Chapter 11.9: Postmodern Art

Abstraction

Abstract art, also called non-objective art or non-representational art, painting, sculpture, or graphic art in which the portrayal of things from the visible world plays no part. All art consists largely of elements that can be called abstract—elements of form, color, line, tone, and texture. Prior to the 20th century these abstract elements were employed by artists to describe, illustrate, or reproduce the world of nature and of human civilization—and exposition dominated over expressive function. – Encyclopedia Britannica

Looking deeply

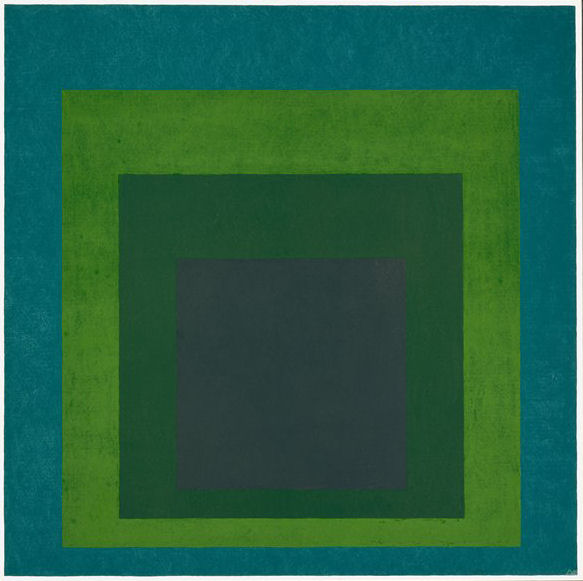

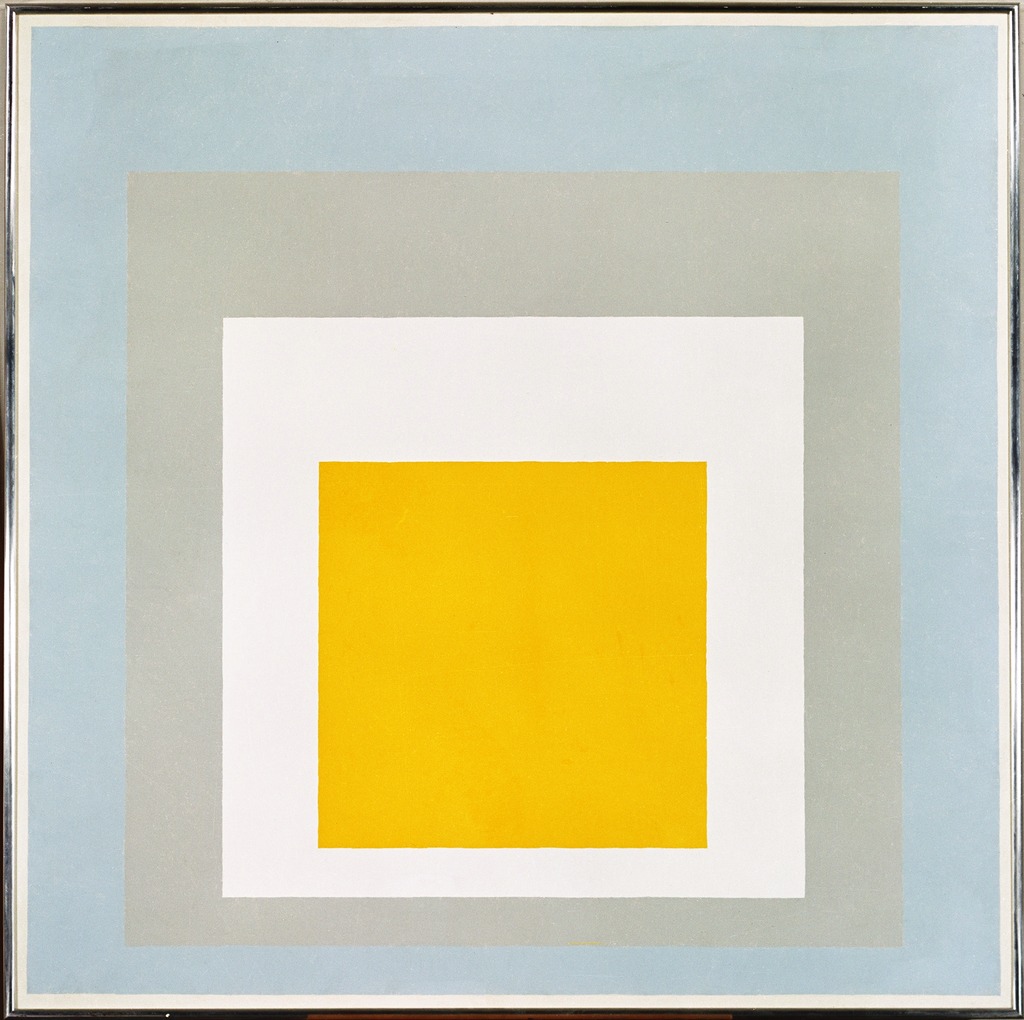

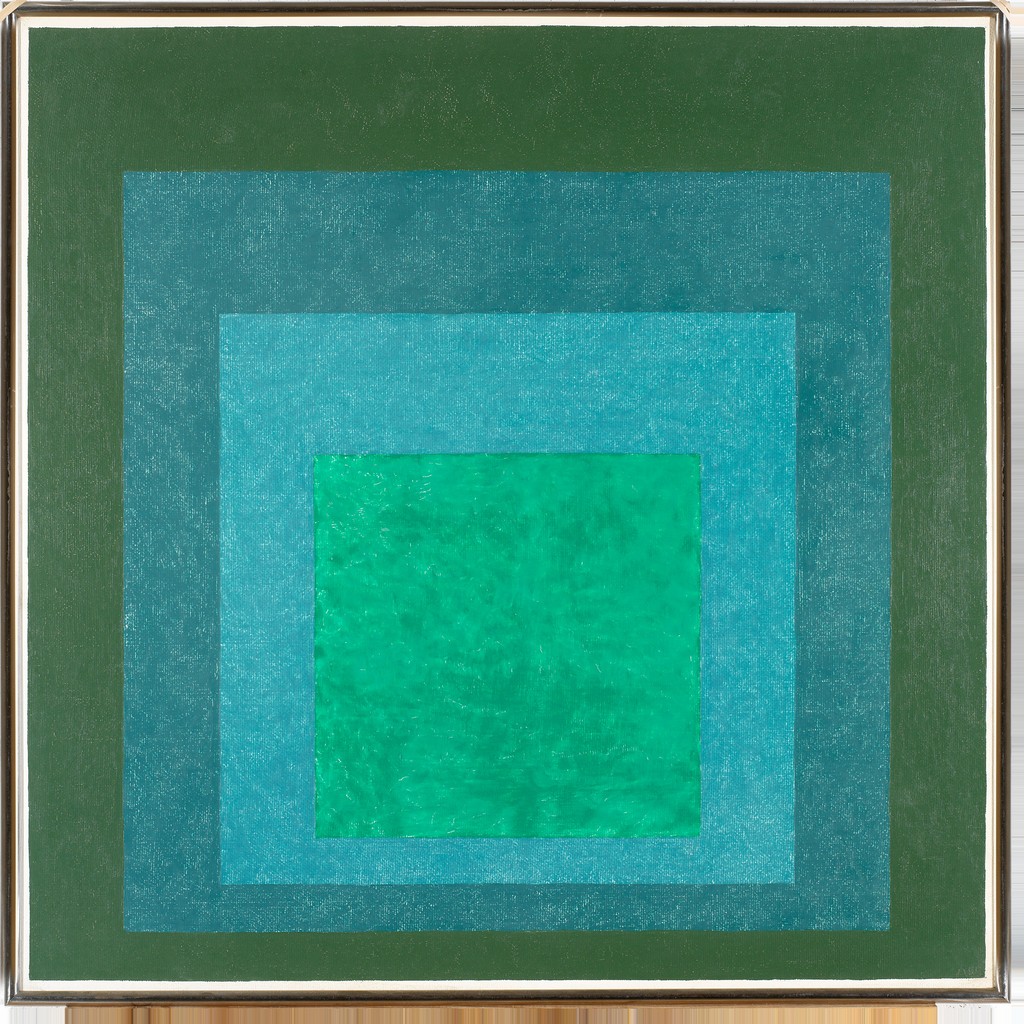

Take a moment to really look deeply at this example of Josef Albers’ extensive series, Homage to the Square. The composition of this painting is simple enough – four progressively smaller squares within each other, each in a different color, and all aligned closer to the bottom of the composition than to the top. So stand back from this Homage to the Square and look at the whole thing. What is the relationship between the squares? Are they stacked on top of each other, like cut out pieces of construction paper? Are they sinking underneath each other, as if you are looking at a painting of a tunnel? Do some appear to push toward you and others to fall away? And how does it change between each version of the painting? Looking at the pieces, you may find that you are able to force your eyes to see a stack of blocks or a tunnel, or you may find that you are instinctively drawn to one interpretation of how the squares are arranged.

This is exactly the principle that Albers experimented with as he produced hundreds of variations on this theme over a period of about 25 years. These included paintings, drawings, prints, and tapestries—but each explored the same basic question: can an artist create the appearance of three dimensions, using only color relations?

The Bauhaus

Though Albers began work on the Homage paintings in 1950, he was introduced to color theory very early in his career, when he enrolled as a student at the Bauhaus in 1920. The Bauhaus was a revolutionary school of art and design in Germany, founded by Walter Gropius in 1919. Its philosophy was to integrate the principles of fine art and functional design, and many of the most important artists in Europe were teachers there. When Albers was a student, the foundation for all Bauhaus education was the Vorkurs, or preliminary course, taught by Johannes Itten. The course covered the fundamentals of material, composition, and color theory, and was one of the most influential and widely disseminated aspects of Bauhaus curriculum.

Many studies done by students as part of the Vorkurs can be seen in museums and exhibitions, and they often bear a resemblance to Albers’ Homage paintings: a repeated series of shapes, each in different color combinations. The goal of these exercises was for the students to understand how colors related to each other. Many years later, Albers used the Homage paintings to go into even more depth with those lessons, and bring them to audiences, as well as art students.

From Dessau to Black Mountain

In 1925, the year that the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to their iconic building in Dessau, Gropius invited Albers to be the first student of the Bauhaus to join the faculty. Albers worked with Paul Klee in the stained glass workshop and was the longest-serving member of the faculty when the school was shut down by the Nazis in 1933. But the Bauhaus was to be only the first of Albers’ celebrated and influential teaching positions. When that school was shut down, Albers’ and his wife, Anni—herself an influential artist and Bauhaus alumna—emigrated to the United States, where he was invited to teach at the revolutionary Black Mountain College in North Carolina, and later Yale University, where he began the first Homage paintings in 1950. An encouraging but strict teacher, Albers brought Bauhaus ideas to a new country, introducing his disciplined approach to color theory to the next generation of the artistic vanguard in America.

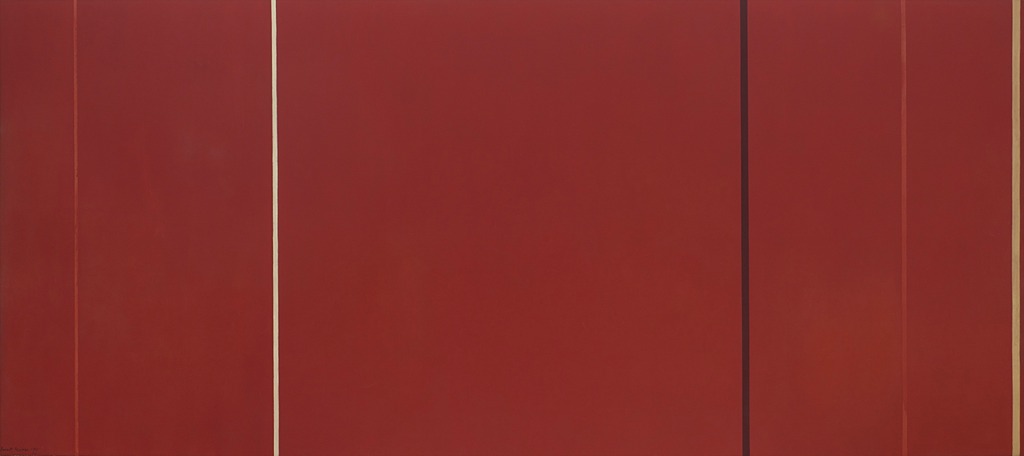

For all their variety of color, the Homage paintings are relatively cold and clinical. It is interesting to compare them to paintings by Mark Rothko, who produces canvasses that have strong similarities to the Homage series. Albers and Rothko both use roughly square or rectangular forms in solid colors, and both take the relationship between colors as their subject matter. But while Rothko’s paintings use variation of color to suggest or inspire certain emotional reactions, Albers’ paintings are exploring the creation of space through the use of color. He experiments with subverting the limits of two-dimensional space.

Tradition and variation

This technique had been used to create space in representative paintings going back to antiquity, but Albers was revolutionary in applying it to abstract art. His experiments in the Homage series paved the way for artists such as Bridget Riley and a whole generation of Op artists, who also pushed the limits of two-dimensional media by creating large-scale optical illusions. Though Homage to the Square may seem boring and repetitive to some, their simple beauty is often compared to classical music, like the work of Bach: a study on theme and variation.

Painters in Postwar New York City

The end of World War II was a pivotal moment in world history and by extension the history of art. Many European artists had come to America during the 1930s to escape fascist regimes, and years of warfare had left much of Europe in ruins. In this context New York City emerged as the most important cultural center in the West. In part, this was due to the presence of a diverse group of European artists like Arshile Gorky, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalì, Piet Mondrian, and Max Ernst, and the influential German teachers Josef Albers and Hans Hofmann (see also Black Mountain College). American artists’ exposure to European modernist movements also resulted from the founding of the Museum of Modern Art (1929), the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (later the Guggenheim Museum, 1939), and galleries that dealt in modern art, such as Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century (1941). Both Americans and European expatriates joined American Abstract Artists, a group that advanced abstract art in America through exhibitions, lectures, and publications.

These institutions and the art patrons affiliated with them actively promoted the work of New York City artists. During the 1940s and ’50s, the scene was dominated by the figures of Abstract Expressionism, a group of loosely affiliated painters participating in the first truly American modernist movement (sometimes called the New York School), championed by the influential critic Clement Greenberg. Abstract Expressionism’s influences were diverse: the murals of the Federal Art Project, in which many of the painters had participated, various European abstract movements, like De Stijl, and especially Surrealism, with its emphasis on the unconscious mind that paralleled Abstract Expressionists’ focus on the artist’s psyche and spontaneous technique. Abstract Expressionist painters rejected representational forms, seeking an art that communicated on a monumental scale the artist’s inner state in a universal visual language.

Abstract Expressionism

The group of artists known as Abstract Expressionists emerged in the United States in the years following World War II. As the term suggests, their work was characterized by non-objective imagery that appeared emotionally charged with personal meaning. The artists, however, rejected these implications of the name.

What’s in a name?

They insisted their subjects were not “abstract,” but rather primal images, deeply rooted in society’s collective unconscious. Their paintings did not express mere emotion. They communicated universal truths about the human condition. For these reasons, another term—the New York School—offers a more accurate descriptor of the group, for although some eventually relocated, their distinctive aesthetic first found form in New York City.

Action Painting

These painters fall into two broad groups: those who focused on a gestural application of paint, and those who used large areas of color as the basis of their compositions. The leading figures of the first group were Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner, and above all Jackson Pollock. Pollock’s innovative technique of dripping paint on canvas spread on the floor of his studio prompted critic Harold Rosenberg to coin the term action painting to describe this type of practice. Action painting arose from the understanding of the painted object as the result of artistic process, which, as the immediate expression of the artist’s identity, was the true work of art. Helen Frankenthaler also employed experimental techniques by pouring thinned pigments onto untreated canvas.

Videos

The Case for Jackson Pollock | The Art Assignment | PBS Digital Studios (11:15)

Frankenthaler, Mountains and Sea (4:30)

Color Field Painting

The second branch of Abstract Expressionist painting is usually referred to as Color Field painting. Two central figures in this group were Mark Rothko, known for canvases composed of two or three soft, rectangular forms stacked vertically, and Barnett Newman, who, in contrast to Rothko, painted fields of color with sharp edges interrupted by precise vertical stripes he called “zips” (see Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 1950–51, below). Through the overwhelming scale and intense color of their canvases, color Field painters like Rothko and Newman revived the Romantic aesthetic of the sublime.

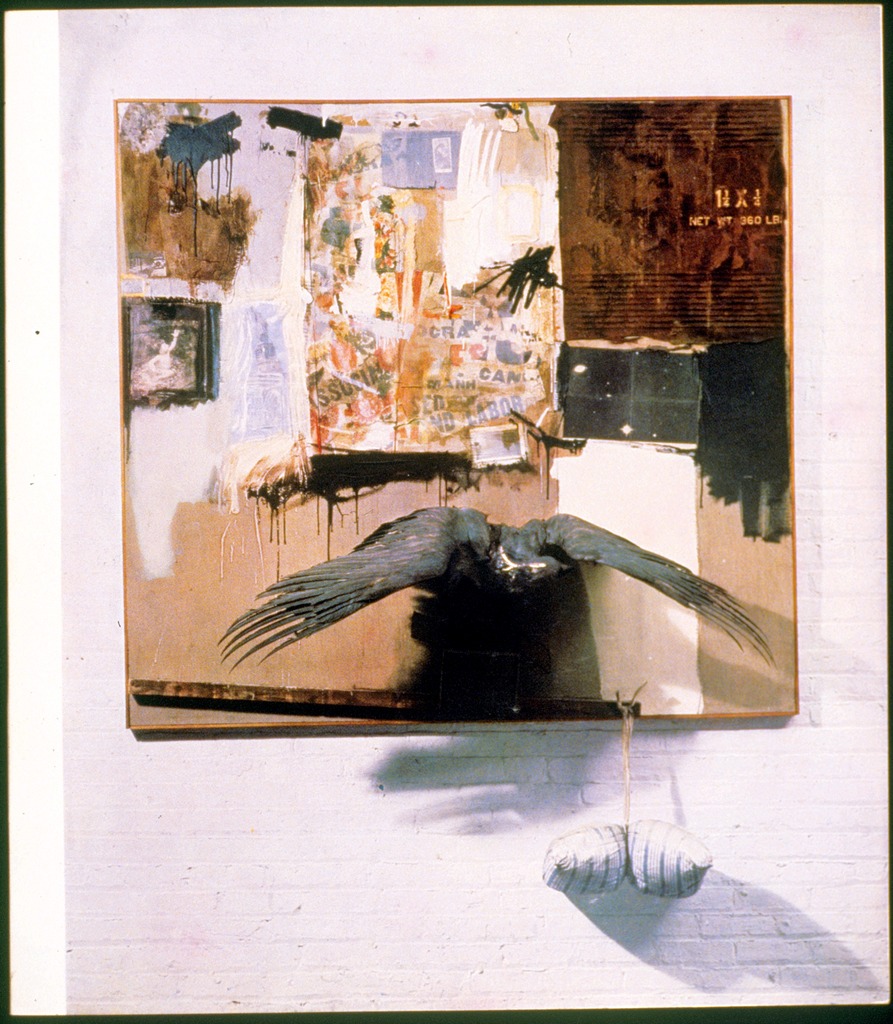

Assemblage – Combines

Is Canyon a painting or sculpture? Its upper half is a mass of materials that include bits of a shirt, printed paper, a squashed tube of paint, and photographs all seemingly held in place by broad slashes of house paint, while its lower half consists of a stuffed bald eagle with outstretched wings about to lift off from an opened box. The box seems to balance precariously upon a beam that tilts downward to the right; its end point meets the frame. As if that were not enough, that beams suspends a pillow dangling below the frame and squeezed in half by the cloth string that holds it.

Combines

Canyon belongs to a group of artworks called “Combines,” a term unique to this artist who attached extraneous materials and objects to canvases in the years between 1954 and 1965. What makes Rauschenberg so significant for this period—the postwar years—is how he challenged conventional ways of thinking about advanced modern art; especially the art of “The New York School,” a group of émigré Europeans and like-minded American artists (including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and their followers), who were praised for their heroic abstraction. Rauschenberg’s art violated the rules.

While the the word “Combine” has no known origin in an art context, it describes Rauschenberg’s hybrid approach to art making which dismantled the rigid medium-specific categories so dear to modernist culture. In the American art critic Clement Greenberg’s influential theory, so-called true painting was to explore only the properties inherent to painting: gesture, flatness and color. Sculpture was to adhere strictly to the delineation of volume and mass. Both would necessarily be abstract since the truth-to-materials maxim of post-war modernism meant that any kind of illusionism (bronze pretending to be flesh or paint attempting to resemble the thing it represented) was anathema. “Subject matter,” in Greenberg’s infamous declaration, “becomes something to be avoided like a plague.”1 With Canyon, like any number of Combines the artist created during this period, all of this was put into question. Not only did the artist subvert the distinction between painting and sculpture, he reintroduced subject matter and narrative back into art. The art historian Leo Steinberg declared that Rauschenberg’s Combines “let the world back in again.”2

Cultural Debris

Rauschenberg did know other artists who took a similar approach and challenged the narrow parameters of the formalists wing of the New York School and its rejection of popular culture and illusionism. His immediate circle included the painter Jasper Johns, the choreographer Merce Cunningham and the avant-garde composer John Cage. On the West Coast Edward Kienholz and Wallace Berman were creating artworks that would come to be called “Assemblage”—think collage on a large scale.

In Paris, Arman, Jean Tinguely and Jacques de la Villeglé incorporated the debris of the city; junk and cast off commodities incorporated into artworks that became known as Nouveau réalism (New realism).

Pop Art

Popular culture, “popular” art

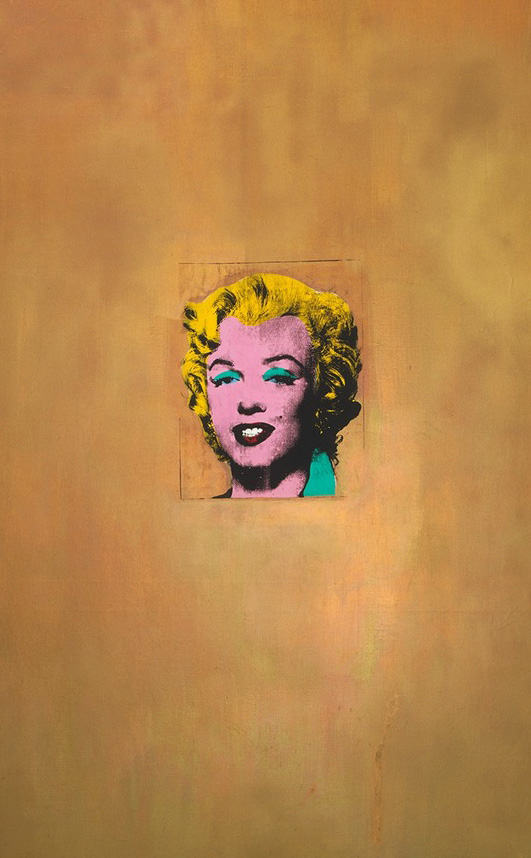

At first glance, Pop Art might seem to glorify popular culture by elevating soup cans, comic strips and hamburgers to the status of fine art on the walls of museums. But, then again, a second look may suggest a critique of the mass marketing practices and consumer culture that emerged in the United States after World War II. Andy Warhol’s Gold Marilyn Monroe(1962) clearly reflects this inherent irony of Pop. The central image on a gold background evokes a religious tradition of painted icons, transforming the Hollywood starlet into a Byzantine Madonna that reflects our obsession with celebrity. Notably, Warhol’s spiritual reference was especially poignant given Monroe’s suicide a few months earlier. Like religious fanatics, the actress’s fans worshipped their idol; yet, Warhol’s sloppy silk-screening calls attention to the artifice of Marilyn’s glamorous façade and places her alongside other mass-marketed commodities like a can of soup or a box of Brillo pads.

Genesis of Pop

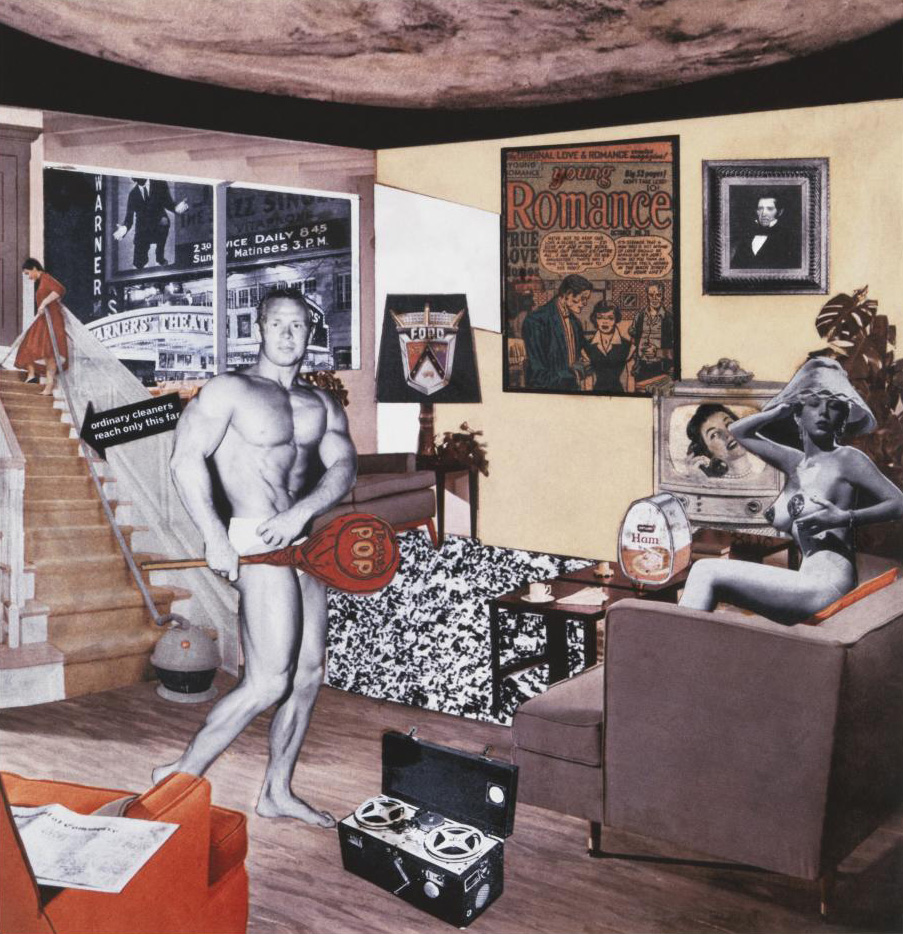

In this light, it’s not surprising that the term “Pop Art” first emerged in Great Britain, which suffered great economic hardship after the war. In the late 1940s, artists of the “Independent Group,” first began to appropriate idealized images of the American lifestyle they found in popular magazines as part of their critique of British society.

Critic Lawrence Alloway and artist Richard Hamilton are usually credited with coining the term, possibly in the context of Hamilton’s famous collage from 1956, Just what is it that makes today’s home so different, so appealing? (above) Made to announce the Independent Group’s 1956 exhibition “This Is Tomorrow,” in London, the image prominently features a muscular semi-nude man, holding a phallically positioned Tootsie Pop.

Pop Art’s origins, however, can be traced back even further. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp asserted that any object—including his notorious example of a urinal—could be art, as long as the artist intended it as such. Artists of the 1950s built on this notion to challenge boundaries distinguishing art from real life, in disciplines of music and dance, as well as visual art. Robert Rauschenberg’s desire to “work in the gap between art and life,” for example, led him to incorporate such objects as bed pillows, tires and even a stuffed goat in his “combine paintings” that merged features of painting and sculpture. Likewise, Claes Oldenburg created The Store, an installation in a vacant storefront where he sold crudely fashioned sculptures of brand-name consumer goods. These “Proto-pop” artists were, in part, reacting against the rigid critical structure and lofty philosophies surrounding Abstract Expressionism, the dominant art movement of the time; but their work also reflected the numerous social changes taking place around them.

Post-War Consumer Culture Grabs Hold (and Never Lets Go)

The years following World War II saw enormous growth in the American economy, which, combined with innovations in technology and the media, spawned a consumer culture with more leisure time and expendable income than ever before. The manufacturing industry that had expanded during the war now began to mass-produce everything from hairspray and washing machines to shiny new convertibles, which advertisers claimed all would bring ultimate joy to their owners. Significantly, the development of television, as well as changes in print advertising, placed new emphasis on graphic images and recognizable brand logos—something that we now take for granted in our visually saturated world.

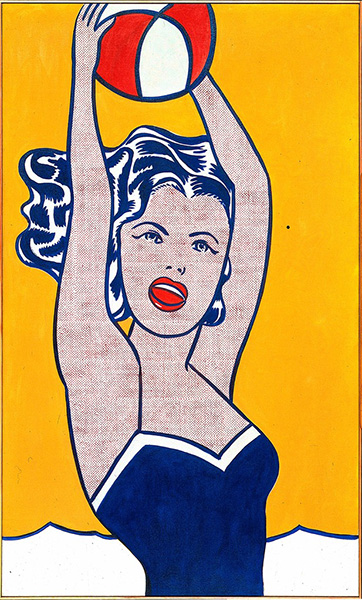

It was in this artistic and cultural context that Pop artists developed their distinctive style of the early 1960s. Characterized by clearly rendered images of popular subject matter, it seemed to assault the standards of modern painting, which had embraced abstraction as a reflection of universal truths and individual expression.

In contrast to the dripping paint and slashing brushstrokes of Abstract Expressionism—and even of Proto-Pop art—Pop artists applied their paint to imitate the look of industrial printing techniques. This ironic approach is exemplified by Lichtenstein’s methodically painted Benday dots, a mechanical process used to print pulp comics. As the decade progressed, artists shifted away from painting towards the use of industrial techniques. Warhol began making silkscreens, before removing himself further from the process by having others do the actual printing in his studio, aptly named “The Factory.” Similarly, Oldenburg abandoned his early installations and performances, to produce the large-scale sculptures of cake slices, lipsticks, and clothespins that he is best known for today.

Photorealism

Photo-realism, also called Super-realism, American art movement that began in the 1960s, taking photography as its inspiration. Photorealist painters created highly illusionistic images that referred not to nature but to the reproduced image. Artists such as Richard Estes, Ralph Goings, Audrey Flack, Robert Bechtle, and Chuck Close attempted to reproduce what the camera could record. Several sculptors, including the Americans Duane Hanson and John De Andrea, were also associated with this movement. Like the painters, who relied on photographs, the sculptors cast from live models and thereby achieved a simulated reality. Photo-realism grew out of the Pop and Minimalism movements that preceded it. Like Pop artists, the Photo-realists were interested in breaking down hierarchies of appropriate subject matter by including everyday scenes of commercial life—cars, shops, and signage, for example. Also, like them, the Photo-realists drew from advertising and commercial imagery. The Photo-realists’ use of an industrial or mechanical technique such as photography as the foundation for their work in order to create a detached and impersonal effect also had an affinity with both Pop and Minimalism. Yet many saw Photo-realism’s revival of illusionism as a challenge to the pared-down Minimalist aesthetic, and many perceived the movement as an attack on the important gains that had been made by modern abstract painting. – Encyclopedia Britannica

Meet Photorealistic artist Chuck Close in the video: Note to Self: Artist Chuck Close paves his own path.

The following video explores a photorealist painting of Gerhard Richter called “Betty”.

Video

Gerhard Richter, Betty (4:58)

Minimalism

A reductive abstract art

Although many works of art can be described as “minimal,” the name Minimalism refers specifically to a kind of reductive abstract art that emerged during the early 1960s. At the time, some critics preferred names like “ABC,” “Boring,” or “Literal” Art, and even “No-Art Nihilism,” which they believed best summed up the literal presentation and lack of expressive content characterizing this new aesthetic. While scholars have recently argued for a broader definition of Minimalism that would include artists in number of disciplines, the term remains closely linked to sculpture of the period.

Donald Judd’s Untitled (1969) is characteristic in its use of spare geometric forms, repeated to create a unified whole that calls attention to its physical size in relationship to the viewer. Like most Minimalists, Judd used industrial materials and processes to manufacture his work, but his preference for color and shiny surfaces distinguished him among the artists who pioneered the style.

Lack of apparent meaning

What most people find disturbing about Minimalism is its lack of any apparent meaning. Like Pop Art, which emerged simultaneously, Minimalism presented ordinary subject matter in a literal way that lacked expressive features or metaphorical content; likewise, the use of commercial processes smacked of mass production and seemed to reject traditional expectations of skill and originality in art. In these ways, both movements were, in part, a response to the dominance of Abstract Expressionism, which had held that painting conveys profound subjective meaning. However, whereas Pop artists depicted recognizable images from kitsch sources, the Minimalists exhibited their plywood boxes, fluorescent lights and concrete blocks directly on gallery floors, which seemed even more difficult to distinguish as “Art.” (One well-known story tells of an art dealer, who visited Carl Andre’s studio during the winter and unknowingly burned a sculpture for firewood while the artist was away.) Moreover, when asked to explain his black-striped paintings of 1959, Frank Stella responded, “What you see is what you see.” Stella’s comment implied that, not only was there no meaning, but that none was necessary to demonstrate the object’s artistic value.

Writings

Given these facts, it may seem odd to learn that hundreds of essays and books have been written about Minimalism, many by the artists themselves. It is significant that, although Minimalist art shares similar features, the artists associated with the movement developed their aesthetic ideas from variety of philosophical and artistic influences. Through their writings, Minimalist artists put forth distinctive positions about the work they produced. In addition to his role as a sculptor, Judd was a prominent art critic, and his reviews provide eloquent explanations of his intent—shared by Stella and Dan Flavin—to eliminate the illusionism and “subjective” decision-making of traditional painting. Robert Morris, whose sculpture was influenced by avant-garde dance and performance, published a series of texts, arguing for sculpture to be understood in physical and psychological terms; and, Sol LeWitt introduced the term Conceptual Art to explain the use of seriality and systemic structure in his cubic grid-like forms.

Legacy

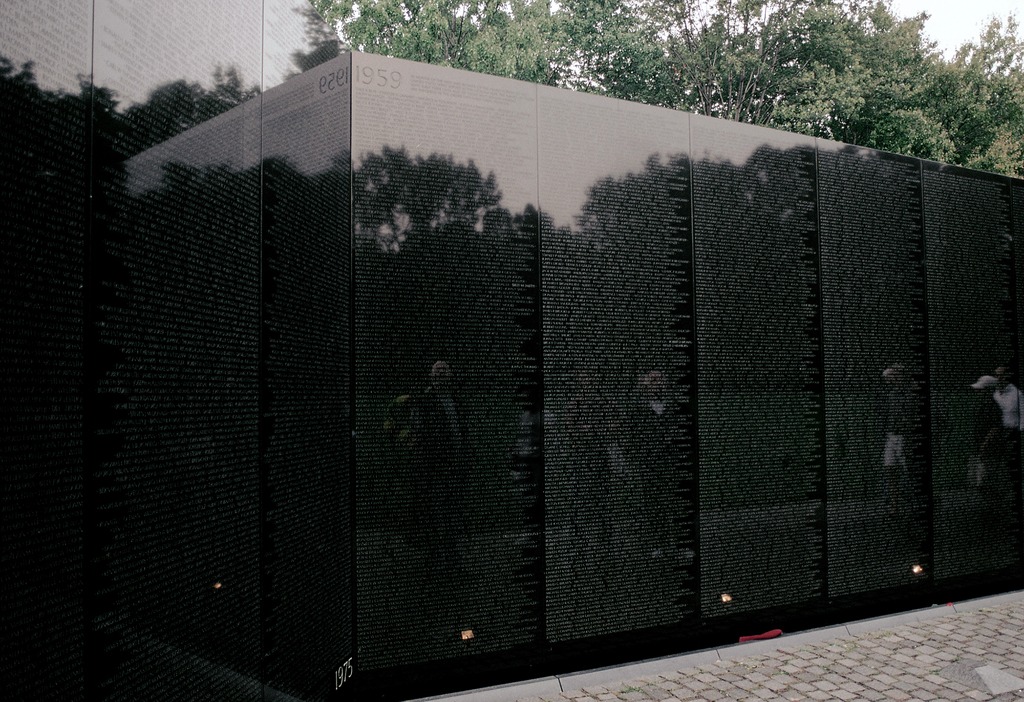

In this way, the artists, along with critics and art historians over the past 50 years, have developed a critical discourse that surrounds the art objects, but which is essential to understanding Minimalism itself. Likewise, such artists as Richard Serra, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Maya Lin and Rachel Whiteread, who use Minimalist practice of the early 1960s as a point of departure for their own creative exploration, continue to contribute to the movement’s legacy and our understanding of its significance today.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Josef Albers, Homage to the Square: Soft Spoken, 1969, oil on Masonite (Image source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the artist, 1972, Accession ID: 1972.40.7. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 2. Josef Albers, Homage to the Square “Ascending.” Oil on composition board, 1953 (Image source Carnegie Arts of the United States via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 3. Josef Albers, Study for Homage to the Square. Oil on artist board,1950 (Image source: Josef and Anni Albers Foundation via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 4. Mark Rothko, Orange and Red on Red, 1957, oil on canvas (Image source: The Phillips Collection via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 5. Mark Rothko, No. 16 (Red, Brown, and Black) with viewer (Image source: Steven Zucker via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 6. Barnett Newman, Vir Heroicus Sublimis. Oil on canvas, 1950-51 (Image source: The Museum of Modern Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 7. Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959, mixed media (Image source: Graphic Design Collection (The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art) via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 8. Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954, encaustic on canvas (Image source: The Museum of Modern Art, New York via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 9. Andy Warhol, Gold Marilyn Monroe, 1962, Silkscreen ink on synthetic polymer paint on canvas (Image source: The Museum of Modern Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 10. Richard Hamilton, Just what is it that makes today’s home so different, so appealing?, 1956, collage, 26 cm × 24.8 cm (10.25 in × 9.75 in) (Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany; Image source: Visual Arts Legacy Collection via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 11. Robert Rauschenberg, Bed, 1955, Oil and pencil on pillow, quilt, and sheet on wood supports (Image source: The Museum of Modern Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 12. Stylized Appliance Ad from Family Circle Magazine, January 1951, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Image source: Classic Film, via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Figure 13. Roy Lichtenstein, Girl with a Ball, 1961, oil on canvas (Image source: Roy Lichtenstein collection via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 14. Detail of face showing Lichtenstein’s painted Benday dots.

- Figure 15. Gerhard Richter, Betty, 1988, oil on canvas )Image source: Saint Louis Art Museum via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 16. Donald Judd, Untitled. Copper sculpture, ten units with 9-inch intervals, 1969 (Image source: ©The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 17. Maya Ying Lin, Vietnam War Memorial – The Wall, 1984, polished black marble. (Washington, D. C.; The Mall; Constitution Gardens; Image source: Harthill Art Associates via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

Candela Citations

- Josef Albers, Homage to the Square. Authored by: Shawn Roggenkamp. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/albers-homage-to-the-square/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Abstract Expressionism, an introduction. Authored by: Dr. Virginia B. Spivey. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/abstract-expressionism-an-introduction/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- The impact of Abstract Expressionism. Authored by: Oxford University Press. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/the-impact-of-abstract-expressionism/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon. Authored by: Dr. Thomas Folland. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/robert-rauschenberg-canyon/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- A-Level: Pop Art. Authored by: Dr. Virginia B. Spivey. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/pop-art-2/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- An introduction to Minimalism. Authored by: Dr. Virginia B. Spivey. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/an-introduction-to-minimalism/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Abstract Art. Authored by: The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Provided by: Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/art/abstract-art. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Used with permission, for educational use only

- Photo-realism. Authored by: Lisa S. Wainwright. Provided by: Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/art/Photo-realism. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Used with permission, for educational use only