Chapter 12.10: Japan

Jōmon Culture (Approximately 14,500 B.C.E. – ca. 300 B.C.E.)

Jōmon is the earliest major culture of prehistoric Japan, characterized by pottery decorated with cord-pattern (jōmon) impressions or reliefs. For some time, there has been uncertainty about assigning dates to the Jōmon period, particularly to its onset. The earliest date given is about 14,500 B.C.E., lasting until approximately 300 B.C.E.

Jōmon Pottery

The Jomon Period (c. 14,500 – c. 300 BCE) of ancient Japan produced a distinctive pottery that distinguishes it from the earlier Paleolithic Age. Jomon pottery vessels are the oldest in the world and their impressed decoration, which resembles rope, is the origin of the word jomon, meaning ‘cord pattern’.

Jomon pottery, in the form of simple vessels, was first produced c. 13,000 BCE around Shinonouchi in Nagano, making them the oldest such examples in the world. Another early production site was Odai-Yamamoto in Aomori. Jomon pottery figurines are rather later, the oldest known example being the ‘Jomon Venus’ which dates to c. 5000 BCE.

Jomon pottery was, consequently, gradually replaced by the finer pottery of the Yayoi Period (c. 300 BCE – c. 250 CE), which has no decoration and a reddish color. These wares would be replaced in turn by the higher quality Sue stoneware which was introduced from Korea in the Kofun Period (c. 250 CE – 538 CE).

Dogū (Japanese figurine)

Dogū are abstract clay figurines, generally of pregnant females, made in Japan during the Jōmon period (c. 10,500 to c. 300 BCE). Dogū are reminiscent of the rigidly frontal fertility figures produced by other prehistoric cultures.

Their precise function is unknown, but archaeological evidence suggests they were aids in childbirth as well as fertility symbols. They are also found in simulated burials, indicating some kind of ceremonial function. Fired at a low temperature, they often have crumbly surfaces; many are painted in red.

Tumulus Period (c. 250–552 C.E.).

Haniwa (Japanese sculpture)

Haniwa, unglazed terracotta cylinders and hollow sculptures arranged on and around the mounded tombs (kofun) of the Japanese elite dating from the Tumulus period (c. 250–552 CE). The first and most common haniwa were barrel-shaped cylinders used to mark the borders of a burial ground. Later, in the early 4th century, the cylinders were surmounted by sculptural forms such as figures of warriors, female attendants, dancers, birds, animals, boats, military equipment, and even houses. It is believed that the figures symbolized continued service to the deceased in the other world.

Haniwa vary from 1 to 5 feet (30 to 150 cm) in height, the average being approximately 3 feet (90 cm) high. The human figures were often decorated with incised geometric patterns and pigments of white, red, and blue.

The word “haniwa” is a combination of two Japanese words: “hani” (meaning “circle”) and “wa” (meaning “ring” or “circle”). When first created, haniwa were made in various cylindrical shapes.

The more intricate haniwa were human figures. However, they also included animals like birds, dogs, deer, monkeys, rabbits, and sheep.

Edo Period (1603 – 1868)

Asuka Period 552-646 CE

Buddhism was introduced into Japan in either 538 CE or 552 CE (traditional date) from the Korean kingdom of Baekje (Paekche). Buddhism received official government support in 587 CE during the reign of Emperor Yomei (585-587 CE).

Co-existence with Shinto

The indigenous beliefs of the ancient Japanese included animism and Shinto and neither were particularly challenged by the arrival of Buddhism. Shinto, especially, with its emphasis on the here and now and this life, left a significant gap regarding what happens after death and here Buddhism was able to complete the religious picture for most people. As a consequence, both religions co-existed, many people practised both, and even temples of both faiths existed together on the same site. Many Buddhist deities and figures from Indian mythology were readily incorporated into the already vast Shinto pantheon. At the same time Shinto gods acquired Buddhist names (Ryobu Shinto) so that, for example, the sun goddess Amaterasu was considered an avatar of Dainichi; and Hachiman, the god of war and culture, was the avatar of the Amida Buddha.

Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world,” refers to a genre of Japanese woodblock prints. These inexpensive prints were produced in variety of styles, some using only black ink, while others used layers of color. Considered a low form of art created for merchants and workers, ukiyo-e originated in 1670, but soon became a form of art that was known both for its appeal to the average person and its artistic quality.

The work of the great masters of ukiyo-e, Kitagawa Utamaro, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Katsushika Hokusai, greatly impacted European artists. Some artists, like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, were particularly drawn to Japanese prints depicting urban nightlife and its famous or notorious denizens. Utamaro, known primarily for his prints of beautiful Japanese women, influenced artists like Whistler. Others, like Edgar Degas, were more interested in composition strategies and the portrayal of figures in unconventional poses. Hiroshige’s work, which focused on landscape and scenes of ordinary life (unlike the more common depictions of celebrities and scenes of what were called Tokyo’s “pleasure district”) influenced Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists like Vincent van Gogh. Indeed, van Gogh made multiple copies of images from Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856-58).

Japonism

Japonism, also often referred to by the French term, japonisme, refers to the incorporation of either iconography or concepts of Japanese art into European art and design. As artists sought new ways of depicting their world and a break from the Western Renaissance tradition, the Japanese aesthetic was a major impetus in the development of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Aestheticism, Art Nouveau, and Tonalism. Virtually all of the Impressionists were influenced by ukiyo-e prints, inspired by the everyday subject matter, limited palette and flat planes of color, asymmetrical composition, and unexpected points of view. Claude Monet’s extensive collection of prints can be seen today at his house/museum in Giverny, France; Vincent van Gogh and Auguste Rodin also amassed large collections of prints.

The Formats of Two-Dimensional Works

Japanese two-dimensional works of art can take a number of different formats—printed books (ehon), single- or multi-sheet prints (hanga), paintings in the form of hanging-scrolls (kakemono) and handscrolls (emaki), moveable folding screens (byōbu), usually in pairs, sliding door paintings (fusuma-e) and smaller scale fan paintings and album leaves. The screens and sliding doors also served to exclude draughts or divide rooms, and were changed according to the season. Hanging-scrolls were displayed, sometimes in pairs or sets of three in the tokonoma (ceremonial alcoves) of reception rooms of mansions and, again, could be changed according to the season, or to honor a special visitor. All such works were viewed seated at floor level on tatami mats.

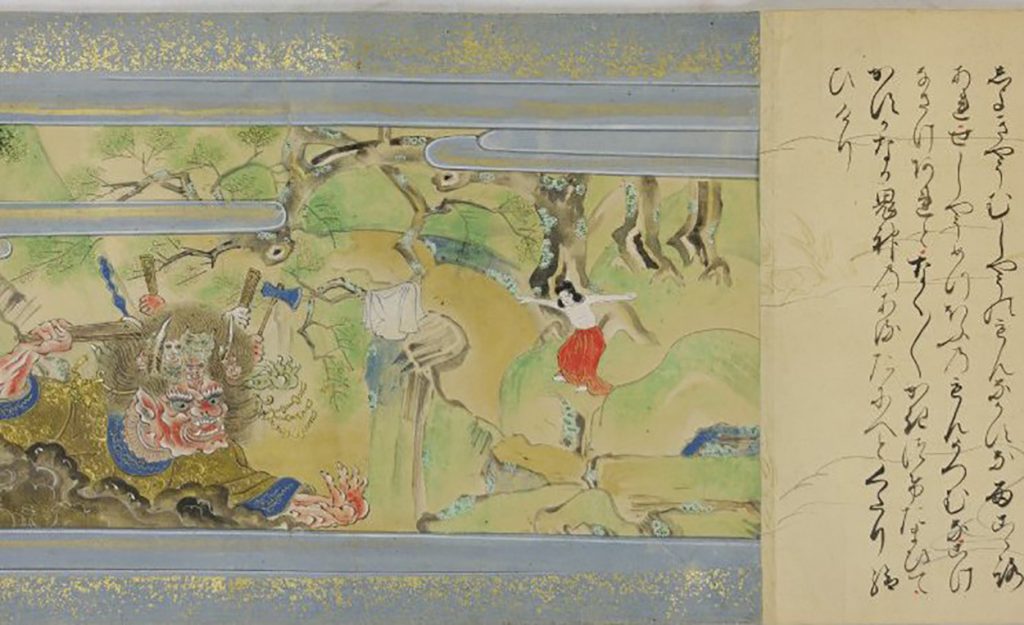

Handscrolls (like the one above) were usually placed on a low table and unrolled from right to left to show a narrative story or seasonal sequence. Print series, small-scale paintings or fan paintings were often mounted in albums. Individual prints, especially the Ukiyo-e portraits of popular actors or courtesans, might be pasted to a screen. The size of the print was limited by the size of cherry-wood block available. Often two, three or more sheets were arranged side by side to depict a wider scene. Books were printed two pages to one sheet of paper, which was then folded, and the sheets sewn together at the spine with a plain cover.

Hanging Scrolls

Kakemono (hanging scrolls) were originally used to display Buddhist paintings, and calligraphy. The painting in ink and colors on either silk or paper was backed with paper and given silk borders chosen to harmonize with the painting. Finally, a roller was affixed to the bottom. Scrolls were kept in specially made paulownia wooden boxes to protect them from dust, changing climate conditions and insect damage.

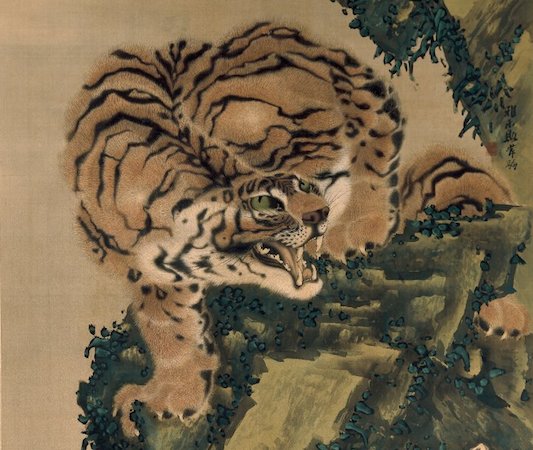

Tiger Paintings

Tiger paintings were very popular in Japan, but as the artists would never have seen a real tiger, they must have worked from skins. Gan Ku became famous for his paintings of tigers and has brought this one immediately to life with his strong imagination and skillful brushwork. The fearsome advance of the beast towards the viewer is suggested by the powerfully hunched shoulders, the placing of its feet and the tip of the tail, just visible, which all emphasize the animal’s size and strength. Gan Ku has used the careful brushwork of Chinese academic painters to depict the tiger, while the setting of tree, rocks and water is in a much freer, dynamic style typical of his later ink and wash works. In 1784 Gan Ku entered the service of Prince Arisugawa and for this painting he uses the art-name Utanosuke which was given to him by the prince. He seems to have used this name until about 1796.

The signature reads ‘Utanosuke Gan Ku’, and the seals read “Kakan” and “Gan Ku.”

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Reconstructed Jōmon settlement at the Forest of Uenohara Jōmon Site, Kagoshima prefecture, Japan (Image source: Britannica. For education use only)

- Figure 2. Reconstructed Jōmon settlement at the Forest of Uenohara Jōmon Site, Kagoshima prefecture, Japan (Image source: Britannica. For education use only)

- Figure 3. A dogū figurine (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 4. A Haniwa garden in Heiwadai Park, Miyazaki, Japan (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 5. Haniwa horse statuette (Kofun period of Japan). From the Paris, Guimet Museum. Haniwa (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 6. The Great Buddha (Daibutsu), 17th century replacement of an 8th-century sculpture, Tōdai-ji, Nara, Japan (Image source: photo by Deanna MacDonald via Khan Academy) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7. Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa (c. 1831) is an iconic work that became known worldwide and remains very popular (Image source: From the Metropolitan Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 8. Shaka no honji (The Story of Sakyamuni)

- Figure 9. Tiger (detail), Gan Ku, Tiger, hanging scroll, Edo period, c. 1784-96, ink and color on silk. 169 x 114.5 cm, Japan (Image source: © The Trustees of the British Museum. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 10. Tiger painting, Gan Ku, Tiger, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk. 169 x 114.5 cm, Japan, Edo period, c. 1784-96 (Image source: The Trustees of the British Museum. Used with permission, for education use only)

Candela Citations

- Buddhism in Ancient Japan. Authored by: Mark Cartwright. Provided by: World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1080/buddhism-in-ancient-japan/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Jomon Pottery. Authored by: Mark Cartwright. Provided by: World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from: https://www.worldhistory.org/Jomon_Pottery/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Ju014dmon culture. Authored by: The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Provided by: Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Jomon-culture. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- haniwa. Authored by: The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Provided by: Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/art/haniwa. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Japanese art: the formats of two-dimensional works. Authored by: The British Museum. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/japanese-art-the-formats-of-two-dimensional-works/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Funerary Art pt 1: Haniwa. Provided by: Seattle Artist League. Retrieved from: https://www.seattleartistleague.com/2023/07/15/haniwa/. License: All Rights Reserved