5 Chapter 4.2: Imagery of War

Considering the potential for art to give expressive form to ideas and emotions, it is not surprising that art has often been used to present a wide range of messages about war, one of the most dramatic of human events. All forms of art have been used for documenting war, stating reasons for supporting or opposing it, and showing reflections about its meanings, implications, and effects. On a broader scale, all human activities, of course, may be occasions for people to criticize one another, to condemn ideas, ideals, and actions, to promote or oppose causes that express cultural, societal, or individual values. We will examine a number of works that are concerned with these issues in various ways.

Historical/Documentary

From the earliest times, artists have responded to issues of war and conquest and their implications for the cultures in which they took place. Often, the art appears to have been created to mark a moment of triumph and to interpret the conquest as a validation of a leader’s right to rule, established through the victory. Such was the case with the Palette of Narmer (Figure 1). On the two-sided palette are relief-carved depictions of the subjugation of the enemy by Egyptian King Narmer (also referred to as Menes)—under the watchful protection of the deities—and a procession of the King and his attendants toward the decapitated bodies of ten of the defeated. On the first side, Narmer wears the crown of Upper Egypt and on the reverse he wears the crown of Lower Egypt, symbolizing the union of the two regions under one ruler (c. 3,100-3,050 BCE). He is depicted far larger than both his enemies and his own men, showing the figures’ relative importance. Narmer is literally depicted as a powerful, firm, and resolute warrior who will be a strong and worthy leader.

Grand artistic depictions of rulers in battle have always been used to help form their reputations and to bolster the images of their good and wise rulership. Military success has long been equated, correctly or not, with political prowess. The heroic feats of Alexander the Great (r. 336- 323 BCE) at the Battle of Issus (333 BCE) with the powerful Persian King Darius III (r. 336-330 BCE) were portrayed in a Greek painting that no longer exists. Like much of Greek art, though, it was copied by the Romans, so we do have a mosaic version of the tumultuous battle that was created for the House of the Faun in Pompeii, Italy (Figure 2). This enormous depiction, although damaged and now incomplete, gives a lively, somewhat riotous account of the dramatic encounter of these two renowned warriors. Alexander can be seen to the left on his chestnut horse, staring with wide-eyed intensity at the fleeing Darius, who turns to look at his opponent with one arm extended as if pleading for mercy while the driver of his chariot whips the King’s horses into a frenzy of motion.

We should consider to what extent these accounts are documentary, based on factual records, and what we can discern that is propagandistic in purpose. In many eras, the glorification of heroes and heroic deeds in war was perhaps paramount, not only from a political and patriotic standpoint, but also because these were the values promoted as part of artistic training in academic settings (values that prevailed for most successful artists at least through the middle of the nineteenth century, when anti-academic rebellions began in art circles).

American heroism in war was certainly envisioned in these terms, as evidenced in Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill by John Trumbull (Figure 3). As discussed in Chapter 8 Art and Identity, Trumbull was an aide-de-camp to General George Washington. After witnessing Warren’s death in Boston, Trumbull was commissioned by Warren’s family to immortalize the event. The Battle of Bunker Hill took place in 1775, the first year of the American Revolutionary War. Although the colonialists were defeated, the British were stunned by their far greater number of casualties, boosting the morale of the young army. In his painting, Trumbull focused on the General’s tragic death as the colonial forces retreated, as well as the compassion of British major John Small, who held back one of his men as the soldier was about to bayonet Warren. Doing so, Trumbull could celebrate the heroism of the Americans while also acknowledging the honorable behavior of the enemy, an expectation in eighteenth-century codes of conduct during pitched battles.

Trumbull’s depiction of the battle scene is greatly romanticized: an historically accurate rendering of General Warren’s death was neither expected nor desired by viewers of the day. Many questions have been asked, as well, about the accuracy of the grand tableau by Emanuel Leutze (1816-1868, Germany, lived USA) of Washington Crossing the Delaware, a painting that is an iconic symbol of the American Revolutionary War and the first president of the United States (Figure 4). Leutze created the work in 1851, seventy-five years after the Battle of Trenton occurred in 1776. Far from attempting to reconstruct the scene as it took place, Leutze intended his work to be an evocation of a grand and inspirational event, dramatically pictured.

By the time Frederic Remington (1861-1909, USA) painted Charge of the Rough Riders in 1898, warfare and depictions of it were much different. Remington gives us the spirit of the fray—more down to earth, momentary, and rough and tumble (Figure 5). The implications are much less aggrandized and heroic, the viewer’s sense of the event much more intimate. And by the time of the World War I appearance of Gassed by John Singer Sargent (1858-1925, USA, lived England), we see a different tenor altogether (Figure 6). Here, we are privy to Sargent’s personal response to the deadly aspects of war, to the after-effects for the individuals who were each physically assaulted by poison mustard gas and are showing its ill effects as they were weakened, nauseated, and felled.

The changes in interpretation are due in part to those changes towards realism in art during the nineteenth century that we have explored. Also, they were heightened by the advent and evolution of photography, which had enhanced potential for documentation of actual conditions. But photography did not, by any means, always present the viewer with unvarnished truth, since it could, like painting, be manipulated in its effects. Nonetheless, the potential for a different view of war and its effects was ushered in with the advent of photography.

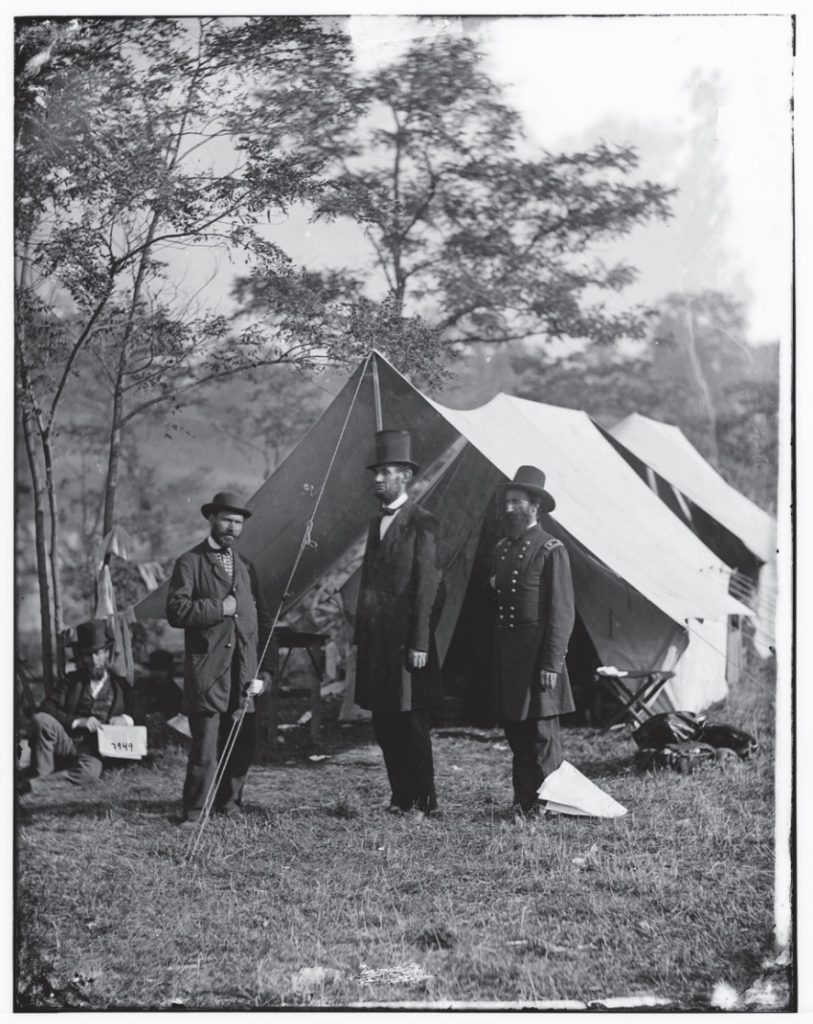

The American Civil War provided a venue for photographers to use the new medium in recording exactly what they were seeing, through the lens. But the processes were still not up to the task of capturing the actions, because equipment was cumbersome, and exposed photographic plates had to be developed on the spot in specially outfitted wagons. The result was that most of the photographs were of groups of dead bodies and battlefields laid waste, after the actual event (Figure 7). The sights were nonetheless sobering to the viewers who had never before been privy to views of the result of war on such a scale. Alexander Gardner (1821-1882, Scotland, lived USA) was one of a number of photographers who captured many battlefield scenes, as well as views of campsites and many other details of the deployments, including visits from such dignitaries as President Lincoln (Figure 8).

The potential for a more critical interpretation afforded by photography had in the past been taken at times, even though not as the norm. Notable examples come from several periods when artists responded to the horrors and agonies of war and injustice in various ways and created memorable interpretations that reveal their protests of conditions. In 1633, Jacques Callot (1592- 1635, France) created a suite of panoramic etchings that dramatize The Miseries of War (Figure 9). Francisco Goya’s monumental Third of May, 1808, painted in 1814, showed the fear and horror of an encounter between Napoleon’s troops and citizens of the town of Medina del Rio Seco, where 3,500 Spaniards lost their lives (Figure 10). Goya’s sympathies are clear in his presentation of a terrified white-shirted martyr-like figure facing a firing squad while in the midst of his equally horrified compatriots.

Similarly, Honoré Daumier dramatized the injustice of a night raid in the home of a working-class family in Paris during protests in 1834. Following a shot having been fired from a window in the building where twelve members of the Breffort family lived, soldiers stormed their apartment and killed them all. Six months later, Daumier created, a stark lithograph depicting helpless family members as they fell (Figure 11). Daumier had been jailed two years earlier, in 1832, for caricatures (portraits containing features or characteristics exaggerated for comic effect) he made ridiculing King Louis Phillipe I (r. 1830-1848). Immediately after the artist created Rue Transnonain, the street on which the Breffort family lived, the lithographic stones he used were confiscated by government officials and all copies of the print were destroyed. The following year, political caricatures were banned entirely. This indicates the power Daumier’s work was perceived as having and the danger it could hold for those in power.

As noted, the potential for a different view of war and its effects was ushered in with the advent of photography. The American Civil War in the 1860s provided a venue for photographers to use the new medium in recording exactly what they were seeing, through the lens. But the processes were still not up to the task of capturing the actions, because equipment was cumbersome and exposure times were still relatively long and slow. Alexander Gardner’s photographic corps created many after battle scenes as well as portraits of generals, the president, campsites, and many other details of the deployments (see Figures 8 and 9 in 5.5 Symbolism and Iconography in Module 3). The potential for capturing action and momentary pathos only increased from then on, and the capacity for documenting graphic events has been used widely ever since (see Figures 10, 11, 12, and 13 in 5.5 Symbolism and Iconography in Module 3). Compare the image of corpses being bulldozed and buried wholesale to the photos of Gardner and the previous painted glorifications of the battlefield.

Reflective/Reactionary and Anti-War

One of the most powerful anti-war statements ever painted was by Pablo Picasso, created in 1937 following the bombing of the town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. He was commissioned by the Spanish Republican Government to create a mural for that country’s pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris and, after learning of the attack, designed this poignant abstraction of symbolic and iconic motifs to express the horror of the event (Guernica, by Pablo Picasso, originally displayed at the Pavilion of the Spanish Republic at the Paris International Exposition, 1937). His knowledge of the details had been gleaned from newspaper reporting, so he elected to create the imagery in the graphic black, gray, and white of the photographs through which he learned of the bombing and its impact. His dramatic distortions of form convey the deep anguish and disgust that had been engendered in him, his fellow Spaniards, and the world.

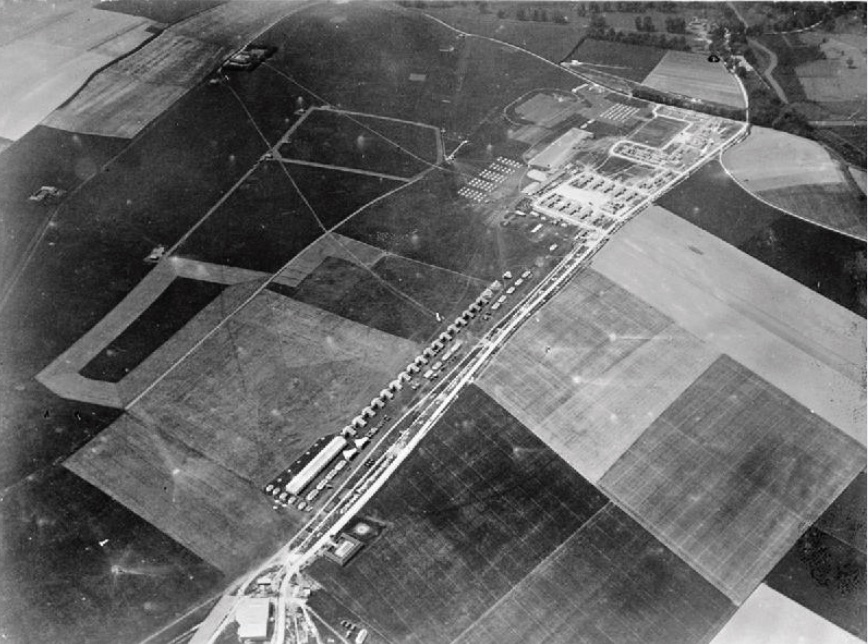

Over the course of the twentieth century, documentary photography was used not only to capture the brutal events of war, but also to broadcast moments of utter horror in such graphic ways that they have influenced public sentiment, sometimes turning opinion from support to outrage. By the time of World War I, technology permitted the reproduction of photographs in newspapers, which meant that the average citizen had far greater access to visual news of the war than in earlier conflicts. Some leaders, such as German Kaiser Wilhelm II (r. 1888-1918), were in favor of using photographs as a means of bolstering public support for the war, but others restricted photographers’ access and censored photographs, citing security concerns. Shortly before the beginning of World War I, the British Army was the first to realize the potential of photography for aerial reconnaissance, greatly expanding their research capabilities and troop maneuverability (Figure 12).

During World War II, American military and government agencies tremendously expanded the use of photography for purposes ranging from conducting espionage and assisting training, to recording atrocities and providing documentation (Figures 13 and 14). During the Vietnam War (USA involvement, 1955-1975), the American military gave unprecedented access to non-military reporters and photographers. As the war extended in the 1960s, far longer than the American people expected, images of conflict and suffering in the war-torn country began having an impact on public opinion. (Women and children crouch in a muddy canal as they take cover from intense Viet Cong fire, Horst Faas). By 1972, when Nick Ut (b. 1951, Vietnam, lives USA) photographed children fleeing their village after it was attacked with napalm, the tide had turned and many Americans no longer supported the Vietnam War. (Phan Thị Kim Phúc running down a road near Trảng Bàng, Vietnam, after a napalm bomb was dropped on the village of Trảng Bàng by a plane of the Vietnam Air Force, Huynh Cong Ut).

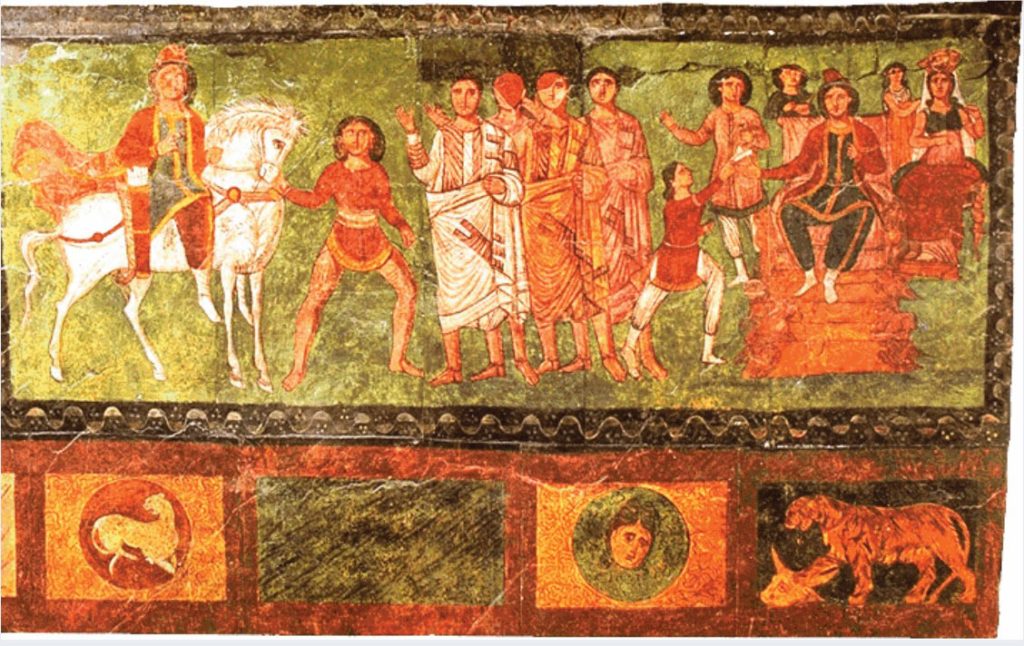

Prohibition or Destruction of Imagery: Iconoclasm

Controversy over imagery and its use, especially in sacred contexts, also has a long history. Debates on the topic have, at times, erupted into deep and bitter arguments. It has often been thought that, because of the Old Testament statements forbidding the use of idols, the Jewish religion has never allowed pictorial or figural art as part of its religious expression. More current findings, though, lead to the conclusion that the biblical statements were actually pointedly made at times against the real danger of idolatry, or the worship of idol images, rather than being a broad prohibition of images altogether. Dura-Europos was a military outpost in Syria held by the Romans 114-257 CE where the garrisoned soldiers obviously practiced a wide variety of religions. The site has a great number of different pagan temples, a Christian house church, and a Jewish synagogue, or house of worship, that is decorated with a great array of lively figural frescoes that depict Old Testament stories (Figure 15).

Early Buddhist art was, according to some, aniconic, or characterized by the avoidance of figural imagery that represented Sakyamuni Buddha, its fifth-century BCE founder. Others disagree. We have no examples of Buddhist art until the second century BCE, well after the death of Sakyamuni, probably because early works were of impermanent materials and have not endured. In the earliest we do have, the figure of the Buddha does not appear; rather, we see the seat where he achieved enlightenment and the Bodhi tree that shaded it (Figure 16). Scholars disagree as to whether the absence of the Buddha confirms a prohibition of showing his figure.

On the contrary, we do know there is a general aversion to the use of figural imagery in sacred uses in Islam, although it is not universally heeded. There is no specific prohibition in the Koran, the central sacred scripture for Islam; however, there are authoritative statements among the writings of the Hadith, the commentaries on the Koran that supplement its teachings. The rationale is that the creation of human and animal form is reserved for God and should not be an act of man. Thus, the decorations of mosques and related structures are usually accomplished with lavish linear scripts, embellished with arabesques and vegetal and floral motifs (Figure 17). The script is usually drawn from the Koran or is simple praise of Allah; this sort of design is often also applied to all sorts of goods and décor for the Muslim household (Figure 18).

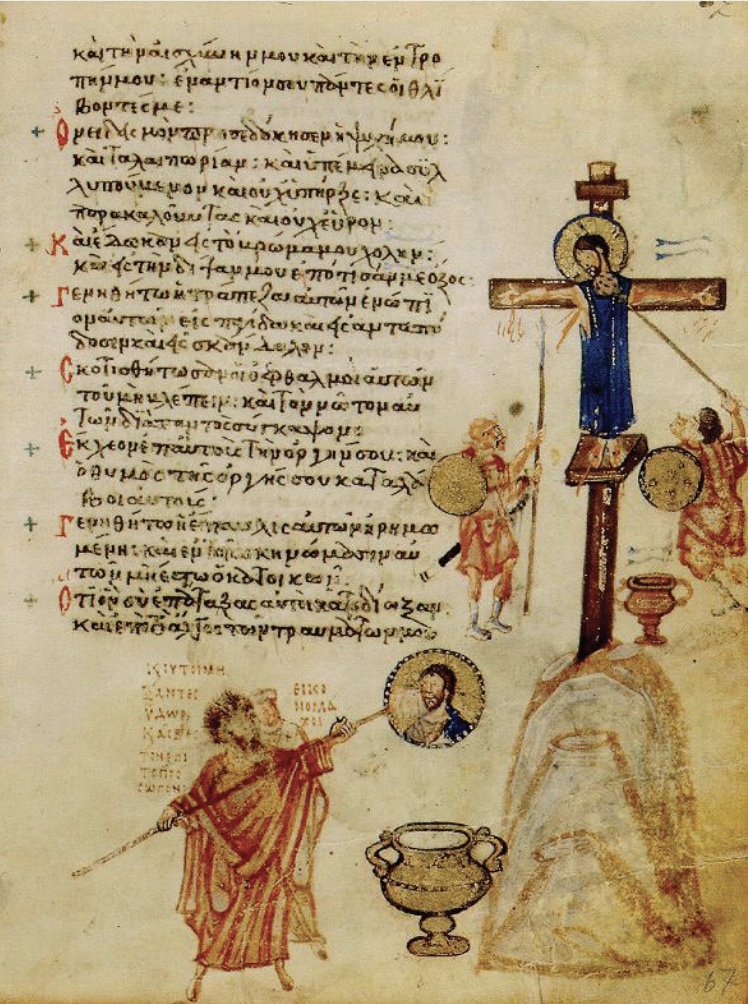

A dramatic example of the anti-imagery debate took place in the Byzantine Christian Church in the eighth and ninth centuries CE. Based on the perception of the biblical prohibition, an assault was mounted against all religious images, and much of the existing artwork was destroyed in an effort to eradicate what was considered an evil practice. The defenders of the use of imagery argued that the problem was not the images themselves, which could be positive aids to spiritual inspiration and religious devotion, but to their improper usage, which resulted in a sort of idolatry, akin to pagan idol worship. The images, according to proponents of their use, should be seen as tools, associated with understanding God and the saints, and as means of furthering the contemplation of Christian mysteries. Further, they argued, to obliterate existing images, to deface pictures and to destroy statues was to desecrate sacred things and, effectively, to disrespect the holy beings which they represented.

This notion was expressed in the mid-ninth-century Chludov Psalter with an illustration that equates the destruction of an icon with insulting Christ on the cross when he was forced to take gall (bile) and vinegar by the mocking Roman soldiers (Figure 19). The controversy was settled in 843 and the use of icons and imagery thrived thereafter. Unfortunately, very little of the religious artwork that was produced prior to this time survived for us to examine.

Other chapters in the debate over imagery open in later centuries. For some Christians, it was one point of disagreement leading to the Protestant Reformation that began in Wittenberg, Germany, in 1517. According to those protesting what they saw as abuses of power in the Roman Catholic Church, the proliferation of images of holy figures and stories from the Bible distracted the faithful from true worship: reading the word of God in the Bible. As new religious practices spread, there was a widespread removal of religious paintings and sculpture from all churches and public buildings (Figure 20). In the Wars of Religions that raged in many places in Europe (c. 1524-1648), the destruction of images was one of the violent forms of protest by angry crowds that railed against any and all prevailing practices and the powers they held responsible. A great many church portals (doors) were damaged by those who saw lopping off heads of sculptures above the doorways as a fitting expression of their anti-Church sentiment (Figure 21).

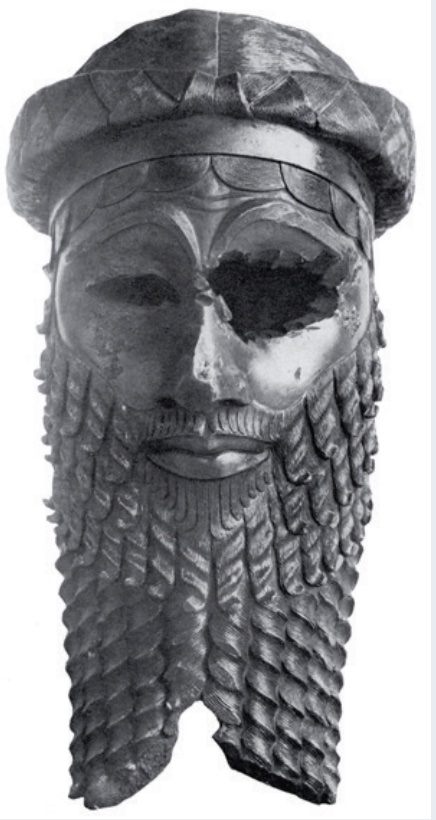

Throughout history, such destruction has certainly not been restricted to religious controversies. From very early examples, we know of what is likely purposeful defacement of ruler images that were made either in protest or as a sort of proclamation of defeat and superiority. The gouging out of the jeweled eyes in this bronze head of Assyrian King Sargon II might have been for theft of the precious materials, but it may also indicate conquest over the man himself (Figure 22). In recent times, we have seen the dramatic toppling in 2003 of the statue of Sadam Hussein in a public square in Baghdad, Iraq, as a symbolic overthrow of a despised and despotic ruler. (Figure 23). Further humiliation of him was clearly intended by the widespread publication of photos of captors picking lice from his head after his discovery in a spider hole.

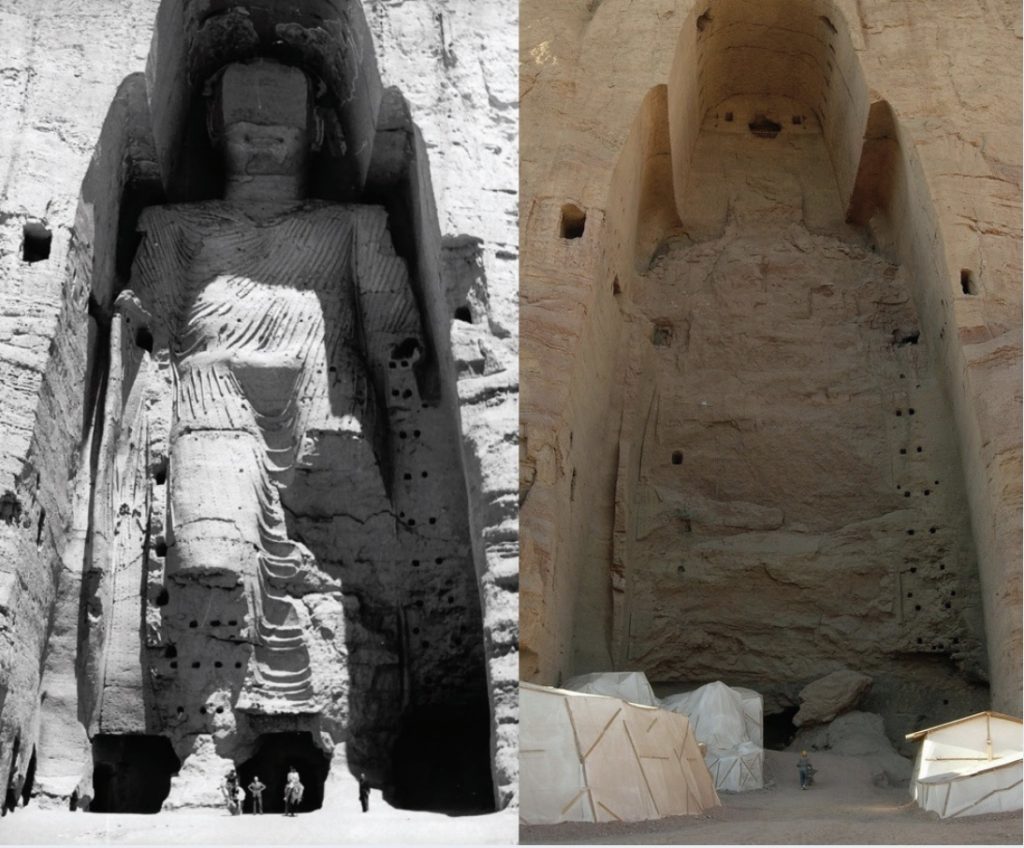

The power of such pointed symbolism in visual terms is employed to fight culture wars, as well. In Afghanistan, in 2001, the Taliban undertook to dynamite two colossal images of the Buddha dating to the sixth century CE that had been carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamyan valley of central Afghanistan (Figure 24). Arguments came from all over the world, pleading with them to preserve monuments that were considered part of the cultural heritage of humankind. Nonetheless, they completed their task, declaring it a duty to eliminate an image that violated their spiritual beliefs.

A similar scenario unfolded more recently, when ISIS militants went on a destructive campaign to destroy historically and culturally valued artwork in the Mosul Museum, Iraq, despite pleas from curators and art lovers around the globe. (Extremists used sledgehammers and power drills to smash ancient artifacts at a museum in the northern city of Mosul) This sort of protest is often made on a smaller scale, as well, when symbolic or iconic imagery is defaced or destroyed as a means of mocking its value to those who respect it, as with the Nazi symbols made on Jewish gravestones or the burning of the American flag (Desecrated Jewish gravestones) (Figure 25). All such incidents reinforce our understanding of the varieties of power that art and visual imagery can have.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Narmer Palette (Author: User “Nicolas Perrault III”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 2. Alexander Mosaic (Author: User “Berthold Werner”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 3. The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, June 17, 1775 (Artist: John Trumbull; Author: Boston Museum of Fine Arts; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 4. Washington Crossing the Delaware (Artist: Emanuel Leutze; Author: Google Cultural Institute; Source:; Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 5. Charge of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill (Artist: Frederic Remington; Author: User “Julius Morton”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 6. Gassed (Artist: John Singer Sargent; Author: User “DcoetzeeBot”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 7. Photograph of bodies on the battlefield of Antietam during the American Civil War (Photographer: Alexander Gardner; Author: User “Shauni”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 8. Photograph of Allan Pinkerton, President Abraham Lincoln, and Major General John A. McClernand (Photographer: Alexander Gardner; Author: User “Bobanny”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 9. The miseries of war; No. 11, “The Hanging” (Artist: Jacques Callot; Author: artgallery.nsw.gov.au; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 10. The Third of May (Artist: Francisco de Goya y Lucientes; Author: Prado in Google Earth; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 11. Rue Transnonain, le 15 Avril, 1834, Plate 24 of l’Association mensuelle (Artist: Honoré Daumier; Source: Met Museum; License: OASC).

- Figure 12. Aerial Photography Before the First World War (Artist: Laws F C V (Sgt); Author: User “Fae”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 13. Bones of anti-Nazi German women in the crematoriums in the German concentration camp at Weimar (Buchenwald), Germany (Photographer: Pfc. W. Chichersky; Author: User “Petrusbarbygere”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 14. Two enlisted men of the illfated U.S. Navy aircraft carrier LISCOME BAY, torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in the Gilbert Islands, are buried at sea from the deck of a (Coast Guard-manned assault transport.; Author: User “W.wolny”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 15. Part of the fresco at the Dura-Europos synagogue (Author: User “Udimu”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 16. Mara’s assault on the Buddha (Author: User “Gurubrahma”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 17. Mihrab of Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba (Author: User “Ingo Mehling”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 18. Seventeenth-Century Persian Bowl (Author: User “Udimu”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 19. Miniature from the 9thcentury Chludov Psalter with scene of iconoclasm. Iconoclasts John Grammaticus and Anthony I of Constantinople. (Author: User “Shakko”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 20. Iconoclasts in a church (Artist: Dirck van Delen; Author: User “BoH”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 21. 16th-century iconoclasm in the Protestant Reformation. Relief statues in St. Stevenskerk in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, were attacked and defaced in the Beeldenstorm. (Author: User “Ziko”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 22. Bronze head of a king, most likely Sargon of Akkad but possibly Naram-Sin. (Author: Iraqi Directorate; General of Antiquities; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 23. Statue of Saddam Hussein being toppled in Firdos Square after the US invasion of Iraq. (Photographer: U.S. military employee (Author: User “Ipankonin”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 24. The taller Buddha of Bamiyan before (left) and after destruction (right). (Author: User “Tsui”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 25. Desecration of the U.S. Flag by burning (Author: Jennifer Parr; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Art: Design, Context, and Meaning. Authored by: Sachant, Pamela; Blood, Peggy; LeMieux, Jeffery; and Tekippe, Rita. Retrieved from: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-textbooks/3. Project: Fine Arts Open Textbooks. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike