Chapter 12.2: Mesoamerica

Avocado, tomato, and chocolate. You are likely familiar with at least some of these food items. Did you know that they all originally come from Mexico, and are all based on Nahuatl words (ahuacatl, tomatl, and chocolatl) that were eventually adopted by the English language?

Nahuatl is the language spoken by the Nahua ethnic group that is found today in Mexico, but with deep historical roots. You might know one Nahua group: the Aztecs, more accurately called the Mexica. The Mexica were one of many Mesoamerican cultural groups that flourished in Mexico prior to the arrival of Europeans in the sixteenth century.

Where was Mesoamerica?

Mesoamerica refers to the diverse civilizations that shared similar cultural characteristics in the geographic areas comprising the modern-day countries of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. Some of the shared cultural traits among Mesoamerican peoples included a complex pantheon of deities, architectural features, a ballgame, the 260-day calendar, trade, food (especially a reliance on maize, beans, and squash), dress, and accoutrements (additional items that are worn or used by a person, such as earspools).

Some of the most well-known Mesoamerican cultures are the Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Teotihuacan, Mixtec, and Mexica (or Aztec).

The geography of Mesoamerica is incredibly diverse—it includes humid tropical areas, dry deserts, high mountainous terrain, and low coastal plains. An anthropologist named Paul Kirchhoff first used the term “Mesoamerica” (meso is Greek for “middle” or “intermediate”) in 1943 to designate these geographical areas as having shared cultural traits prior to the invasion of Europeans, and the term has remained.

Typically when we discuss Mesoamerican art we are referring to art made by peoples in Mexico and much of Central America. When people mention Native North American art, they are usually referring to indigenous peoples in the U.S. and Canada, even though these countries are technically all part of North America. More recently, archaeologists and art historians have considered connections between the Southwestern and Southeastern U.S. and Mesoamerica, an area sometimes called either the Greater Southwest or Greater Mesoamerica. Focusing on these connections demonstrates how people were in contact with one another through trade, shared beliefs, migration, or conflict. Ball courts, for instance, are found in Arizona sites such as the Pueblo Grande of the Hohokam.

It is important to remember that modern-day geographic terms—like Mesoamerica or the Southwestern U.S.—are recent designations.

This essay generalizes about Mesoamerican cultures, but keep in mind that each possessed unique qualities and cultural differences. Mesoamerica was not homogenous.

What Language Did People Speak?

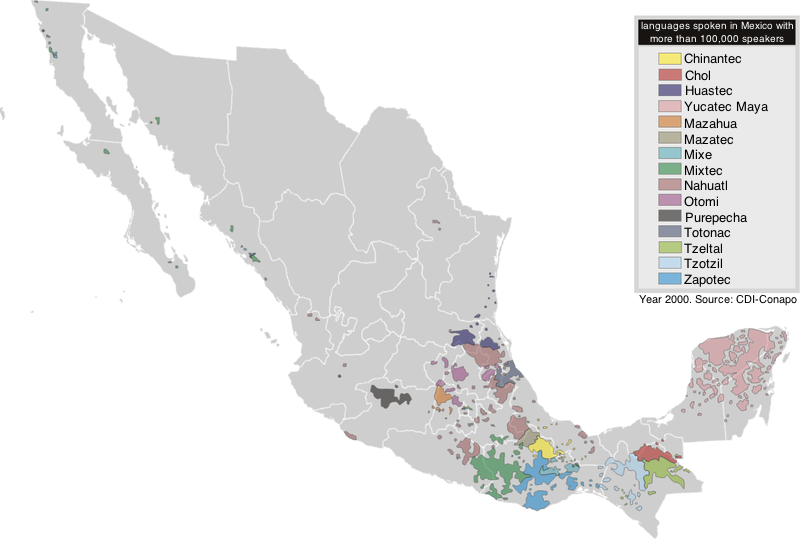

There was no single language that united the peoples of Mesoamerica. Linguists believe that Mesoamericans spoke more than 125 different languages. For instance, Maya peoples did not speak “Mayan”, but could have spoken Yucatec Maya, K’iche, or Tzotzil among many others. The Mexica belonged to the bigger Nahua ethnic group, and therefore spoke Nahuatl.

To students learning about Mesoamerica for the first time, the incredible diversity of people, languages, and even deities can be overwhelming. I recall my first Mesoamerican art history class vividly. I was intimidated by my lack of familiarity with different Mesoamerican words, languages, and cultural groups. By the end of the semester, I was proud that I could differentiate between the Zapotec and Mixtec and could spell Tlaloc. It took me a few more years to be able to spell and pronounce words like Tlacaxipehualiztli (Tla-cawsh-ee-pay-wal-eeezt-li) or Huitzilopochtli (Wheat-zil-oh-poach-lee).

What do “Pre-Columbian” and “Mesoamerica” mean?

by Dr. Maya Jimenez

The original inhabitants of the Americas traveled across what is now known as the Bering Strait, a passage that connected the westernmost point of North America with the easternmost point of Asia. The Western hemisphere was disconnected from Asia at the end of the last Ice Age, around 10,000 B.C.E.

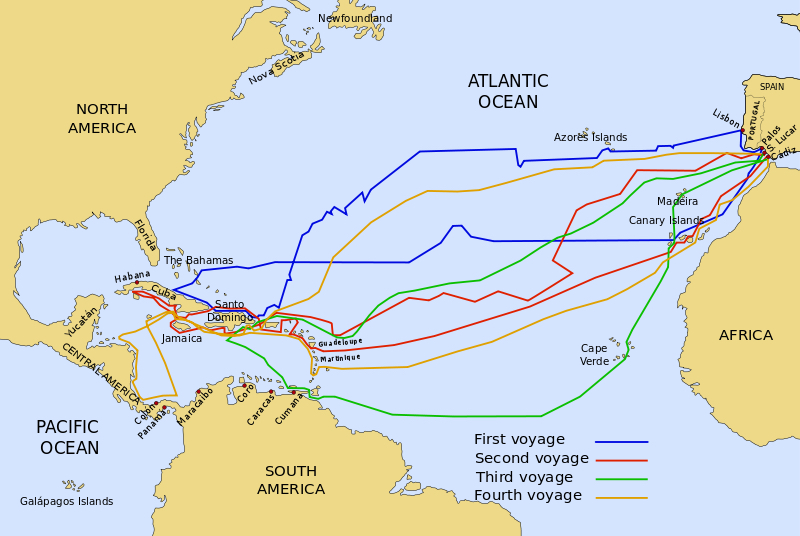

In 1492, the Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus arrived at the islands of Cuba and Hispaniola (today Haiti and the Dominican Republic), mistakenly thinking he had reached Asia. Columbus’ miscalculation marked the first step in the colonization of the Americas, or what was then seen as a “New World.” Incorrectly referring to the native inhabitants of Hispaniola as “Indians” (under the assumption that he had landed in India), Columbus established the first Spanish colony of the Americas. “Pre-Columbian” thus refers to the period in the Americas before the arrival of Columbus.

Teōtīhuacān reached its peak from the 1st to the mid-6th century C.E. The main structures include the Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon, Avenue of the Dead, and the Temple of Quetzalcoatl (feathered serpent). Teotihuacan was home to as many as 125,000 people. The name Teōtīhuacān was given by the Aztecs long after the city had been abandoned in c. 550 C.E. The original name is lost.

The Spanish conquistadores (conquerors) found that the “New World” was in fact not new at all, and that the indigenous people of Mesoamerica had established advanced civilizations with densely populated cities and towering architectural monuments such as at Teōtīhuacān, as well as advanced writing systems.

The term pre-Columbian is complicated however. For one thing, although it refers to the indigenous peoples of the Americas, the phrase does not directly reference any of the many sophisticated cultures that flourished in the Americas (think of the Aztec, Inca, or Maya, to name only a few) and instead invokes a European explorer. For this reason and because indigenous peoples flourished before and after the arrival of the Europeans, the term is often seen as flawed. Other terms such as pre-Hispanic, pre-Cortesian, or more simply, ancient Americas, are sometimes used.

What does “Mesoamerica” mean?

The region of Mesoamerica—which today includes central and south Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador—consists of a diverse geographic landscape of highlands, jungles, valleys, and coastlines. Mesoamericans did not exploit technological innovations such as the wheel—though they were used in toys— and did not develop metal tools or metalworking techniques until at least until 900 C.E. Instead, Mesoamerican artists are known for producing megalithic (large stone) sculpture and extremely sharp weapons from obsidian (volcanic glass). Featherwork and stonework in basalt, turquoise, and jade dominated Mesoamerican artistic production, while exceptional textiles and metallurgy flourished further south, among pre-Columbian Andean and Central American cultures, respectively.

Video

Unearthing the Aztec past, the destruction of the Templo Mayor (6:45)

Mesoamerican Culture

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures shared certain characteristics such as the ritual ballgame, pyramid building, human sacrifice, maize as an agricultural staple, and deities dedicated to natural forces (i.e. rain, storm, fire). Additionally, some Mesoamerican societies developed sophisticated systems of writing, as well as an advanced understanding of astronomy (which allowed for the development of accurate and complex calendar systems, including the 260-day sacred calendar and the 365-day agricultural calendar). As a result, cities like La Venta and Chichen Itza were aligned in relation to cardinal directions and had a sacred center. The fact that many of these cultural trademarks persisted for more than 2,000 years across civilizations as distinct as the Olmec (c. 1200–400 B.C.E.) and the Aztec (c. 1345 to 1521 C.E.), demonstrates the strong cultural bond of Mesoamerican cultures.

The 260-day Ritual Calendar vs. the 365-day Calendar

Other shared features among Mesoamerican peoples were the 260-day and 365-day calendars. The 260-day calendar was a ritual calendar, with 20 months of 13 days. Based on the sun, the 365-day calendar had 18 months of 20 days, with five “extra” nameless days at the end. It was the count of time used for agriculture.

Imagine both of these calendars as interlocking wheels. Every 52 years they completed a full cycle, and during this time special rituals commemorated the cycle. For example, the Mexica celebrated the New Fire Ceremony as a period of renewal. These cycles were understood as life cycles, and so reflect creation, death, and rebirth. The Maya (especially during the Classic period), also used a Long Count calendar in addition to the two already mentioned (rather than a cyclical calendar, the Long Count marked time as if along an extended line that does not repeat).

Religion and Pantheon of Gods

A complex pantheon of gods existed within each Mesoamerican culture. Many groups shared similar deities, although there was a great deal of variation. Deities that had important roles across Mesoamerica included a storm/rain god and a feathered serpent deity. Among the Mexica, this storm/rain god was known as Tlaloc, and the feathered serpent deity was known as Quetzalcoatl. The Maya referred to their storm/rain deity as Chaac (there are multiple spellings). The equivalent of Quetzalcoatl among different Maya groups included Kukulkan (Yucatec Maya) and Q’uq’umatz (K’iche Maya). Cocijo is the Zapotec equivalent of the storm/rain god. Many artworks exist that show these two deities with similar features. The storm/rain deity often has goggle eyes and an upturned mouth/snout. Feathered serpent deities typically showed serpent features paired with feathers.

Religion and Pantheon of Gods

A complex pantheon of gods existed within each Mesoamerican culture. Many groups shared similar deities, although there was a great deal of variation. Deities that had important roles across Mesoamerica included a storm/rain god and a feathered serpent deity. Among the Mexica, this storm/rain god was known as Tlaloc, and the feathered serpent deity was known as Quetzalcoatl. The Maya referred to their storm/rain deity as Chaac (there are multiple spellings). The equivalent of Quetzalcoatl among different Maya groups included Kukulkan (Yucatec Maya) and Q’uq’umatz (K’iche Maya). Cocijo is the Zapotec equivalent of the storm/rain god. Many artworks exist that show these two deities with similar features. The storm/rain deity often has goggle eyes and an upturned mouth/snout. Feathered serpent deities typically showed serpent features paired with feathers.

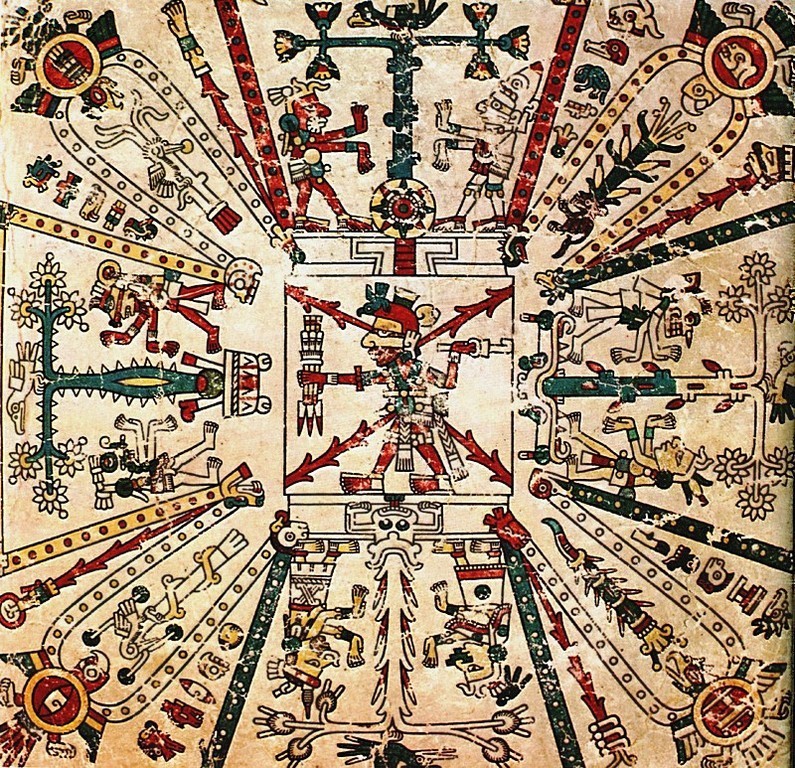

It is difficult to generalize about Mesoamerican religious beliefs and cosmological ideas because they were so complex. Throughout Mesoamerica, there was a general belief in the universe’s division along two axes: one vertical, the other horizontal. At the center, where these two axes meet, is the axis mundi, or the center (or navel) of the universe. On the horizontal plane, four directions branch off from the axis mundi. Think of the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, and west). On the vertical plane, we generally find the world split into three major realms: the celestial, terrestrial, and underworld.

One Mexica example helps to clarify this complex cosmological system. An image in the Codex Féjervary-Mayer displays the cosmos’s horizontal axis. In the center is the deity Xiuhtecuhtli (a fire god), standing in the place of the axis mundi. Four nodes (what look almost like trapezoidal petals) branch off from his position, creating a shape called a Maltese Cross. East (top) is associated with red, south (right) with green, west (bottom) with blue, and north (left) with yellow. A specific plant and bird accompany each world direction: blue tree and quetzal (a colorful bird native to Mexico and the southern U.S., east), cacao and parrot (south), maize and blue-painted bird (west), and cactus and eagle (north). Two figures flank the plant in each arm of the cross. Together, these figures and Xiuhtecuhtli represent the Nine Lords of the Night. This cosmogram describes how the Mexica conceived of the universe.

Video

The Sun Stone (The Calendar Stone) (6:28)

Chavín de Huántar

Chavín de Huántar is an archaeological and cultural site in the Andean highlands of Peru. Once thought to be the birthplace of an ancient “mother culture,” the modern understanding is more nuanced. The cultural expressions found at Chavín most likely did not originate in that place, but can be seen as coming into their full force there. The visual legacy of Chavín would persist long after the site’s decline in approximately 200 B.C.E., with motifs and stylistic elements traveling to the southern highlands and to the coast. The location of Chavín seems to have helped make it a special place—the temple built there became an important pilgrimage site that drew people and their offerings from far and wide. At 10,330 feet (3150 meters) in elevation, it sits between the eastern (Cordillera Negra—snowless) and western (Cordillera Blanca—snowy) ranges of the Andes, near two of the few mountain passes that allow passage between the desert coast to the west and the Amazon jungle to the east. It is also located near the confluence of the Huachesca and Mosna Rivers, a natural phenomenon of two joining into one that may have been seen as a spiritually powerful phenomenon.

Over the course of 700 years, the site drew many worshipers to its temple who helped spread the artistic style of Chavín throughout highland and coastal Peru by transporting ceramics, textiles, and other portable objects back to their homes.

The temple complex that stands today is comprised of two building phases: the U-shaped Old Temple, built around 900 B.C.E., and the New Temple (built approximately 500 B.C.E.), which expanded the Old Temple and added a rectangular sunken court. The majority of the structures used roughly-shaped stones in many sizes to compose walls and floors. Finer smoothed stone was used for carved elements. From its first construction, the interior of the temple was riddled with a multitude of tunnels, called galleries. While some of the maze-like galleries are connected with each other, some are separate.

The galleries all existed in darkness—there are no windows in them, although there are many smaller tunnels that allow for air to pass throughout the structure. Archaeologists are still studying the meaning and use of these galleries and vents, but exciting new explorations are examining the acoustics of these structures, and how they may have projected sounds from inside the temple to pilgrims in the plazas outside. It is possible that the whole building spoke with the voice of its god.

The god for whom the temple was constructed was represented in the Lanzón (left), a notched wedge-shaped stone over 15 feet tall, carved with the image of a supernatural being, and located deep within the Old Temple, intersecting several galleries. Lanzón means “great spear” in Spanish, in reference to the stone’s shape, but a better comparison would be the shape of the digging stick used in traditional highland agriculture. That shape would seem to indicate that the deity’s power was ensuring successful planting and harvest.

The Lanzón depicts a standing figure with large round eyes looking upward. Its mouth is also large, with bared teeth and protruding fangs. The figure’s left hand rests pointing down, while the right is raised upward, encompassing the heavens and the earth. Both hands have long, talon-like fingernails. A carved channel runs from the top of the Lanzón to the figure’s forehead, perhaps to receive liquid offerings poured from one of the intersecting galleries.

Drawing of the Lanzon at Chavín de Huántar (Richard Burger and Luis Caballero)

Two key elements characterize the Lanzón deity: it is a mixture of human and animal features, and the representation favors a complex and visually confusing style. The fangs and talons most likely indicate associations with the jaguar and the caiman—apex predators from the jungle lowlands that are seen elsewhere in Chavín art and in Andean iconography. The eyebrows and hair of the figure have been rendered as snakes, making them read as both bodily features and animals.

Further visual complexities emerge in the animal heads that decorate the bottom of the figure’s tunic, where two heads share a single fanged mouth. This technique, where two images share parts or outlines, is called contour rivalry, and in Chavín art it creates a visually complex style that is deliberately confusing, creating a barrier between believers who can see its true form and those outside the cult who cannot. While the Lanzón itself was hidden deep in the temple and probably only seen by priests, the same iconography and contour rivalry was used in Chavín art on the outside of the temple and in portable wares that have been found throughout Peru

The serpent motif seen in the Lanzón is also visible in a nose ornament in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art (above). This kind of nose ornament, which pinches or passes through the septum, is a common form in the Andes. The two serpent heads flank right and left, with the same upward-looking eyes as the Lanzón. The swirling forms beneath them also evoke the sculpture’s eye shape. An ornament like this would have been worn by an elite person to show not only their wealth and power but their allegiance to the Chavín religion. Metallurgy in the Americas first developed in South America before traveling north, and objects such as this that combine wealth and religion are among the earliest known examples. This particular piece was formed by hammering and cutting the gold, but Andean artists would develop other forming techniques over time.

Video

Chavin (Archaeological Site) (UNESCO/NHK) (2:56)

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. A map of Mesoamerica showing the modern day countries (Image source: Smarthistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 2. Indigenous languages in Mexico currently spoken by more than 100,000 people (Image source: Smarthistory)

- Figure 3. The routes of the four Voyages of Christopher Columbus, 1492-1504 to the Caribbean Islands and the coast of Central America (Image source: Khan Academy) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 4. Teotihuacan (Pyramid of the Sun) with a view of the Street of the Dead, Mexico. 1-750 AD (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest. Werner Forman Archive / Universal Images Group. Rights Managed)

- Figure 5. Cylindrical vessel with ball game scene, c. 682-701 C.E., Late Classic, Maya, ceramic, 20.48 cm high (Image source: Dallas Museum of Art. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 6. The Mesoamerican god of Quetzalcoatl is depicted as a coiled, feathered serpent. Stone sculpture, Aztec, from Mexico City, c1450 (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, The Granger Collection / Universal Images Group. Rights Managed / For Education Use Only)

- Figure 7. Codex Féjervary-Mayer, 15th century (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 8. From Old Temple at Chavín de Huantar. Oldest representation of the principal divinity of the culture, a half-man, half-feline creature. Carved into a large monolith called El Lanzon and planted in the middle of the Old Temple (Image source: University of California, San Diego via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 9. Nose Ornament, c. 500-200 B.C.E., Peru, North Highlands, Chavín de Huántar, hammered and cut gold, 2.3 cm high (Image source: Cleveland Museum of Art. Used with permission, for education use only)

Candela Citations

- Mesoamerica, an introduction. Authored by: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/mesoamerica-an-introduction/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- What do u201cPre-Columbianu201d and u201cMesoamericau201d mean?. Authored by: Dr. Maya Jimenez. Provided by: Khan Academy. Retrieved from: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/beginners-guide-art-of-the-americas/mesoamerica-beginner/a/pre-columbian-mesoamerica. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike