Chapter 4.4: The Sacred Interior

Sacred interior spaces offer several advantages over exterior sites such as platforms and gateways. In particular, they offer controlled access to the ritual space, for example, as we saw with complexes such as the Temple of Horus at Edfu (see Figure 3 in 3.12 Worship) and the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, Greece (see Figure 5 in 3.12 Worship), and they permit a new level of control over who is admitted. The nature of an interior space may also act as a metaphor for a personal encounter with the sacred within oneself.

We have noted that architectural forms have often been adopted and adapted according to the ways they serve group or congregational needs. Many religious centers meet a variety of purposes and needs, so they might include spaces or separate buildings for schools, meeting rooms, and any type of subsidiary accommodations. We will look, however, primarily at the basic distinctions among architectural forms that articulate and address the ritual and practical needs of the group.

It should be added that many practices are personal and individual and so may not require any sort of separate building; some may use a space within another sort of building or a room or corner within the home. Also, many rituals have been conceived as addressing a natural setting, such as an open field, a sacred grove of trees, a grotto or cave, or a specific spring, lake, or seaside spot (Figure 1).

Some of the basic features within many churches and temples reflect these notions. Although there are many exceptions, the layout of a structure most often relates to the four directions of the compass and the sites of most sacred precincts address the rising and setting of the sun. Altars are usually placed in the east. Over time, some adaptations have been made to accommodate other considerations; for example, a church or temple might be situated near a sacred mountain or a place where a miraculous occurrence took place. With these ideas in mind, we will briefly survey a few important types and features.

Features and Forms

Innumerable symbolic features are associated with worship; a few stand out as basic to identification of a building or site associated with a specific belief system. We quickly recognize and identify the distinctive implications of a steeple (church tower and spire) or a minaret, or the form of a stupa or pagoda, and we can sometimes discern how these and other such expressions came into use and accrued significance (Figures 2 and 3).

As discussed in Gallery V: Form in Architecture, the Islamic minaret was developed as a tower associated with a mosque that was used primarily to issue the call to prayer (and also to help ventilate the building). In the past, the imam, or prayer leader, charged with the ritual task would climb to its summit and intone the adhan five times each day, making the call in all directions so that the surrounding community would be notified; now, electronic speaker systems achieve this function. But the minaret has other implications and uses, as well (Figure 4). It has become a striking visual symbol of the very presence of the mosque and of Islam’s presence in the community; over time, many mosque complex designs have incorporated multiple minarets—most often four, with one at each corner of the main structure. The visual significance may have been further accentuated to rival the Christian presence of a nearby steeple or bell tower.

The bell tower has been used similarly to announce the onset of Christian services by ringing at specific times. Public clocks are sometimes added, with the function of noting the time, ringing or chiming a tune on the hour, the half hour, or the quarter hour. Because churches were often community centers, the bells could also give public notice of celebration, mourning, or warnings of emergency like fire. In the Middle Ages, the control of the bell ringing was sometimes a political issue, especially as urban communities developed governments and sought independence from local churches in certain ways. At Tournai, Belgium, such struggles notably led to a sort of visual combat of towers on the town skyline. The city’s civic leaders there were granted the right to control the bell ringing for community notices and built a separate tower away from the church located on the town square. The Church countered by renovating the church building to include four bell towers, seeking thereby to assert its own rights to identify itself with the task (Figure 5).

The steeple or bell tower visually implies a Christian presence and is generally part of the church building, usually on the façade. Over time, builders have added multiple towers, as they did at Tournai and elsewhere. Doing so emphasized the width of the façade, or other parts of the building, such as the transept, the “arms” in a Latin cross plan church, or the crossing, where the “arms” meet. For example, at Lincoln Cathedral in England, towers are placed at either side of the façade and another marks the crossing (Figure 6). Some steeples and towers associated with Christian use, however, have been erected independently of other buildings. For example, the Campanile, or bell-tower, by Giotto in Florence follows the Italian tradition of erecting the tower adjacent to the church (Figure 7).

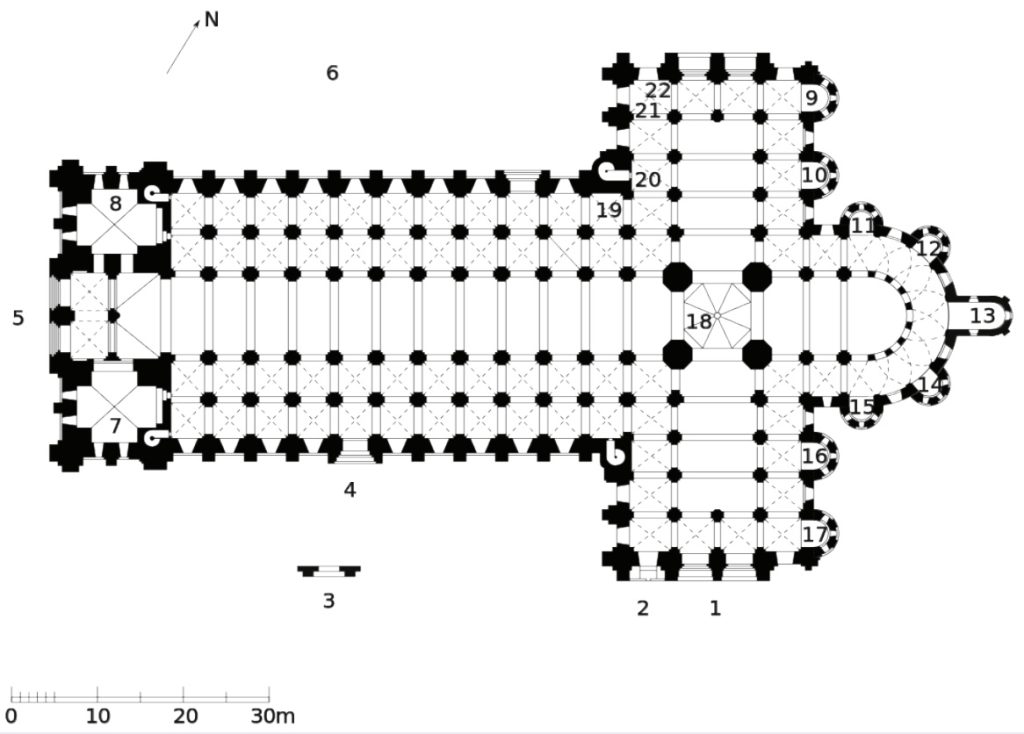

More specific features of church and stupa structures, among others, include space within or outside for circumambulating, walking around a sacred object. In medieval churches that featured display of relics and accommodated pilgrim visitation, the ambulatory might be altered to allow visitors to walk around a ring or succession of chapels at the end of the church where the apse was located (Figure 8). As referred to in Gallery V: Form in Architecture, at the Sanchi Stupa, provisions were made for the devotee to walk around the fence surrounding the stupa, then enter one of the gateways and circumambulate the mound on the ground level, then climb the stairs and circumambulate again on a walkway attached to its exterior surface (Great Stupa at Sanchi). Since the stupa is an earthen mound faced with masonry, it has no interior space accessible to the practitioner and all of the rituals are accomplished outside.

The provisions for making an offering of animals ritually slain for the deity can be seen in the ruins of the Anu or White Temple in Uruk (c. 3,000 BCE), today Iraq, which stood atop the ziggurat there (The White Temple floorplan; Temple and Ziggurat). The sanctuary chamber included a large altar table with channels along a sloped ditch to carry away the blood and other fluids resulting from the ritual sacrifice. Other types of sacrificial altars were provided for fire rituals that involved making offerings to a deity of an animal, grain, oil, or other substances, as can be seen in this Roman relief depiction of the sacrifice of a bull (Figure 9). Some of these altars were part of temple complexes, while others were found in homes and used for private devotions. Larger ritual fires are also part of the practices among some sects and are still in use; bonfires are a related practice.

Ritual ablutions, or cleansings, also have artistic accommodations in the forms of fountains and pools, which were once a standard part of Christian atrium courtyards that marked the entryways to churches and are frequently provided in courtyards for mosques (Islamic Pre-Prayer Ablution Fountain in Kairaouine Mosque Courtyard in Fes, Morocco). Vestiges are found in holy water fonts that still stand at portals to Catholic churches, where the practitioner dips the fingers and makes the sign of the cross. Also related are baptismal fonts or tanks used for the ritual cleansing, which, along with other ceremonial rites, signifies the entry into some faiths (Figure 10). Another type of symbolic liturgical furniture that appears in many worship contexts and is given considerable artistic attention is the pulpit, or minbar, as is it called in Islamic centers. It is the site of preaching, reading scriptures, and other addresses to congregations, and is, sometimes, very elaborately adorned (Figures 11 and 12).

Sculptural and Painted Expressions of Belief

Beyond the types of symbolic features and forms we have explored, there exists a tremendous variety of objects expressing common or personal belief and devotions. In many instances, they adorn temples, synagogues, and churches; at other times, they were designed to be used in private or family settings. Even the sects with the most austere attitudes about the use of art, such as the Shakers, have a design aesthetic that is related to the belief system of finding creative solutions in the functionality of the form (Figure 13). A lot of artistic efforts have been applied to religious expression, often entailing the notion that the most lavish and sumptuous goods should be provided for these purposes.

Sculptures, paintings, drawing, prints, film, video, performance art, visual demonstrations, all have been brought into service in this regard. They might vary as to whether they embody a point of doctrine or a shared tenet, or express a personal veneration for a deity or holy personage, or offer a viewpoint about exuberance or restraint; regardless, they have abounded. Often, they also epitomize the sentiment of a cultural moment in a particular place or the development of a particular line of thought in theology, philosophy, or devotional practice.

An example is the elegant and graceful Bodhisattva Guanyin, a spiritual figure of compassion and mercy, created in China in the eleventh or twelfth centuries during the Liao Dynasty (907-1125) (Figure 14). The sculpture acts as a compassionate guide for the Buddhist devotee who would look to such an elevated being for loving guidance on the spiritual journey. The ideas of patron saints or dedicated intercessors like the Virgin Mary were popular in the West, as well, especially during the Middle Ages, an era when great riches were often lavished on images of veneration for these spiritually accomplished models of sanctity. The graceful Virgin of Jeanne d’Evreux was a gift in the early twelfth century from the French queen to the Abbey of Saint-Denis, the site for royal burial at the time (Figure 15). The young mother, playfully engaged with her divine infant son, was rendered with striking and inspiring emotional effect.

In Christian churches of the Middle Ages, and for some denominations today, the sculptural embellishment of the interior not only showed the respect of believers but also provided considerable food for devotional thought, often in the form of Bible stories, tales of the saints, and theological ruminations. Such was the case at the French Romanesque Vézelay Abbey (1096-1150) (Figure 16). The tympanum above the portal contains a relief sculpture by Gislebertus depicting the Last Judgment, with Christ sitting in the center (Figures 17 and 18). The capitals on the piers in the interior have lively depictions of Old Testament tales such as Jacob and the Angel, and other scenes such as the Conversion of St. Eustace, a Roman general who while hunting saw a vision of a crucifix between a stag’s antlers and adopted Christianity (Figures 19 and 20). These are all told through delightful, puppet-like Romanesque figural forms. Visual stories such as these were meant to reinforce the importance of remaining true to God despite challenges to their faith in this lifetime.

Ritual and Devotional Objects

In devotional centers where the philosophical or religious beliefs allow the use of figural imagery, the use of cult statues and other images of deities or persons associated with the ideology are important focal points for worshippers. Some, like the cross, are essential statements; others play subsidiary roles, designed for amplifying or enhancing the spiritual experience and providing additional opportunities for contemplation or stimulus of devotional response. As we have noted, Buddhist and Hindu temple complexes often have a great array of portrayals of deities and/or spiritual leaders, as befits polytheistic religions. Part of the complaint of the Protestant revolt was that Christian churches had become too similar in spirit to polytheistic cults, with the wide selection of saints comprising a system that seemed no longer sufficiently focused on the central singular God. Part of the effect, in artistic terms, was that the decoration of many Protestant churches changed character—as well as liturgical focus—eliminating many of the lavish accouterments that had accrued around Catholic ritual.

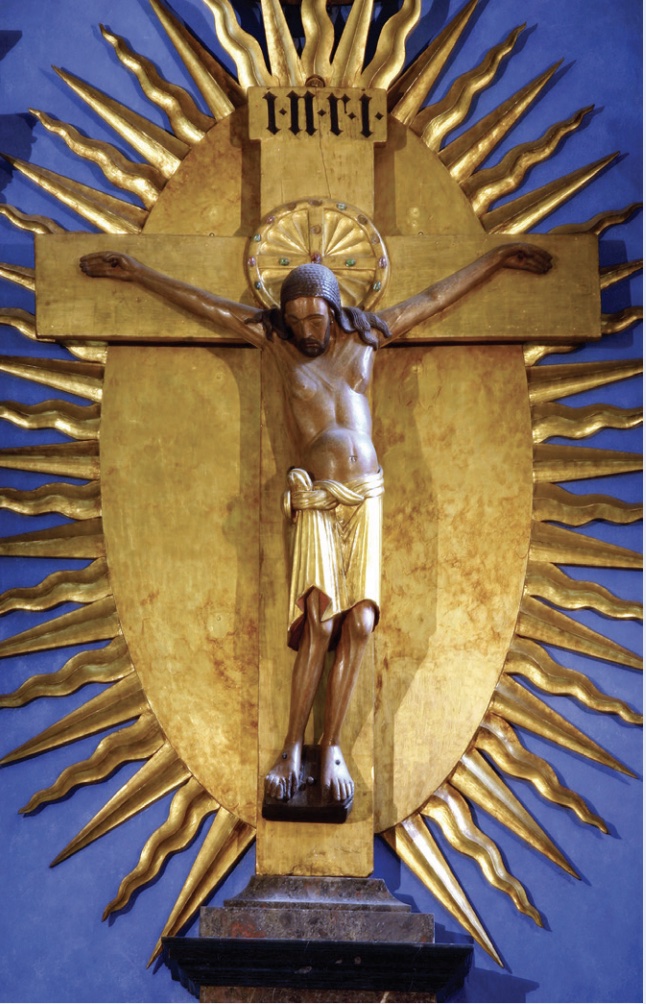

While few general rules exist for Christian decoration, the Catholic churches usually have a large and prominent crucifix above the main altar where the Mass/Eucharist, the primary religious ritual for Catholics, is celebrated; Protestant sites are more likely to have a plainer cross or none at all, and are unlikely to have an altar. Throughout the ages, the character of the crucifix has seen tremendous variation, from an expression of the extreme suffering of Christ to a much more iconic expression of the belief behind the symbol. Between the time of Christianity’s legitimization in 313 CE and the tenth century, for example, representations of Christ on the cross generally showed him as alive, having gloriously defied death. Crosses also varied considerably in scale. The Gero Crucifix (c. 965-970), now placed over a side altar in Cologne Cathedral, Germany, compared to others of its era was very large at six feet, two inches, and was considered to be provocative in eliciting contemplation of the suffering of Christ (Figure 21). Over the next several centuries, depictions of Christ on the cross in northern Europe would increasingly emphasize the agony of the human being in the throes of death, as opposed to his everlasting triumph, in ever more graphic portrayals of the event central to Catholic worship and to the liturgy of the Mass (Figure 22). The range of emotional content in Christian imagery is vast and ever changing. This diversity is a typical characteristic for objects that are related to devotional use, as the nature of active faith is to grow and change, ever producing fresh new expression.

The variety of liturgical equipment that was conceived for Christian ritual over the centuries provided great outlet for inventiveness. While some versions of ritual objects were simple and utilitarian in design, others clearly spurred flights of great fancy and flair. An important symbolic and functional object in all worship centers is the candlestick and a tremendous variety of these were created. One of the most elaborate was the enormous seven branched candelabra cast of gem studded bronze and covered with a mass of imagery of saints, plants, animals, and angels, with the whole immense and tangled array supported on four large dragon-form feet (Duomo Milano – Candelabro Trivulzio; Candelabro Trivulzio base detail). The complexity of the iconography, as well the intricacy of the work, is befuddling. Candleholders were not simply basic pieces of equipment, but also carriers of implications for the spiritual quest and the nature of religious inspiration, at least in part based on the symbolism of light as a representation of the Holy Spirit, purity, and peace.

Service objects for the altar table also received a great deal of attention, respect, and their fair share of artistic ingenuity. The chalice of Doña Urraca, from Spain, exemplifies spolia, the re-use of precious objects and materials from the past (Figure 23). As daughter and sister to kings, Doña Urraca oversaw monasteries and made provisions for their liturgies with lavish equipment. Made up of two antique onyx vessels for the base and cup, the chalice was fashioned with gem-studded bands and inscribed as a gift from Doña Urraca to the palace chapel in Léon, Spain. An ivory situla, or small bucket, is another liturgical object, used for sprinkling holy water in blessing at the Mass and other rituals, accomplished by dipping a sprinkler or a spray of leaves or straw into the vessel and flicking the water across the crowd (Figure 24). This example is finely carved out of ivory with scenes from the life of Christ and supplied with bands and inlay of gilt copper. Additional liturgical equipment includes vestments; these often have received great attention, as well (Figure 25). This fourteenth century example from England is of velvet embroidered with silk, metal thread, and seed pearls that ornament scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary.

Special attention was also paid to books of Scriptures, as well as those that were used for the Mass and other ceremonies. In the Middle Ages, the pages of books had to be created as manuscripts on parchment or vellum, as we have observed before; they were frequently supplied with lavish and showy covers, particularly those that might be used by important people or for important occasions. The commissioning of such was another deep and significant expression of faith due to the sacred writings they contained, the value of all liturgical equipment, and the merit accrued by donating riches for spiritual purposes.

The front and back covers of the Lindau Book Gospels were created at two different times and places with somewhat different design ideas (Front Cover of the Lindau Gospels; Back Cover of the Lindau Gospels). The front cover (c. 880 CE), which features a crucifix motif of the victorious Christ in gold repoussé, is further embellished with fluttering angels and an extraordinary encrustation of gems set with high prongs. The back cover dates to a century earlier and is thought to have been made for another (lost) manuscript. It is flatter, with engraved and enameled designs in the Hiberno-Saxon or insular style, which originated in the British Isles around 600 CE. The intricate serpentine and geometric patterns are similar to those found on the delicately crafted gold and cloisonné objects at the Sutton Hoo royal burial site in England (see Figures 8 and 9 in 5.5 Symbolism and Iconography in Module 3).

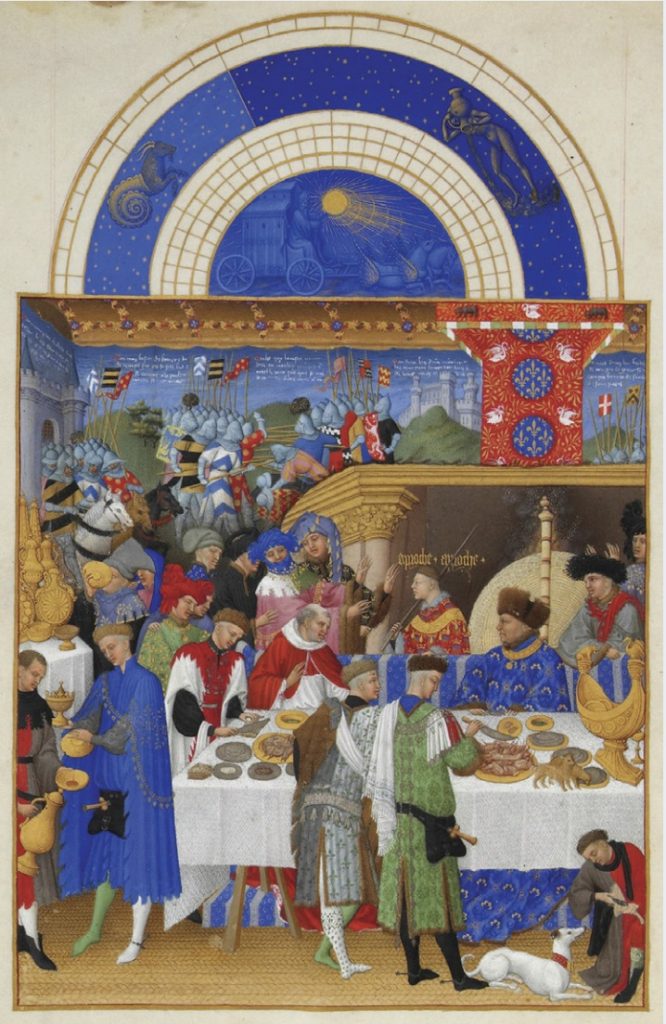

The contents of such books also often warranted rich illumination, or illustration, as we see in the prayer book or book of hours called the Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (Figure 26). It was created by the Limbourg Brothers (Herman, Paul, and Johan, active 1402-1416, Netherlands) for John, Duke of Berry, a French prince. Throughout its heavily illustrated pages or leaves, it is brightly colored, carefully inscribed, and replete with depictions of the Duke and of his many architectural and land holdings. It is well known for its calendar pages that depict activities associated with the changing seasons of the year, such as this scene of January showing the Duke seated in resplendent blue to the right at a sumptuous feast (Figure 27).

A significant visual spiritual event is the ritual creation of a sand mandala, often performed for a specific occasion by a group of Tibetan Buddhist monks, although there are other spiritual and cultural groups that create related works (Figure 28). To systematically build a complex mandala involves a carefully planned and meticulously executed approach and one that has very specific pictorial implications. Basically, a diagram of the Buddhist conception of the universe, mandalas might vary in expression of particular beliefs, teachings, or purposes. The process takes up to several weeks; surprisingly, at its completion, it is destroyed and ritually discarded, perhaps in a fire or a lake, to symbolize the fleeting nature of the material world. An impressive and colorful spectacle to witness, it is accompanied by additional sensual stimulation from the sounds of chanting and the scraping of the colors for the design, as well as the fragrance of flowers and incense.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Nanzen-ji garden, Kyoto (Artist: Musō Soseki; Author: User “PlusMinus”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 2. Church of the Covenant (Author: User “Fcb981”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 3. Phoenix Hall (Artist: Musō Soseki; Author: User “うぃき野郎”; Source: Wikimedia Commons; License) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 4. Minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia (Author: Keith Roper; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 5. Tournai, Belgium (Author: Jean-Pol GRANDMONT; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 6. Washington National Cathedral (Author: Carol M. Highsmith; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 7. Giotto’s Campanile (Author: Julie Anne Workman; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 8. Floor plan of St. Sernin (Author: User “JMaxR”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 9. Relief of a sacrificial altar (Author: Wolfgang Sauber; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 10. A Romanesque baptismal font from Grötlingbo Church, Sweden (Artist: Master Sigraf; Author: User “Bilsenbatten”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 11. Baroque pulpit in the Amiens Cathedral, France (Author: User “Vassil”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 12. Amr Ibn al-Aas Mosque (Cairo) (Author: User “Protious”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 13. Rocker in the Shaker Village at Pleasant Hill (Author: User “Carl Wycoff”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 14. Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara (Guanshiyin), Shanxi Province, China (Author: Rebessa Arnett; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 15. Virgin and Child of Jeanne d’Evreux (Author: Ludwig Schneider; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 16. The nave of Vézelay Abbey (Author: Francis Vérillon; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 17. The central portal of Vézelay Abbey (Author: User “Vassil”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 18. Lower Compartments Detail, Vézelay Abbey (Author: User “Vassil”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 19. Reliefs in Vézelay Abbey (Author: User “Vassil”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 20. Reliefs in Vézelay Abbey (Author: User “Vassil”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 21. The Gero Crucifix (Author: User “Elya”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 22. Pietà (Source: Met Museum; License: OASC).

- Figure 23. Replica of the Chalice of Doña Urraca (Artist: User “Locutus Borg”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 24. Situla (Bucket for Holy Water) (Source: Met Museum; License: OASC).

- Figure 25. Chasuble (Opus Anglicanum) (Source: Met Museum; License: OASC)

- Figure 26. The Nativity (Artist: Limbourg Brothers; Author: User “Petrusbarbygere”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 27. January (Artist: Limbourg Brothers; Author: User “Petrusbarbygere”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 28. Mandala (Author: User “GgvlaD”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Art: Design, Context, and Meaning. Authored by: Sachant, Pamela; Blood, Peggy; LeMieux, Jeffery; and Tekippe, Rita. Retrieved from: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-textbooks/3. Project: Fine Arts Open Textbooks. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike