Chapter 12.1: Native North America

Geography

Typically, when people discuss Native American art, they are referring to peoples in what is today the United States and Canada. You might sometimes see this referred to as Native North American art, even though Mexico, the Caribbean, and those countries in Central America are typically not included. These areas are commonly included in the arts of Mesoamerica (or Middle America), even though these countries are technically part of North America.

So, how do we consider so many groups of such diverse natures? We tend to treat them geographically: Eastern Woodlands (sometimes divided between North and Southeast), Southwest and West (or California), Plains and Great Basin, and Northwest Coast and North (Sub-Arctic and Arctic). While this is by no means a perfect way of addressing the varied tribes and First Nations within these areas, such a map can help to reveal patterns and similarities.

Chronology

Chronology (the arrangement of events into specific time periods in order of occurrence) is tricky when discussing Native American or First Nations art. Each geographic region is assigned different names to mark time, which can be confusing to anyone learning about the images, objects, and architecture of these areas for the first time. For instance, for the ancient Eastern Woodlands, you might read about the Late Archaic (c. 3000–1000 B.C.E.), Woodland (c. 1100 BCE–1000 C.E.), Mississippian (c. 900–c. 1500/1600 C.E.), and Fort Ancient (c. 1000–1700) periods. But if we turn to the Southwest, there are alternative terms like Basketmaker (c. 100 B.C.E.–700 C.E.) and Pueblo (700–1400 C.E.). You might also see terms like pre- and post-Contact (before and after contact with Europeans and Euro-Americans) and Reservation Era (late nineteenth century) that are used to separate different moments in time. Some of these terms speak to the colonial legacy of Native peoples because they separate time-based on interactions with foreigners. Other terms like Prehistory have fallen out of favor and are problematic since they suggest that Native peoples didn’t have a history prior to European contact.

Diverse regions

The vast geographic and environmental diversity of the North American continent has allowed one of the most culturally diverse regions on the planet to emerge. Societies across the continent have developed beautiful and complex material worlds that reflect the character and personality of their territories. Native North American peoples have responded to the universal problems of life in individual and ingenious ways, making the best use of their natural resources to build strong and expressive communities. Below, objects from the British Museum’s collection, as well as others, illustrate the ways in which separate Native American cultures have lived through a colonial period of immense social and environmental upheaval over the last three hundred years.

The earliest objects in the collection are stone tools made about 8000 years ago by big-game hunters who were part of the Palestinian Tradition. These ancient people were followed by Archaic hunters from 8000-1000 B.C.E. who exploited the new animal and plant resources of a warming climate following the end of the ice age, using specialized tools.

After the Archaic period came the Woodland peoples, from about 800 B.C.E., who lived in settled communities, hunting, fishing, and gathering and cultivating plants. Large earthworks, such as those of the Ohio Hopewell culture (from about 100 B.C.E. to C.E. 600), were created for religious, economic,c and defensive purposes.

Videos

Mesa Verde and the Preservation of Ancestral Pueblo an Heritage (6:19)

Pompey (Hopi-Tea), polychrome jar (6:34)

European Colonization

At the time of European contact in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there would have probably been between two and ten million Native inhabitants. They were incredibly diverse, living as distinct nations with distinct traditions and speaking different languages. European colonization and the expansion of the United States brought diseases and warfare that killed most of the native population. Bison, on which many depended for food, clothing, housing, and tools, were hunted almost to extinction by commercial hunters. Further hardship came as many were forced to live in reservations. Continuing conflict culminated in the Battle of Wounded Knee in 1890 when United States troops massacred hundreds of Dakota after they had surrendered. Today, between two and three million people of native descent live in Canada and the United States of America. They are grouped into more than 1000 bands, tribes or nations all possessing their own oral literatures and histories; their survival and continued vibrancy a testament to the enduring strength of their traditions

The Eastern Woodlands

The peoples of the expansive woodlands of Eastern America live in a large number of tribes, with related religious and linguistic traditions. The people subsisted through hunting, fishing and limited agriculture, trading with and periodically making war on their neighbors.

They were the first Native North American societies to experience the arrival of Europeans, and despite regular outbreaks of disease and warfare, a significant cultural exchange took place as Europeans learned to live and travel in their New World. Native Americans quickly accessed new technologies and markets, fueling an explosion in trade that had a profound effect on all involved.

The Northwest Coast

The societies of the Northwest coast of North America developed in relative isolation between the Coastal Mountains and the Pacific Ocean.

Living in small communities on islands and in fjords, they utilized the huge cedar forests to construct the elaborate heraldic structures now known collectively as totem poles.

The enthusiasm for carving stretched far beyond the poles to encompass all areas of life on the coast, and their ornate canoes could travel across hundreds of miles of ocean in search of fish, whales, trade, or war. Control of the sea allowed chieftains to amass considerable wealth, which they distributed to followers at elaborate feasts known as potlatches.

Masking, a performance art practiced widely on the coast, was an integral part of potlatches, where ancestral tales were performed in long-houses before the tribe and their guests. Some, such as the cedar mask illustrated at the top of the page, were designed to transform mid-dance from one form to another, an essential part of Northwest Coast storytelling.

The Arctic

The shores of the North American continent around and to the north of the Arctic circle are inhabited by people speaking related, though distinct, Eskimo-Aleut languages: these are Aleut, Alutiiq, Yup’ik and Inupiaq in Alaska; Siberian Yup’ik, spoken by the Yuit in Alaska and Siberia; Inuktitut spoken by the Canadian Inuit; and Greenlandic spoken by the Greenland Inuit.

In the past, these peoples have been collectively known as Eskimos. This word, meaning “snowshoe netters,” is often mistakenly translated as “raw meat eaters.” It is today largely rejected, especially by Canadian groups, who prefer using the term “Inuit,” which means “people” in their language.

A world of scarcity

Traditionally, all these people were dependent on the hunting of whales, walrus, seals and caribou, as well as fishing. They shared certain cultural elements, such as the kayak and umiaq (both types of boat), dog sleds, toggling harpoon heads, the ulu (woman’s knife), seal oil lamps, and double-layer skin clothing, as well as certain hunting and fishing techniques, and some religious beliefs and practices.

The sled is mostly made from whale, walrus (penis and rib) and other bone, and wood, tied with seal skin. The shoes on the runners are made of strips of narwhal ivory. It was collected by John Ross(1777- 1856) on the first occasion that this isolated group of Inuit came into contact with Europeans. Although they had virtually no wood, the Inuit did have access to an amalgam of iron and nickel. This came from meteorites, which they named Woman, Tent, and Dog; the type specimens (the first pieces collected by, or known to, scientists) are a knife and lance head also collected in 1818, now in the Natural History Museum, London.

However, there were considerable differences as well. Not all of them lived in snow houses, even seasonally, for example. This common stereotype was mainly informed by the accounts of explorers, who, in their search for a Northwest Passage, came into contact with Canadian Inuit.

The people of the farthest northern reaches of the Americas live in a world of scarcity: finite resources and a hostile environment have created a resourceful and resilient people who retain much of their ancestral tradition and lifestyle. They depend heavily on the animals that live around them, making clothing, complex tools, and even structures from the creatures they hunt and fish. With hunting so vital to Arctic livelihood, a variety of specially adapted tools and techniques were developed specifically to catch and utilize prey both on land and by sea.

Today, there are about 130,000 Native people living in the North American Arctic. In Canada (Nunavut) and Greenland, they have attained some degree of self-government. In Alaska, much economic and political power is held by Native corporations.

The Plains

The people of the North American Plains were predominantly nomadic, living in large territories roamed by great herds of buffalo.

Early adopters of the horse lived in societies governed by profound military and religious traditions that produced richly decorated clothing and weaponry. The Plains peoples fought ferociously to maintain their independence as the European nations of North America spread westwards in the nineteenth century. Eventually, after decades of resistance, most Plains people were forced to live on reservations, where despite documented official efforts to eliminate them, traditional practices and languages have survived.

The Southwest

The peoples of the Southwestern United States have a long tradition of settled life that is reliant on agriculture. Diverse peoples with varied cultural and linguistic traditions, the people of the Southwest have long produced highly decorated pottery, jewelry, and textiles. These objects form part of a cultural and technological exchange with Mexican societies to the south, which remains central to a thriving contemporary art market.

One early regional center to emerge in the Southwest included the extensive site of villages and irrigation canals known as Hohokam (AD 200–1400), a culture regarded as ancestral by the Akimel O´odham and Tohono O´odham of Arizona.

The Mogollon

Another early regional center was Mogollon. Shell ornaments, copper bells, rubber balls, and macaws are only some of the remarkable finds from the archaeological site of Paquimé (also known as Casas Grandes) in northern Mexico. Some of these things traveled on long-distance trade networks that ran from southern Mesoamerica to what is now the southwestern United States, and west to the Gulf of California. Paquimé was a large city filled with several thousand people that flourished for two centuries, from c. 1150 until about 1350 C.E. It is one of many sites associated with the Mogollon tradition (c. 200–1450 C.E.).

Who and where were the Mogollon?

The Mogollon cultural area spanned across what is today northern Mexico into Arizona and New Mexico. Archaeologists named the Mogollon cultural group after a mountain range in southern New Mexico centuries later.

In addition to the Mogollon, the Greater Southwest region included the Hohokam, Ancestral Puebloan, Patayan, and Sinagua cultures. While today scholars tend to discuss them as distinct, it is likely that they are different regional variations and were more entangled than these modern-day divisions suggest.

For reasons still debated, the Mogollon disappear from the archaeological record in the mid-15th century, likely the result of them joining with Pueblo or Hopi villages. Today, multiple Native groups claim descent from the Mogollon or are intertwined with their history, including Zuni, Hopi, Acoma, and the Rarámuri (in Mexico). Apache peoples migrated into the Mogollon area after the 15th century—around the time that the Mogollon stopped appearing in the archaeological record.

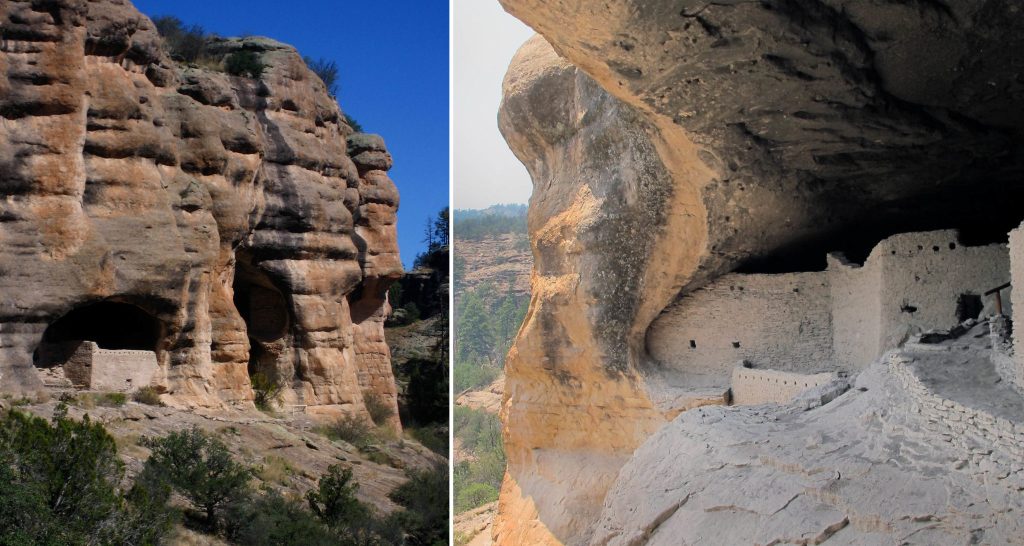

Architecture

Existing archaeological evidence indicates that early on, small Mogollon communities were clustered on hilltops in pithouses. These were circular or oval rooms dug into the ground, which helped to maintain a comfortable temperature. Mogollon people practiced agriculture (primarily growing maize, beans, and squash), but also relied on hunting and foraging. Around the year 1000, Mogollon peoples began to build above ground and made square living spaces. We also find large round ceremonial rooms that have been called “great kivas” beginning around 850, and which could accommodate large gatherings.

Shared forms, including architectural features, identifiable among the Mogollon, Ancestral Puebloan, and Hohokam peoples indicate they interacted. Sites like Kinishba and Gila Cliff Dwellings (began after 1270) show the influence of Puebloan architectural features. For example, rather than pithouses, we now find above-ground villages built with stone as well as cliff dwellings—both characteristic of their Pueblo neighbors.

Paquimé

The city of Paquimé, largely built of adobe, would have rivaled other large cities and settlements of the region such as Chaco (which flourished earlier). It had large plazas and marketplaces; big domestic, multistory structures to accommodate its once sizable population (some buildings had 1000+ rooms); at least two ball courts; and platform mounds. One mound, called the Mound of the Cross, has a cross-shaped platform that is oriented toward the four cardinal directions, suggesting it played an astronomical or calendrical role perhaps to track equinoxes and solstices. The exact function of most mounds remains unknown. Feasting areas are filled with huge ovens to be able to cook for large numbers of people. A complex water system brought water from miles away to a reservoir, from where water flowed to the city.

There is clear evidence for long-distance trade with Mesoamerica and the influence of ideas and practices (such as the ballgame), but also trade with coastal regions and those to the east. Macaws, brought from far south, were not only brought here, but the people of Paquimé bred them as revealed by pens found along the plazas (turkeys were also bred here).

Paquimé was the largest, most complex city associated with the Mogollon tradition.

Mimbres pottery

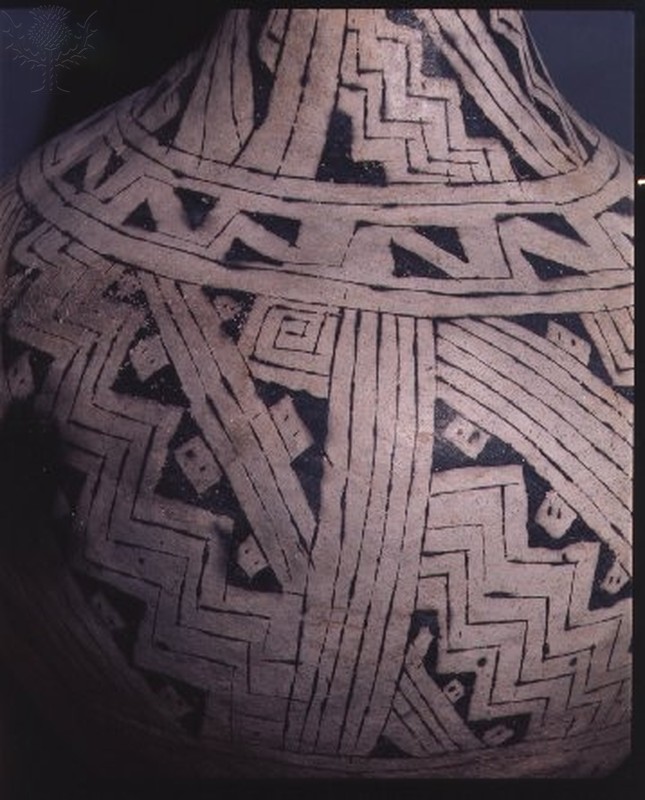

Mogollon ceramics are some of the finest examples of pottery from the Greater Southwest region.

There are different types of Mogollon pottery, but the tradition associated with Mimbres culture is the most well-known. Classic Mimbres pottery (1000–1150) has some of the most inventive and diverse subject matter depicted on it, ranging from geometric patterns to narratives with figures; the latter have sometimes been called “story bowls.” Animals and birds of wonderful variety grace the bowls, as do humans who fight, farm, hunt, give birth, and many other activities. Hybrid or sacred creatures, such as horned serpents or animal-human hybrids adorn Mimbres pottery.

Typically painted on hemispheric bowls, Mimbres pottery survives in great numbers—more than 10,000 bowls survive—and many are found largely intact. The bowls were found in burials, and many Mimbres bowls show light wear-and-tear, suggesting they were used (possibly in food preparation) before going underground.

Many Mimbres bowls show light wear-and-tear, suggesting they were used (possibly in food preparation) before going underground. Most of the bowls have a hole in the base of the bowl, such as we see in the bottom of the scorpion bowl. While we do not know the exact purpose of the hole, two possibilities are that it aided the soul of the deceased by providing a path or that the hole silenced the life force or spirit of the bowl. The bowl was often placed over the face of the deceased, which echoes contemporary Pueblo accounts of the dead going to the dome of the sky as spirits.[1]

Petroglyphs and rock paintings

The Mogollon peoples also produced a great deal of rock art, such as at Three Rivers Petroglyph site where there are more than 20,000 petroglyphs made between 900–1400.

At Hueco Tanks, sacred for the Jornada branch most likely, we find pictographs and paintings that adorn the walls of caves, such as birds, humans, and what are identified as masks. Many of the figures have been compared to Mesoamerican deities such as Quetzalcoatl and Tlaloc because they seem to have goggle eyes or feathered/horned serpents; as was discussed above though, figures like horned serpents were important to peoples across the Greater Southwest.

Multiple descendant groups still consider Hueco Tanks a sacred place; it is one of many footprints in the region that connect contemporary communities with their ancestors.

Video

Speaking to both the Past and the Present: Clarissa Rizal’s Resilience Robe (6:19)

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Map of North America showing the regions of Native American cultures (Image source: Khan Academy) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 2. Map of Indian Lands in the United States; Indian Lands of Federally Recognized Tribes of the United States (June 2016) (Contributors: U.S. Department of Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs; Image source: Data.gov) is licensed under a Public Domain license

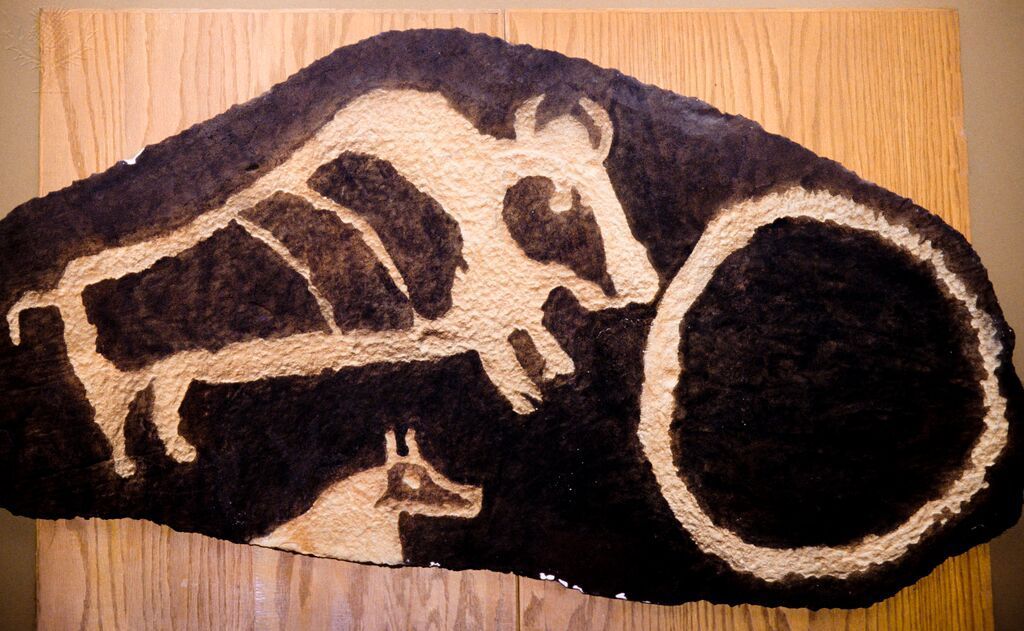

- Figure 3. Ute petroglyph rock art carving of a buffalo, horse and hoop symbols, Vernal, Utah (Image source: Britannica Image Quest, Native stock / UIG. Rights managed / For education only)

- Figure 4. Head-dress previously owned by Chief Yellow Calf from Teethe, Wyoming, early 20th century, immature tail feathers of a golden eagle, horse hair, beads, ermine, cloth, Arapaho, 75 cm high (Image source: © The Trustees of the British Museum. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 5. Naming artist (of the Kwakiutl), Thunderbird Mask, 19th c., from Alert Bay, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, cedar, pigment, leather, nails, metal plate, (closed). Brooklyn Museum, NY (Image source: Steven Zucker via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 6. Ulu (or woman’s knife) with a musk ox horn handle, Inuit, early 19th century C.E., copper, 29 cm wide, from Coronation Gulf, Canada (Image source: © Trustees of the British Museum. Used with permission, for education only)

- Figure 7. Sledge made of bone, ivory, sealskin, wood, and sinew, Greenland, ca 1818 (Image source: © Trustees of the British Museum. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 8. Mongol/Anastasia pottery vase with geometric design, 1000 A.D. From the Museum of Canyon De Chelly, Arizona (Image source: Britannica Image Quest, Werner Foreman / Universal Images Group. Rights Managers Bundle / For education use only)

- Figure 9. Regions of ancient regional tribes in the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico (Image source: Ricraider via Smarthistory) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 10. Gila Cliff Dwellings is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 11. Bowl with scorpions, c. 950–1150 C.E., Mogollon (Mimbres), ceramic and pigment, 14.9 cm high, 34.6 cm in diameter (Image source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art via Smarthistory)

- Figure 12. Left: María Martinez and Popovi Da (both from San Ildefonso Pueblo), Plate with radiating feather design, 1960s, ceramic, 5.08 cm high, 40.64 cm in diameter; right: Bowl, Mogollon (Mimbres), c. 1000–1150, ceramic, slip, and paint, 15.6 cm high, 29.84 cm in diameter (Image source: Dallas Museum of Art via Smarthistory)

- Figure 13. Rock drawings, or pictographs, in a restricted area of Hueco Tanks State Historic Site near El Paso in El Paso County, Texas (Image source: photograph by Carol M. Highsmith; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division; accessed via Smarthistory)

Candela Citations

- Buffalo Robe. Authored by: Trustees of the British Museum. Provided by: Khan Academy. Retrieved from: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/native-north-america/native-american-west/a/buffalo-robe. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Native North America, an introduction. Authored by: Trustees of the British Museum. Provided by: Khan Academy. Retrieved from: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/beginners-guide-art-of-the-americas/native-american-art/a/native-north-america-an-introduction. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- About geography and chronological periods in Native American art. Authored by: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank. Provided by: Khan Academy. Retrieved from: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/native-north-america/beg-guide-native-am-1600/a/about-geography-and-chronological-periods-in-native-american-art. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Introduction to Mogollon. Authored by: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-mogollon/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Infinity of Nations - Art and History in the Collections of the National Museum of the American Indian. Provided by: National Museum of the American Indian (Smithsonian). Retrieved from: https://americanindian.si.edu/exhibitions/infinityofnations/southwest.html#objects. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: For educational use only

- Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 56. ↵