Chapter 13.6: Censorship

From “Censorship” by Barbara Kauffman from Grove Art Online (Oxford)

“Control of expression that is regarded as outside of and a threat to the religious, political, and social orthodoxy of the time. Throughout history, when governments and other powerful institutions of society have been fearful of the power of art to challenge the established order, they have sought to suppress the works of literature and art that appear decadent, disruptive, indecent, or immoral. Manifestations of the control of artistic expression are historically and culturally specific. Nevertheless, close consideration reveals recurring themes and issues. Awareness of the power of art has meant that censorship accompanies art’s practice and exhibition. According to Plato, ‘because art has the power to intensify and not just purge emotions, a “dramatic censor” must control the content and form of all artistic expression’. By extension, the artist is feared because of his or her ability to make revered things that, depending on the culture, may rival divine creation. Thus, censorship has been a two-edged sword that proscribes as well as prescribes. Long before the first official censors were established in Rome with the Lex Canuleia in 443 bc, prohibitions against and standards for the production of imagery were part of the Egyptian, Hindu, Hebrew, and Babylonian cultures. Plato praised Egyptian art as an instrument for preserving culture because ‘no painter or artist is allowed to innovate or to leave the traditional forms and invent new ones’ “(Laws II.656).

Plato’s distrust of the visual arts derived from the premise that representation can deceive by seeming real. In this regard, he urged that deceptions be avoided by the adoption of standardized canons. Such canons are a form of censorship since they prohibit or strongly discourage deviations from the norm. Indeed, the belief in norms or standards for art, whether legally explicit or culturally implicit, has been essential to the exercise of censorship. A canon can be used to determine the ‘appropriateness’ or ‘decency’ of a piece (Silk). A canon may reinforce the status quo; it may also embody trepidation about the ‘other,’ crucial to much censorship since recognition of the ‘other’ also threatens the status quo. Actual censorship should be distinguished from disinterested art criticism, although the distinction between criticism and censorship is not always clear. Reasons for rejection based on apparently neutral criteria, such as style, may often mask discrimination against the ‘other.’ For example, in 1994, the New York-based group Guerrilla Girls exposed in its newsletter Hot Flashes how collecting and exhibiting by museums discriminates against women (or the ‘other’). Censorship deprives the artist of access to an audience, and the public of access to the work of art as created. As such, censorship is the knot that binds power and knowledge. Fundamentally, censorship of art may be a means by which those in power seek to maintain power, and it continues to be based on ideological, moral, and aesthetic grounds.

Religious orthodoxies have often provided the parameters of what is or is not acceptable to be seen by an audience. The censorship of religious art, including the banning, destruction, or alteration of works, is roughly equated with the term Iconoclasm, for example, the battle waged by the Jews against any type of idolatry until the end of the 2nd century ad, and the iconoclastic controversies of the Byzantine empire (ad 726–843). Although the motivation of iconoclasm is complex, it almost always has a significant political dimension. Thus, in the Byzantine Empire, it was tied to a reassertion of imperial authority. The acts of the Second Council of Nicaea in AD 787 adopted rules and regulations to establish which holy images could be represented and how. Between the 13th and 15th centuries, images became important in the service of the Catholic Church. The second iconoclastic war in Europe began in the 14th century when the Reformation leaders used art as an excuse for attacking Rome. In 1536, the French theologian and reformer Calvin gave impetus to the Puritan ethic against art that already existed in the writings of St Augustine, Girolamo Savonarola, and other European religious reformers. As detailed in his Christianae religionis institutio (Basle, 1536), Calvin preached against two kinds of false art: art that is against Christ (the use of images in the Church) and art for art’s sake (art that exists only for enjoyment). The Catholic Church of the 16th century counter-attacked and reaffirmed the argument in favor of art as a visual aid for teaching the illiterate. Through the decrees of the Council of Trent (1563–83), art was put in the service of the Church, and its strict regulations and official pronouncements on the representation of images remained in force for another century.

Girolamo Savonarola was not as much opposed to the use of paintings in the service of religion as he was to indecent pictures and, especially, nudity. This trend was supported by church leaders for almost 200 years. Michelangelo was accused of showing too much nudity in a sacred work and of not following the regulations of the Council of Trent; in 1558, Pope Paul IV assigned Daniele da Volterra, a follower of Michelangelo, the job of placing ‘draperies’ over the problem sections of the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, Rome. Paolo Veronese was actually brought before the Tribunal of the Inquisition in 1573 to defend his Last Supper in the House of Simon (1573; Venice, Accad.) because the sense of realism in this painting was considered heresy. Veronese pleaded artistic license in his defense; he was given three months to change the painting. He changed only the title—to Feast in the House of Levi—which, surprisingly, satisfied the Inquisition because the Last Supper had taken place at Simon’s. In Russia, during the 16th century, Ivan the Terrible (reg 1547–84) promulgated rules affecting many issues, from icon painting to shaving, in an effort to effect strict social control, and a Church code proscribed secular materials in the arts.

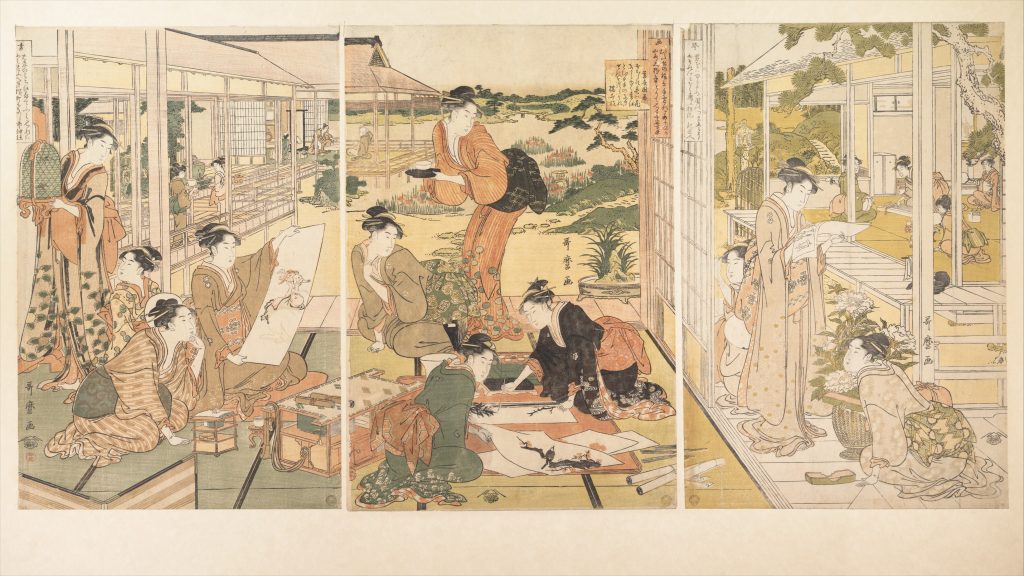

Politics and ideology play a role in every act of censorship. For example, in Japan, from the 18th century to the early 20th, public morality and the ‘proper’ way to depict the past and present preoccupied the ruling élite. Neo-Confucianism was employed ideologically, to dissimulate the effects of earlier temporal division. As a philosophy, it privileged the representation of the world as a totality and proposed that society, like nature, was a natural unity organized in a hierarchy. Neo-Confucianism promised to eliminate the destructive power of passion and desire. Ukiyo (‘floating world’) was the term used to describe the pleasure and entertainment districts of the lower, but often wealthy, popular, and merchant classes. These zones challenged the order of Neo-Confucianism’s morality. Since woodblock prints were mirrors of the ukiyo milieu, they also had to be strictly regulated. Such controls were justified as ways to maintain the existing Tokugawa social structure, to prevent intermingling of the social classes, and to promote moral order and decency. Edicts of the early 18th-century Edo magistrate banned three subjects in visual expression: pornography, Christianity, and the Tokugawa family. The latter was by far the most important. Any direct criticism or political satire of the government was prohibited. Artists and publishers both developed a complex language of veiled dissent to deal with the Tokugawa censorship laws, including changing names and providing a fictitious setting in another era. A parallel existed in the censorship practiced by Louis-Philippe, King of France, after the establishment of the July Monarchy (1830), when prints required official approval prior to publication. Honoré Daumier was charged and brought to trial for ‘crimes against the person of the King’ and the law against ‘representation of the King’ for his caricature of the monarch as Rabelais’s Gargantua, published in La Caricature (15 Dec 1831). Political caricature was forbidden in France from 1835 to 1848.

More than 200 years after the Edo laws, incidents in the USA surrounding a photograph by Andres Serrano called Piss Christ, of a plastic crucifix set in a container of urine, and an exhibition of photographs made in the 1980s by Robert Mapplethorpe, which portrayed sexually explicit homosexual acts, also raised the specter of government involvement in artistic expression for many of the same reasons as in Tokugawa Japan. However, if the impulse to enforce social conformity is a very old one, in the USA, the right of the nation and of the states to maintain a decent society has often found itself in conflict with the US Constitution’s First Amendment, which protects freedom of speech and, by implication, freedom of artistic expression. Such legislation does not exist in totalitarian regimes, in which the relationship between censorship and Propaganda may be most explicit.

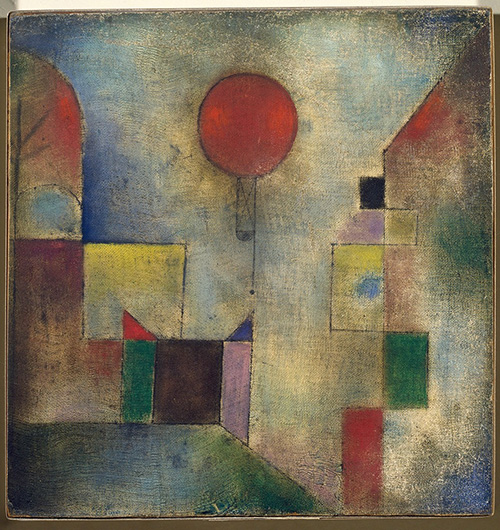

In Nazi Germany, artists were drafted to depict the promised paradise of the Third Reich, while avant-garde and modern works were labeled ‘degenerate.’ No specific definition of ‘degenerate art’ was enunciated, but works condemned included those by Jewish artists, those with pacifist sentiments, all German Expressionist paintings, abstract art, and art made by anyone associated with the Bauhaus. The USSR and China also viewed modernism with hostility. As Carmilly-Weinberger stated, ‘In China, where Western art first became known in the middle of the nineteenth century, the communists under Mao Tse-Tung (Zedong) and especially in the era of the Gang of Four, rejected modern art as “decadent.” ‘ The use of art became totally distorted under the Soviet system of censorship, which was all-pervasive. On April 23rd, 1932, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party issued a decree on the reconstruction of literary and artistic organizations. Government support of the arts became the only support available. The Academy’s definition of ‘true art’ was Socialist Realism. Ironically, while the communists labeled modern art as decadent and bourgeois, in the USA during the McCarthy era in the late 1940s and early 1950s, modern art was feared as a tool of communist infiltration into American democracy. During this period, the American government maintained an official policy of censorship.

Boime proposed that all art is political, whether it directly serves the needs of the State or seems to hover in the realm of fantasy or escapism. He claimed that the martialing of sculpture and its related cultural conditions was not the result of chance but was deliberately designed to complement political policy or social aspirations. For example, the successive visualizations in 19th-century French sculpture may have been rhetorically concealed under critical claims to greatness, beauty, spiritual experience, and creative inspiration, but they were still visualizations of political, social, and civic order. It was perhaps only with Rodin that modern sculpture began to derive from deeply held personal, and not necessarily political, values. Rodin modernized traditional approaches and learned to use sculpture for mass appeal. In fact, the right of the artist to pursue a personal vision—the concept of complete artistic freedom—is a legacy only of the 18th and 19th centuries. From antiquity, with only rare exceptions, the artist served the needs of the Church, State, and patron. He created the image for the realm and always on the terms set by his patron. Even the cult of genius that emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries did not free the artistic spirit nor make the artist a political or cultural rebel.

Erotic art continues to be the subject of censorship. In the USA, sexual expression that is indecent but not obscene is protected by the First Amendment. Laws prohibiting obscenity were understood to stem from governmental responsibility for the ‘dignity of the community’, as well as the ideological merger of the laws of blasphemy and offences against sexual decency. Although by the mid-1990s, the definition of obscenity in the USA excluded works of serious artistic expression, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was a generally dangerous climate for sexually explicit or controversial art, as radical politicians and special-interest groups sought to purge from the public discourse words, symbols, or images perceived as offensive to the community or as a challenge to its social pieties and conventions. These conservatives sought to redefine the boundaries of artistic freedom protected by the First Amendment of the US Constitution and to use government funding programs as a vehicle to suppress or discourage dissenting voices.

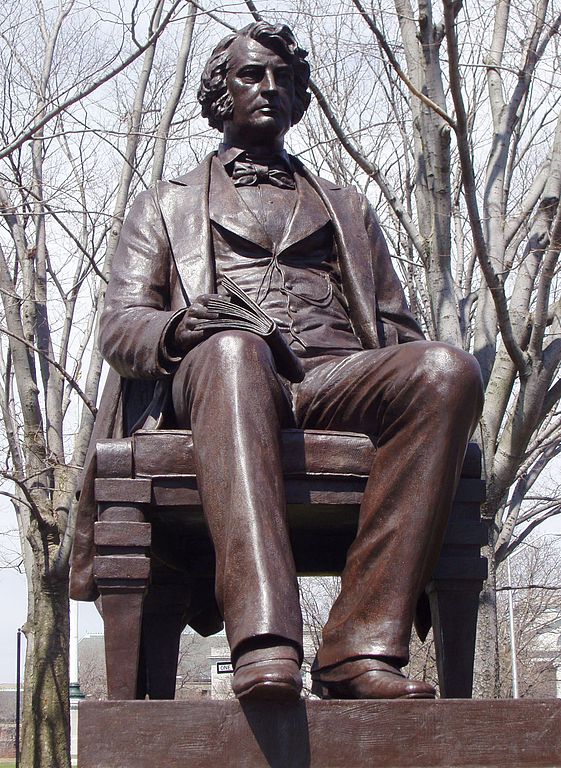

The idea that art is appropriate for some but not others is a characteristic of censorship that goes back, at least to Aristotle. Gender, age, and social class have all been used to determine the susceptibility of a given group of people to social and moral corruption. Such yardsticks reveal the self-perceived moral superiority and arrogance of the censor. Academies and guilds of the West, originally formed to benefit the artist, played a part in restricting artistic freedom. They exercised an inhibiting influence on women artists, either by banning female students completely or by prohibiting certain practices to them. In 1806, for example, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia designated certain days as Ladies’ Days, when the statute regarding nudity was dropped. Such an attitude invariably reinforced patriarchal production and control in the arts. In a different example of patriarchal control, the American sculptor Anne Whitney anonymously won a competition in 1875 to sculpt a memorial portrait of Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, but the commission was rescinded when the committee discovered her gender, the male jurors arguing that a proper portrayal of a man by a woman was impossible. In 1902 Whitney nevertheless cast the statue, which was placed in Harvard Square, Cambridge, MA.

By the late 20th century, corporate sponsorship had, according to some, created an institutionalized censorship of the cultural realm. The American artist Hans Haacke elaborated on this point:

“Given the scarcity of funds from other sources, art institutions have no choice but to invite the seducers of public opinion to exploit their institutions’ aura of “disinterestedness”. A public-relations officer of Mobil once pointed out that his company looks at every application for the sponsorship of an art event in the same way it does when it decides whether to open a gas station on a street corner. It must be profitable. He and his colleagues in other corporations know that only high-visibility, non-controversial art events that pack in the crowds yield what they are looking for. Events with high entertainment value are best suited to the sponsor’s desire to bask in the glow of culture, at peace with the world.”

Ai Weiwei, Remembering and the Politics of Dissent

Dangerous Art

All art is political in the sense that all art takes place in the public arena and engages with an already existing ideology. Yet there are times when art becomes dangerously political for both the artist and the viewers who engage with that art. Think of Jacques-Louis David’s involvement in the French Revolution—his individual investment in art following the bloodshed —and his imprisonment during the reign of terror. If it were not for certain sympathizers, David may well have ended up another victim of the guillotine. Goya is another example of an artist who fell foul of government power. There are instances in the 20th century when artists have faced down political power directly. Consider the photomontages of John Heartfield. Heartfield risked his life at times to produce covers for the magazine A/Z, which defied both Hitler and the Nazi Party.

Ai Weiwei

The Chinese artist Ai Weiwei offers an important contemporary example. In 2011, Weiwei was arrested in China following a crackdown by the government on so-called “political dissidents” (a specific category that the Chinese government uses to classify those who seek to subvert state power) for “alleged economic crimes” against the Chinese state. Weiwei has used his art to address both the corruption of the Chinese communist government and its outright neglect of human rights, particularly in the realm of freedom of speech and thought. Weiwei has been successful in using the internet (which is severely restricted in China) as a medium for his art. His work is informed by two interconnected strands, his involvement with the Chinese avant-garde group “Stars” (which he helped found in 1978 during his time at the Beijing Film Academy) and the fact that he spent some of his formative years in New York, engaging there with the ideas of conceptual art, in particular the idea of the ready-made. Many of the concepts and much of the material that Weiwei uses in his art practice are informed by post-conceptual thinking.

An International Audience

Weiwei has exhibited successfully in the West in many major shows, for example, the 48th Venice Biennale in Italy (1999) and Documenta 12 (2007). He also exhibited Sunflower Seeds (October 2010) in the Turbine Hall in the Tate Modern. In this work, Weiwei filled the floor of the huge hall with one hundred million porcelain seeds, each individually hand-painted in the town of Jingdezhen by 1,600 Chinese artisans. Participants were encouraged to walk over the exhibited space (or even roll in the work) in order to experience the ideas of the effect of mass consumption on Chinese industry and 20th-century China’s history of famine and collective work. However, on October 16, 2010, Tate Modern stopped people from walking on the exhibit due to health liability concerns over porcelain dust.

“…a natural disaster is a public matter.”

Perhaps the work that contributed most to Weiwei’s current imprisonment and the destruction of his studio was his investigation of corruption in the construction of the schools that collapsed during the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan, China. Like many others, Weiwei investigated how improper material and the contravention of civil engineering laws led to the wholesale destruction of schools (which led in turn to the deaths of thousands of children trapped within them), Weiwei has produced a list of all the victims of the earthquake on his blog. This act is typical of Weiwei’s use of the internet to communicate information. This information is his “art,” in much the way that American artists of the late 1960s used words and ideas as art.

So Sorry

In his retrospective show So Sorry (October 2009 to January 2010, Munich, Germany), Weiwei created the installation Remembering on the façade of the Haus der Kunst. It was constructed from nine thousand children’s backpacks. They spelled out the sentence “She lived happily for seven years in this world” in Chinese characters (this was a quote from a mother whose child died in the earthquake). Regarding this work, Weiwei said,

“The idea to use backpacks came from my visit to Sichuan after the earthquake in May 2008. During the earthquake many schools collapsed. Thousands of young students lost their lives, and you could see bags and study material everywhere. Then you realize individual life, media, and the lives of the students are serving very different purposes. The lives of the students disappeared within the state propaganda, and very soon everybody will forget everything.”

The title of the show referred to the apologies frequently expressed by governments and corporations when their negligence leads to tragedies, such as the collapse of schools during the earthquake. Two months before the opening of this exhibition, Weiwei suffered a severe beating from Chinese police in Chengdu in August 2009, where he was trying to testify for Tan Zuoren, a fellow investigator of the shoddy construction and the student casualties. Weiwei underwent emergency brain surgery for internal bleeding as a result of the assault.

The Arrest

On April 3rd, 2011, Weiwei was arrested at Beijing airport while waiting for a flight to Hong Kong. While his detention is broadly believed to be linked to his criticism of the Chinese government, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs declared that he is “under investigation for alleged economic crimes.” Weiwei’s participation in the Jasmine Rallies, a series of peaceful protests that took place all over China in February, no doubt contributed to his arrest.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Kitagawa Utamaro, The Four Accomplishments. Triptych of polychrome woodblock prints; ink and color on paper, ca. 1788-90. A Ukiyo woodcut depicting courtesans learning calligraphy, paint, play the game Go, and learn the lute (Image source: Metropolitan Museum of Art) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 2. Paul Klee, Red Balloon. Oil on chalk primed gauze, mounted on board, 1922. The Nazis raided Klee’s home seized 102 pieces of art, and had him dismissed from his teaching position (Image source: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York via Artstor. Used with permission. For educational use only)

- Figure 3. Anne Whitney’s sculpture of Charles Sumner in Harvard Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts (Image source: Daderot via Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 4. Ai Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds, 2010, hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds; hand-formed and painted by artisans in the historic porcelain-producing city of Jingdezhen in northern Jiangxi, China (Image source: Larry Qualls via Artstor. Used wth permission. For educational use only)

- Figure 5. A close-up view of the Sunflower Seeds, by Ai Weiwei (Image source: Drew Bates via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 6. Visitors outside the Ai Weiwei show, So Sorry, Munich. Backpacks on the facade of the Haus der Kunst (Munich; Image source: Briaxis Fernández Méndez via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Figure 7. Close-up of the backpacks from Ai Weiwei’s “Remembering” on the facade of the Haus der Kunst in Munich (Image source: Douglas LeMoine via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

Candela Citations

- Ai Weiwei, Kui Hua Zi (Sunflower Seeds). Authored by: Megan Lorraine Debin. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/ai-weiwei-kui-hua-zi-sunflower-seeds/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Censorship. Authored by: Barbara Hoffman. Provided by: Grove Art Online. Retrieved from: https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/display/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000015205?rskey=o4tLxa. License: All Rights Reserved

- Freedom of Expression in the Arts and Entertainment. Provided by: ACLU. Retrieved from: https://www.aclu.org/documents/freedom-expression-arts-and-entertainment. License: All Rights Reserved