Chapter 11.8: Modern Art: 1900s Until Now

Fauvism

Distinctive brushwork

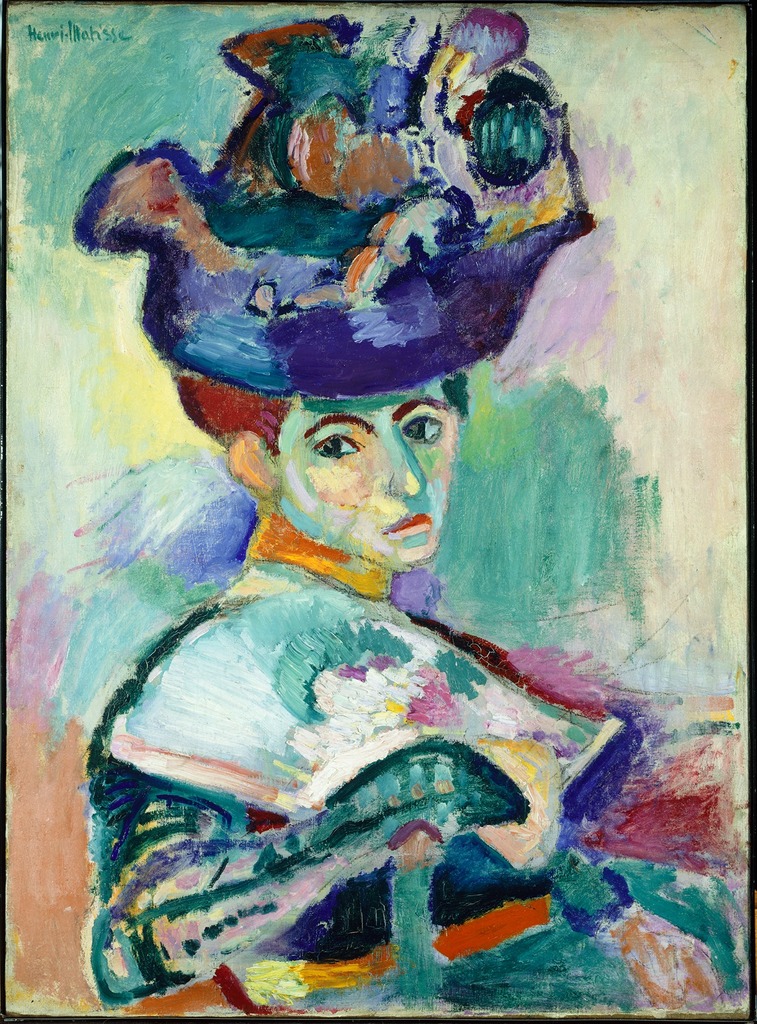

Fauvism developed in France to become the first new artistic style of the 20th century. In contrast to the dark, vaguely disturbing nature of much fin-de-siècle, or turn-of-the-century, Symbolist art, the Fauves produced bright cheery landscapes and figure paintings, characterized by pure vivid color and bold distinctive brushwork.

“Wild beasts”

When shown at the 1905 Salon d’Automne (an exhibition organized by artists in response to the conservative policies of the official exhibitions, or salons) in Paris, the contrast to traditional art was so striking it led critic Louis Vauxcelles to describe the artists as “Les Fauves” or “wild beasts,” and thus the name was born.

One of several Expressionist movements to emerge in the early 20th century, Fauvism was short-lived, and by 1910, artists in the group had diverged toward more individual interests. Nevertheless, Fauvism remains significant for it demonstrated modern art’s ability to evoke intensely emotional reactions through radical visual form.

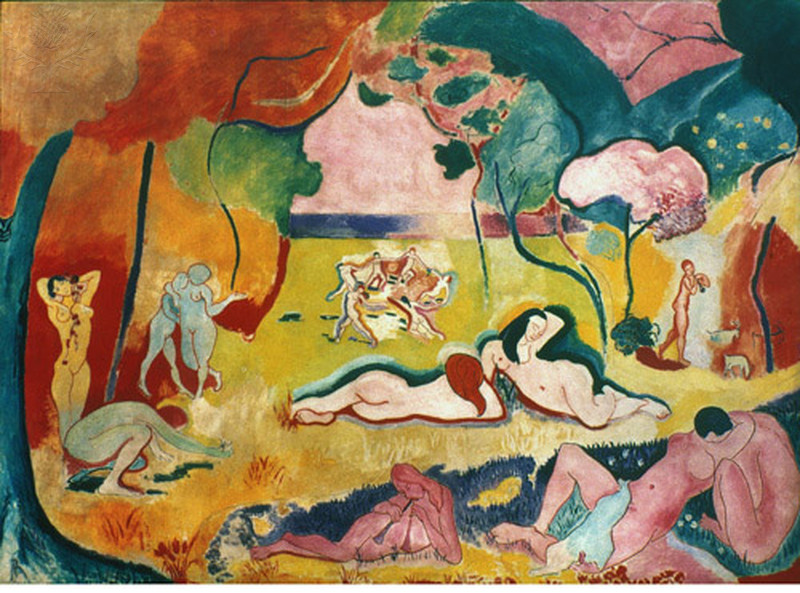

Paintings such as Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre (1905-06) epitomize this goal. Bright colors and undulating lines pull our eye gently through the idyllic scene, encouraging us to imagine feeling the warmth of the sun, the cool of the grass, the soft touch of a caress, and the passion of a kiss.

Like many modern artists, the Fauves also found inspiration in objects from Africa and other non-Western cultures. Seen through a colonialist lens, the formal distinctions of African art reflected current notions of Primitivism–the belief that, lacking the corrupting influence of European civilization, non-Western peoples were more in tune with the primal elements of nature.

Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra) of 1907 shows how Matisse combined his traditional subject of the female nude with the influence of primitive sources. The woman’s face appears mask-like in the use of strong outlines and harsh contrasts of light and dark, and the hard lines of her body recall the angled planar surfaces common to African sculpture. This distorted effect, further heightened by her contorted pose, clearly distinguishes the figure from the idealized odalisques of Ingres and painters of the past.

Expressionism

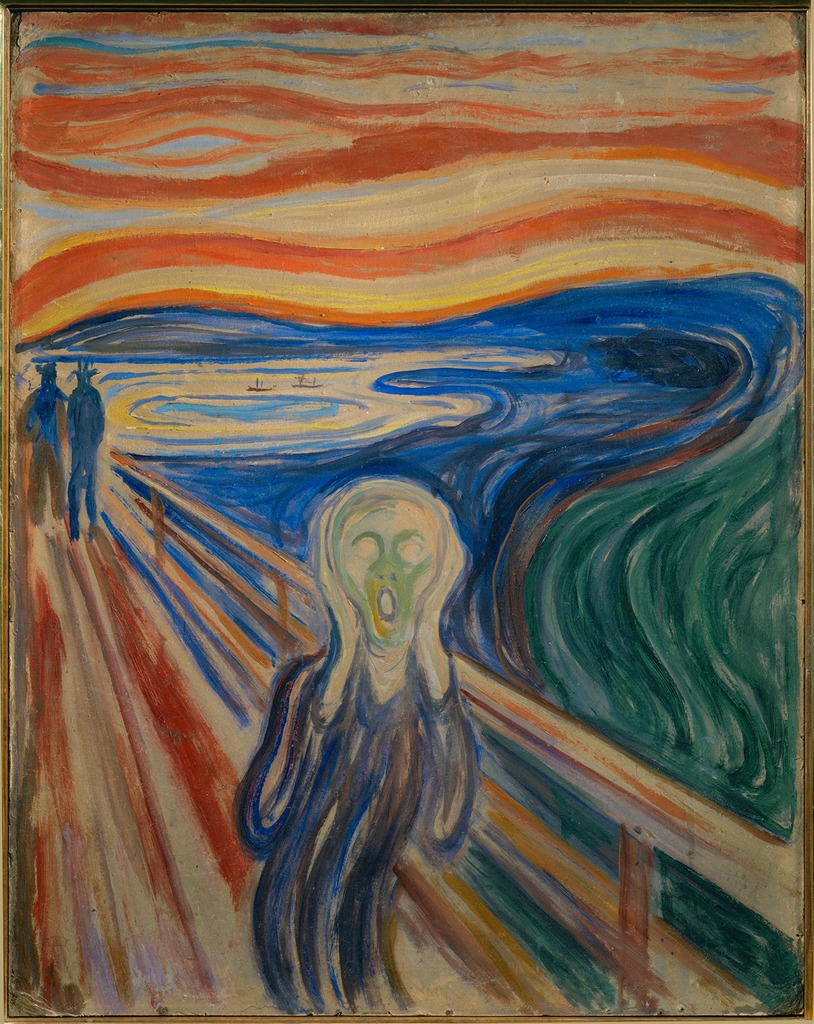

Imagine a painting where the magentas scream, the greens glare, and coarse brushstrokes become more ominous the longer you look at them. Paintings like this, where the artist uses color, line, and visible techniques to evoke powerful responses from the viewer date from the early twentieth century but continue expressive traditions that can be found throughout arts’ history. When capitalized as “Expressionism,” however, the term refers more specifically to an artistic tendency that became popular throughout Europe in the early twentieth century.

Like many categories in art history, Expressionism was not a name coined by artists themselves. It first emerged around 1910 as a way to classify art that shared common stylistic traits and seemed to emphasize emotional impact over descriptive accuracy. For this reason, artists like Edvard Munch straddle the line between Post-Impressionist developments in late 19th century painting and early 20th century Expressionism. Likewise, the Fauves in France exhibited similar characteristics in their work and are often linked to Expressionism.

Expressionism in Germany

Though many artists of the early twentieth century can accurately be called Expressionists, two groups that developed in Germany, Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), are among the best known and help to define the style. Instead of depicting the visible exterior of their subjects, they sought to express profound emotional experience through their art. German Expressionists, like other European artists of the time, found inspiration in so-called “primitive” sources that included African art, as well as European medieval and folk art and others untrained in Western artistic traditions. For the Expressionists, these sources offered alternatives to established conventions of European art and suggested a more authentic creative impulse.

Die Brücke

In 1905, four young artists working in Dresden and Berlin, joined together, calling themselves Die Brücke (The Bridge). Led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, the group wanted to create a radical art that could speak to modern audiences, which they characterized as young, vital, and urban. Drawn from the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, the nineteenth-century German philosopher, the name “Die Brücke” describes their desire to serve as a bridge from the present to the future.

While each artist had his own personal style, Die Brücke art is characterized by bright, often arbitrary colors and a “primitive” aesthetic, inspired by both African and European medieval art. Their work often addressed modern urban themes of alienation and anxiety, and sexually charged themes in their depictions of the female nude.

Der Blaue Reiter

Based in the German city of Munich, the group known as Der Blaue Reiter lasted only from their first exhibition at the Galerie Thannhausen in 1911 to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Die Blaue Reiter took its name from the motif of a horse and rider, often used by founding member Vasily Kandinsky.

In contrast to Die Brücke, whose subjects were physical and direct, Kandinsky and other Die Blaue Reiter artists explored the spiritual in their art, which often included symbolism and allusions to ethereal concerns. They thought these ideas could be communicated directly through formal elements of color and line, that, like music, could evoke an emotional response in the viewer. Conceived by Kandinsky and Franz Marc, the range of content shows Der Blaue Reiter’s efforts to provide a philosophical approach not just for the visual arts, but for culture more broadly. These ideas would become more fully developed at the Bauhaus where Kandinsky taught after the war (Marc died during the Battle of Verdun in 1916).

Videos

1913 | “Klänge (Sounds)” by Vasily Kandinsky (2:13)

Helen Mirren on Vasily Kandinsky (4:29)

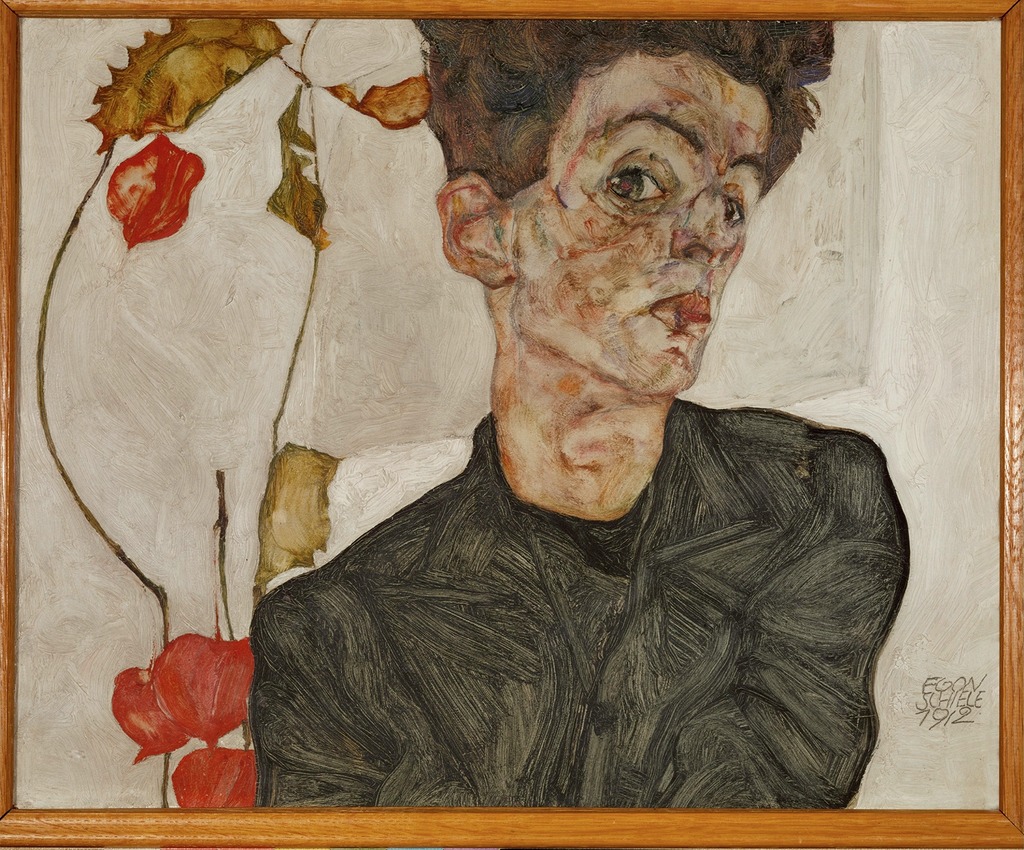

Austrian Expressionism

While the Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter groups had relatively defined memberships, Expressionist artists also worked independently. In Vienna, Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele stand out for paintings that show intense, often violent feeling and for their efforts to represent deeper psychological meaning.

In the aftermath of the First World War, many artists in Germany felt that the forceful emotional style of Expressionism that had been so progressive before the war but had become less appropriate. Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) arose as a direct response to pre-war stylistic excess.

Cubism

During the summer of 1908, Braque returned to Cézanne’s old haunt for a second summer in a row. Previously he had painted this small port just south of Aix-en-Provence with the brilliant irreverent colors of a Fauve (Braque along with Matisse, Derain, and others defined this style from about 1904 to 1907). But now, after Cézanne’s death and after having met Picasso, Braque set out on a very different tack, the invention of Cubism.

Cubism is a terrible name. Except for a very brief moment, the style has nothing to do with cubes. Instead, it is an extension of the formal ideas developed by Cézanne and broader perceptual ideas that became increasingly important in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These were the ideas that inspired Matisse as early as 1904 and Picasso perhaps a year or two later.

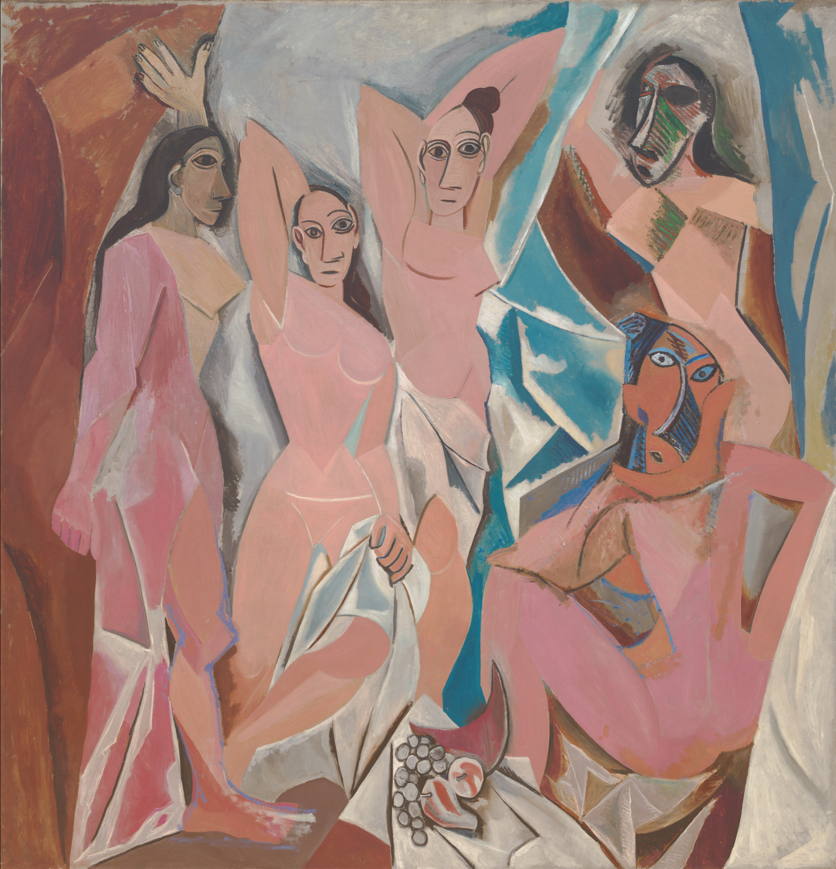

We certainly saw such issues asserted in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. But Picasso’s great 1907 canvas is not yet Cubism. It is more accurate to say that it is the foundation upon which Cubism is constructed. If we want to really see the origin of the style, we need to look beyond Picasso to his new friend Georges Braque.

A New Perspective

The young French Fauvist, Georges Braque that had been struck by both the posthumous Cézanne retrospective exhibition held in Paris in 1907 and his first sight of Picasso’s radical new canvas, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Like so many people that saw it, Braque is reported to have hated it—Matisse, for example, predicted that Picasso would be found hanged behind the work, so great was his mistake. Nevertheless, Braque stated that it haunted him through the winter of 1908. Like every good Parisian, Braque fled Paris in the summer and decided to return to the part of Provence in which Cézanne had lived and worked. Braque spent the summer of 1908 shedding the colors of Fauvism and exploring the structural issues that had consumed Cézanne and now Picasso. He wrote:

“It [Cézanne’s impact] was more than an influence, it was an invitation. Cézanne was the first to have broken away from erudite, mechanized perspective…”

Like Cézanne, Braque sought to undermine the illusion of depth by forcing the viewer to recognize the canvas not as a window but as it truly is, a vertical curtain that hangs before us. In canvases such as Houses at L’Estaque ( 1908), Braque simplifies the form of the houses (here are the so-called cubes), but he nullifies the obvious recessionary overlapping with the trees that force forward even the most distant building.

Brothers of Invention

When Braque returned to Paris in late August, he found Picasso an eager audience. Almost immediately, Picasso began to exploit Braque’s investigations. But far from being the end of their working relationship, this exchange becomes the first in a series of collaborations that lasts six years and creates an intimate creative bond between these two artists that is unique in the history of art.

Between the years 1908 and the beginning of the First World War in 1914, Braque and Picasso work together so closely that even experts can have difficulty telling the work of one artist from the other. For months on end they would visit each others studio on an almost daily basis sharing ideas and challenging each other as they went. Still, a pattern did emerge and it tended to be to Picasso’s benefit. When a radical new idea was introduced, more than likely, it was Braque that recognized its value. But it was inevitably Picasso who realized its potential and was able to fully exploit it.

Tough Art

By 1910, Cubism had matured into a complex system that is seemingly so esoteric that it appears to have rejected all esthetic concerns. The average museum visitor, when confronted by a 1910 or 1911 canvas by Braque or Picasso, the period known as Analytic Cubism, often looks somewhat put upon even while they may acknowledge the importance of such work. I suspect that the difficulty, is, well…, the difficulty of the work. Cubism is an analysis of vision and of its representation and it is challenging. As a society we seem to believe that all art ought to be easily understandable or at least beautiful. That’s the part I find confusing.

Videos

Pablo Picasso and the new language of Cubism (4:48)

What is Cubism? Pablo Picasso’s Three Musicians at the MoMA (6:53)

Futurism

Futurism, Italian Futurismo, Russian Futurism, early 20th-century artistic movement centred in Italy that emphasized the dynamism, speed, energy, and power of the machine and the vitality, change, and restlessness of modern life.

Can you imagine being so enthusiastic about technology that you name your daughter Propeller? Today we take most technological advances for granted, but at the turn of the last century, innovations like electricity, x-rays, radio waves, automobiles and airplanes were extremely exciting. Italy lagged Britain, France, Germany, and the United States in the pace of its industrial development. Culturally speaking, the country’s artistic reputation was grounded in Ancient, Renaissance and Baroque art and culture. Simply put, Italy represented the past.

In the early 1900s, a group of young and rebellious Italian writers and artists emerged determined to celebrate industrialization. They were frustrated by Italy’s declining status and believed that the “Machine Age” would result in an entirely new world order and even a renewed consciousness.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the ringleader of this group, called the movement Futurism. Its members sought to capture the idea of modernity, the sensations and aesthetics of speed, movement, and industrial development.

The Futurists were particularly excited by the works of late 19th-century scientist and photographer Étienne-Jules Marey, whose chronophotographic (time-based) studies depicted the mechanics of animal and human movement.

A precursor to cinema, Marey’s innovative experiments with time-lapse photography were especially influential for Balla. In his painting Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, the artist playfully renders the dog’s (and dog walker’s) feet as continuous movements through space over time.

Entranced by the idea of the “dynamic,” the Futurists sought to represent an object’s sensations, rhythms and movements in their images, poems and manifestos. Although Futurism continued to develop new areas of focus (aeropittura, for example) and attracted new members—the so-called “second generation” of Futurist artists—the movement’s strong ties to Fascism has complicated the study of this historically significant art.

Dada

Art as provocation

When you look at Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, a factory-produced urinal he submitted as a sculpture to the 1917 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York, you might wonder just why this work of art has such a prominent place in art history books. You would not be alone in asking this question. In fact, from the moment Duchamp purchased the urinal, flipped it on its side, signed it with a pseudonym (the false name of R. Mutt), and attempted to display it as art, the piece has generated controversy. This was the artist’s intention all along—to puzzle, amuse, and provoke his viewers.

Fountain was submitted to the Society of Independent Artists, one of the first venues for experimental art in the United States. It is a new form of art Duchamp called the “readymade”— a mass-produced or found object that the artist transformed into art by the operation of selection and naming. The readymades challenged the very idea of artistic production, and what constitutes art in a gallery or museum. Duchamp provoked his viewers—testing the the exhibition organizers’ liberal claim to accept all works with “no judge, no prize” without the conservative bias that made it difficult to exhibit modern art in most museums and galleries. Duchamp’s Fountain did more than test the validity of this claim: it prompted questions about what we mean by art altogether—and who gets to decide what art is.

Video

Art as concept: Duchamp, In Advance of the Broken Arm (10:08)

Surrealism

Psychic freedom Historians typically introduce Surrealism as an offshoot of Dada. In the early 1920s, writers such as André Breton and Louis Aragon became involved with Parisian Dada. Although they shared the group’s interest in anarchy and revolution, they felt Dada lacked clear direction for political action. So in late 1922, this growing group of radicals left Dada, and began looking to the mind as a source of social liberation. Influenced by French psychology and the work of Sigmund Freud, they experimented with practices that allowed them to explore subconscious thought and identity and bypass restrictions placed on people by social convention. For example, societal norms mandate that suddenly screaming expletives at a group of strangers—unprovoked, is completely unacceptable.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Portrait of Madame Matisse; La Raie Verte (The Green Line) by Henri Matisse. 1905, oil on cannvas. A portrait of Henri Matisse’s’ wife (Image source: Statens Museum for Kunst, National Gallery of Denmark. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 2. Henri Matisse, Femme au chapeau (Woman with a Hat), 1905, oil on canvas. (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Image source: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 3. Henri Matisse, Le Bonheur de vivre (Joy of Life), 1905-1906, oil on canvas (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, The Granger Collection / Universal Images Group. Rights Managed / For Education Use Only)

- Figure 4. Henri Matisse, The Blue Nude, 1907, oil on canvas (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 5. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Reclining Nude, 1909-1910, oil on canvas (Image source: University of California, San Diego via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 6. Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1910, tempera on cardboard (Image source: Minneapolis College of Art and Design Collection via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 7. Erich Heckel, Fränzi Reclining, 1910, woodcut in red and black (Image source: Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 8. Wassily Kandinsky, Lyrisches (Lyrical), from “Klänge” (Sounds), 1911, Color woodcut on cream laid Holland van Gelder paper (Image source: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 9. Franz Marc, Large Blue Horses, 1911, oil on canvas (Image source: University of California, San Diego via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 10. Egon Schiele, Self-portrait with Chinese Lantern and Fruits, 1912, oil and body color on wood. (Leopold Museum, Vienna; Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 11. Georges Braque, Landscape at La Ciotat, 1906-1907, oil on canvas. (Musée d’Art moderne, Troyes, France; Image source: Art Institute of Chicago via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 12. Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, oil on canvas (Image source: The Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism (ARS) via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 13. Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1902-1904, oil on canvas (Image source: Philadelphia Museum of Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Title: Houses at L’Estaque; Image ID: AIC_780030

- Figure 15. Pablo Picasso, The Reservoir, Horta de Ebro, 1909, oil on canvas (Image source: Museum of Modern Art, New York, fractional and promised gift. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 16. Georges Braque, The Portuguese, 1911, oil on canvas. (Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland; Image source: Allan T. Kohl, Minneapolis College of Art and Design via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 17. Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913, bronze sculpture. (Milan, Italy; Civico museo d’arte contemporanea; Image source: SCALA, Florence/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 18. Giacomo Balla, Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, 1912, oil on canvas. (Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Image source: Artwork Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. Image courtesy of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery Digital Assets Collection via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 19. Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917, urinal. (Exhibited at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, Spring 1988; Image source: Larry Qualls Archive: Contemporary Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 20. Marcel Jean, Spector of the Gardenia, 1936, Plaster head with painted black cloth, zippers, and strip of film on velvet-covered wood base (Image source: The Museum of Modern Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

Candela Citations

- Fauvism, an introduction. Authored by: Dr. Virginia B. Spivey. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/a-beginners-guide-to-fauvism/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Expressionism, an introduction. Authored by: Shawn Roggenkamp. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/expressionism-intro/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Braque, The Viaduct at Lu2019Estaque. Authored by: Extended Learning Institute of Northern Virginia Community College. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Retrieved from: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-arthistory2/chapter/braque-the-viaduct-at-lestaque/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Pablo Picasso and the new language of Cubism. Authored by: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/picasso-guitar/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Italian Futurism: An Introduction. Authored by: Emily Casden. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/italian-futurism-an-introduction/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Introduction to Dada. Authored by: Dr. Stephanie Chadwick. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-dada/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Surrealism, an introduction. Authored by: Josh R. Rose. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/surrealism-intro/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike