates back as a Christian rite to the Middle Ages in Europe when people ate as plentifully as they were able before the fasting and lean eating that took place during Lent. The associated festivities were a time to ignore normal standards of behavior and celebrate the excesses of life. Often dressed in masks and costumes as a means of casting aside one’s identity and social restrictions, the carnivals of Mardi Gras allowed a sense of freedom rarely known in societies that upheld a strict social hierarchy (Figures 4 and 5). We could discuss many more such visual experiences in the context of spiritual and philosophical ideas about the artistic expressions we devise to reflect our beliefs about mortality and immortality and how we connect these notions for ourselves. Suffice it to say that we can stay aware of the pervasive nature of art and visual experience in reflecting them.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Mask of Burkina Faso (Author: Andrea Praefcake; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 2. Yoruba Egungun Dance Costume (Author: User “Ngc15”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 3. Eskimo Medicine Man (Photographer: Frank G. Carpenter; Author: User “Yksin”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 4. Havré (Belgium), chaussée du Roeulx – The Gilles (Author: Jean-Pol GRANDMONT; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 5. Mardi Gras in Binche, Belgium (Author: User “Marie-Claire”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Art: Design, Context, and Meaning. Authored by: Sachant, Pamela; Blood, Peggy; LeMieux, Jeffery; and Tekippe, Rita. Retrieved from: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-textbooks/3. Project: Fine Arts Open Textbooks. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike