Chapter 11.6: Impressionism and Japonism

The Impressionists are all followers of Realism, but they also will organize 8 exhibitions together and paint in a brand new style. Instead of painting an ideal of beauty, the impressionists tried to depict what they saw at a given moment, capturing a fresh, original vision.

They often painted out of doors so that they could observe nature more directly and set down its most fleeting aspects—especially the changing light of the sun. Some of the Artists involved: Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cezanne, Paul Signac, Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, Georges Seurat.

The Impressionist movement is also heavily influenced by the invention of the paint tube, without which artists would have never found the freedom to paint out of doors.

Video

Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (6:14)

Apart From the Salon

The group of artists who became known as the Impressionists did something groundbreaking in addition to painting their sketchy, light-filled canvases: they established their own exhibition. This may not seem like much in an era like ours, when art galleries are everywhere in major cities, but in Paris at this time, there was one official, state-sponsored exhibition—called the Salon—and very few art galleries devoted to the work of living artists. For most of the nineteenth century then, the Salon was the only way to exhibit your work (and therefore the only way to establish your reputation and make a living as an artist). The works exhibited at the Salon were chosen by a jury—which could often be quite arbitrary. The artists we know today as Impressionists—Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Alfred Sisley (and several others)—could not afford to wait for France to accept their work. They all had experienced rejection by the Salon jury in recent years and felt that waiting an entire year between exhibitions was too long. They needed to show their work and they wanted to sell it.

The artists pooled their money, rented a studio that belonged to the photographer Nadar, and set a date for their first collective exhibition. They called themselves the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Printmakers and their first show opened at about the same time as the annual Salon in May 1874. The Impressionists held eight exhibitions from 1874 through 1886.

The impressionists regarded Manet as their inspiration and leader in their spirit of revolution, but Manet had no desire to join their cooperative venture into independent exhibitions. Manet had set up his own pavilion during the 1867 World’s Fair, but he was not interested in giving up on the Salon jury. He wanted Paris to come to him and accept him—even if he had to endure their ridicule in the process.

Lack of Finish

Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Sisley had met through classes. Berthe Morisot was a friend of both Degas and Manet (she would marry Édouard Manet’s brother Eugène by the end of 1874). She had been accepted to the Salon, but her work had become more experimental since then. Degas invited Morisot to join their risky effort. The first exhibition did not repay the artists monetarily but it did draw the critics, some of whom decided their art was abominable. What they saw wasn’t finished in their eyes; these were mere “impressions.” This was not a compliment.

The paintings of Neoclassical and Romantic artists had a finished appearance. The Impressionists’ completed works looked like sketches, fast and preliminary “impressions” that artists would dash off to preserve an idea of what to paint more carefully at a later date. Normally, an artist’s “impressions” were not meant to be sold, but were meant to be aids for the memory—to take these ideas back to the studio for the masterpiece on canvas. The critics thought it was absurd to sell paintings that looked like slap-dash impressions and to present these paintings as finished works.

Landscape and Contemporary Life

Courbet, Manet and the Impressionists also challenged the Academy’s category codes. The Academy deemed that only “history painting” was great painting. These young Realists and Impressionists questioned the long established hierarchy of subject matter. They believed that landscapes and genres scenes (scenes of contemporary life) were worthy and important.

Light and Color

In their landscapes and genre scenes, the Impressionist tried to arrest a particular moment in time by pinpointing specific atmospheric conditions—light flickering on water, moving clouds, a burst of rain. Their technique tried to capture what they saw. They painted small commas of pure color one next to another.

When a viewer stood at a reasonable distance their eyes would see a mix of individual marks; colors that had blended optically. This method created more vibrant colors than colors mixed as physical paint on a palette.

An important aspect of the Impressionist painting was the appearance of quickly shifting light on the surface of forms and the representation changing atmospheric conditions. The Impressionists wanted to create an art that was modern by capturing the rapid pace of contemporary life and the fleeting conditions of light. They painted outdoors (en plein air) to capture the appearance of the light as it flickered and faded while they worked.

Reception

By the 1880s, the Impressionists accepted the name the critics gave them, though their reception in France did not improve quickly. Other artists, such as Mary Cassatt, recognized the value of the Impressionist movement and were invited to join. American and other non-French collectors purchased numerous works by the Impressionists. Today, a large share of Impressionist work remains outside French collections.

Videos

How to recognize Monet: The Basin at Argenteuil (4:02)

Monet, Rouen Cathedral Series (3:54)

Japonism[a], also called Japanism, is the study of Japanese art and artistic talent. Japonism affected fine arts, sculpture, architecture, performing arts and decorative arts throughout Western culture. The term is used particularly to refer to Japanese influence on European art, especially in impressionism.

Japonism was first described by French art critic and collector Philippe Burty in 1872.

Nineteenth Century Re-Opening

During the end of the Edo Period (1600–1854), after more than 200 years of seclusion, foreign merchant ships of various nationalities began to visit Japan. Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan ended a long period of national isolation and became open to imports from the West, including photography and printing techniques. With this new opening in trade, Japanese art and artifacts began to appear in small curiosity shops in Paris and London.

Japonism began as a craze for collecting Japanese art, particularly ukiyo-e. Some of the first samples of ukiyo-e were to be seen in Paris. In about 1856 the French artist Félix Bracquemond first came across a copy of the sketch book Hokusai Manga at the workshop of his printer, Auguste Delâtre. The sketchbook had arrived in Delâtre’s workshop shortly after Japanese ports had opened to the global economy in 1854; therefore, Japanese artwork had not yet gained popularity in the West. In the years following this discovery, there was an increase of interest in Japanese prints. They were sold in curiosity shops, tea warehouses, and larger shops. Shops such as La Porte Chinoise specialized in the sale of Japanese and Chinese imports. La Porte Chinoise, in particular, attracted artists James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas who drew inspiration from the prints.

Artists and Movements

Ukiyo-e was one of the main Japanese influences on Western art. Western artists were attracted to the colorful backgrounds, realistic interior and exterior scenes, and idealized figures. Emphasis was placed on diagonals, perspective, and asymmetry in ukiyo-e, all of which can be seen in the Western artists who adapted this style. It is necessary to study each artist as an individual who made unique innovations.

Edgar Degas and Japanese prints

In the 1860s, Edgar Degas began to collect Japanese prints from La Porte Chinoise and other small print shops in Paris. Degas’ contemporaries had begun to collect prints as well which gave him a large collection for inspiration. Among the prints shown to Degas was a copy of Hokusai’s Random Sketches which had been purchased by Bracquemond after seeing it in Delâtre’s workshop. The estimated date of Degas’ adoption of Japonism into his prints is 1875. The Japanese print style can be seen in Degas’ choice to divide individual scenes by placing barriers vertically, diagonally and horizontally. Similar to many Japanese artists, Degas’ prints focus on women and their daily routines. The atypical positioning of his female figures and the dedication to reality in Degas’ prints aligned him with Japanese printmakers such as Hokusai, Utamaro, and Sukenobu.

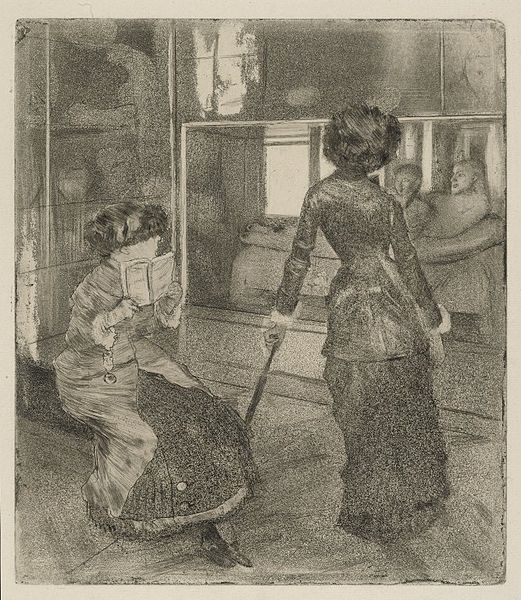

In Degas’ print Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery (1879-1880), the commonalities between Japanese prints and Degas’ work can be found in the two figures: one that stands and one that sits. The composition of the figures was familiar in Japanese prints. Degas also continues the use of lines to create depth and separate space within the scene. Degas’ most clear appropriation is of the woman leaning on a closed umbrella which is borrowed directly from Hokusai’s Random Sketches.

Japanese Gardens and Claude Monet

The impressionist painter Claude Monet modeled parts of his garden in Giverny after Japanese elements, such as the bridge over the lily pond, which he painted numerous times. By detailing just on a few select points such as the bridge or the lilies, he was influenced by traditional Japanese visual methods found in ukiyo-e prints, of which he had a large collection. He also planted a large number of native Japanese species to give it a more exotic feeling.

Vincent van Gogh and woodblock color palettes

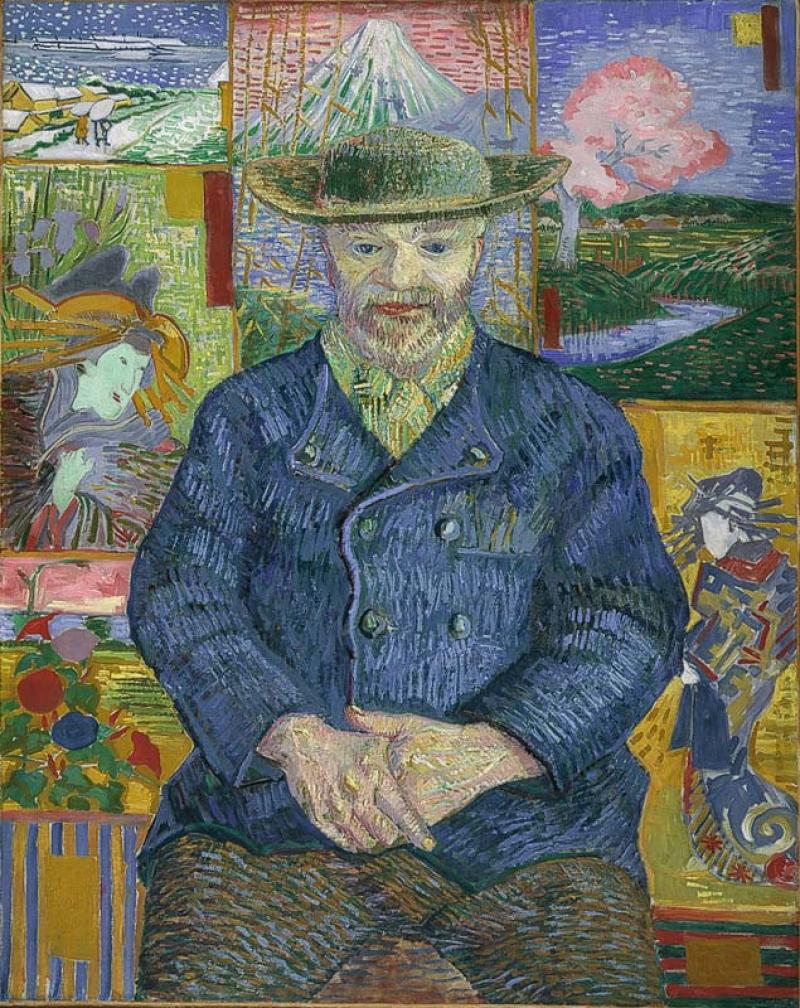

Portrait of Père Tanguy by Vincent van Gogh, an example of Ukiyo-e influence in Western art (1887) Vincent van Gogh began his deep interest in Japanese prints when he discovered illustrations by Félix Régamey featured in The Illustrated London News and Le Monde Illustré. Régamey created woodblock prints, followed Japanese techniques, and often depicted scenes of Japanese life. Van Gogh used Régamey as a reliable source for the artistic practices and everyday life scenes of the Japanese. Beginning in 1885, van Gogh switched from collecting magazine illustrations, such as Régamey, to collection ukiyo-e prints that could be bought in small Parisian shops. Van Gogh shared these prints with his contemporaries and organized a Japanese print exhibition in Paris in 1887. Van Gogh’s Portrait of Pere Tanguy (1887) is a portrait of his color merchant, Julien Tanguy. Van Gogh created two versions of this portrait, which both feature a backdrop of Japanese prints. Many of the prints behind Tanguy can be identified, with artists such as Hiroshige and Kunisada featured. Van Gogh filled the portrait with vibrant colors. He believed that buyers were no longer interested in grey-toned Dutch paintings, rather paintings with many colors were seen as modern and were sought after. He was inspired by Japanese woodblock prints and their colorful palettes. Van Gogh included into his own works the vibrancy of color in the foreground and the background of paintings that he observed in Japanese woodblock prints and made use of light to clarify.

James McNeill Whistler and British Japonism

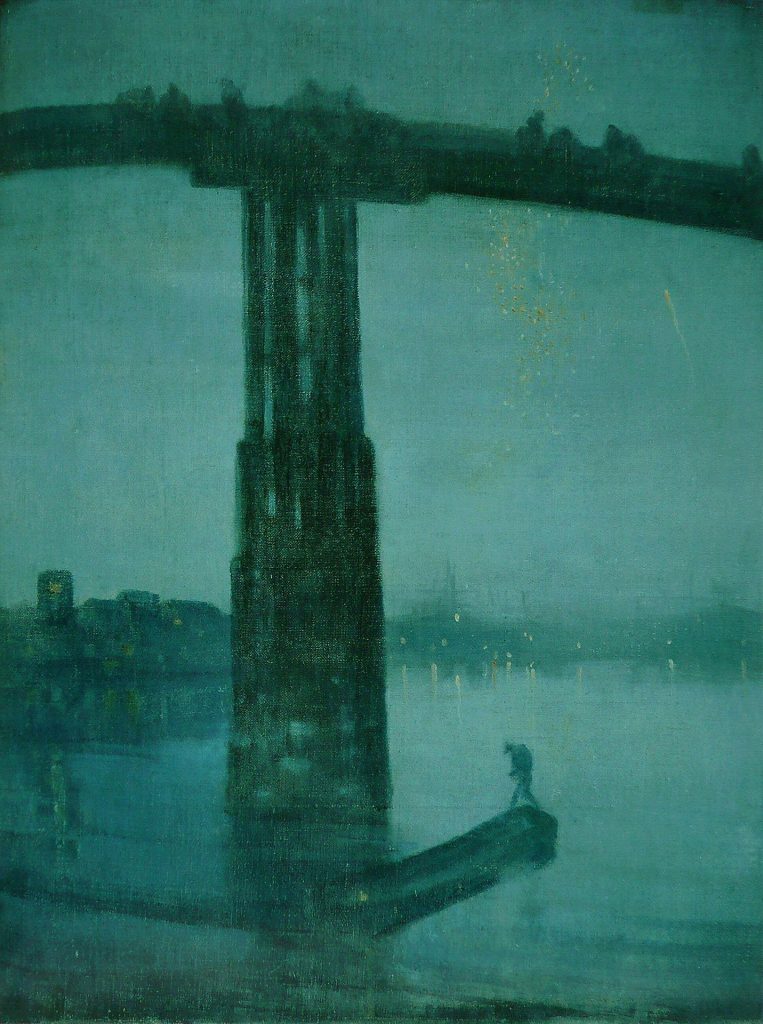

Japanese art was exhibited in Britain beginning in the early 1850s. These exhibitions featured a variation of Japanese objects, including maps, letters, textiles and objects from everyday life. These exhibitions served as a source of national pride for Britain and served to create a separate Japanese identity apart from the generalized “orient” cultural identity. James Abbott McNeill Whistler was an American artist who worked primarily in Britain. During the late 19th century, Whistler began to reject the Realist style of painting that his contemporaries favored. Instead, Whistler found simplicity and technicality in the Japanese aesthetic. Rather than copying specific Japanese artists and artworks, Whistler was influence by general Japanese methods of articulation and composition which he integrated into his works. Therefore, Whistler refrained from depicting Japanese objects in his paintings; instead, he used compositional aspects to infuse a sense of exoticism. Whistler’s Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge, displayed his interest in asymmetrical compositions and dramatic uses of foreshortening. This composition style would not be popular among his contemporaries for another ten years, however it was a characteristic of earlier Ukiyo-e art.

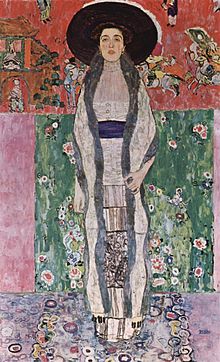

Gustav Klimt

The most well-known japonism painting of Gustav Klimt is The Second Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. Klimt was influenced by the Norwegian fauvist Edvard Munch in his later paintings.

Media Attributions

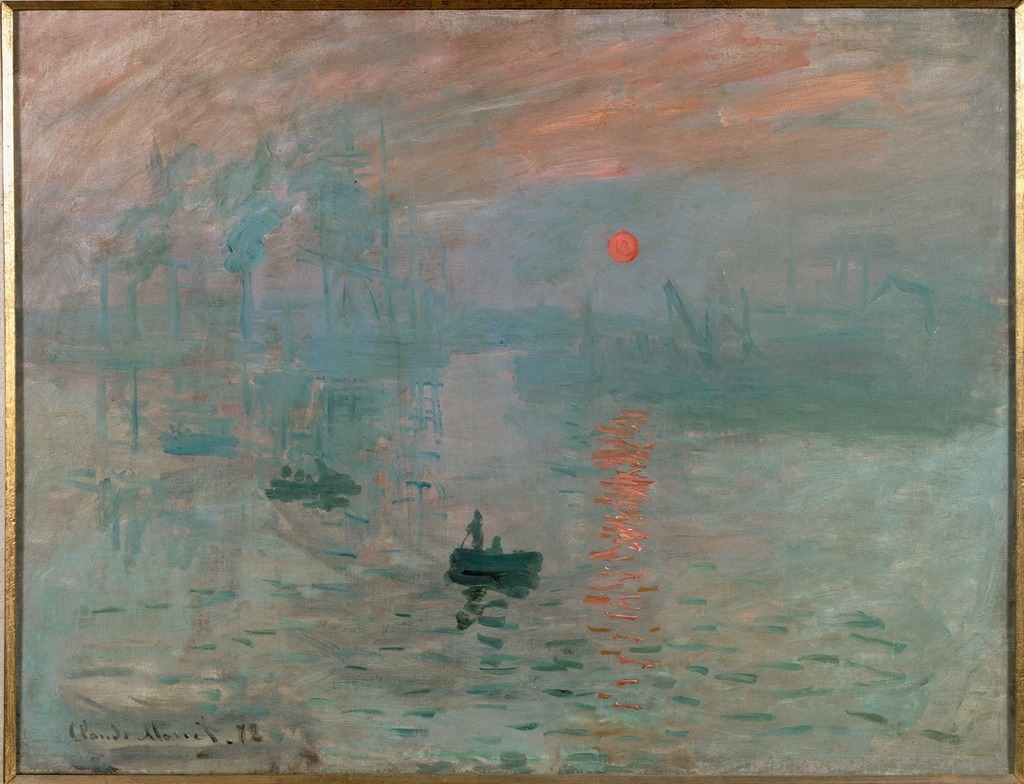

- Figure 1. Claude Monet, Impression Sunrise, 1872, oil on canvas. (Musée Marmottan, Paris; Image source: Erich Lessing/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via ArtStor. Used with permission. For educational use only)

- Figure 2. Edouard Manet, Dejeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), 1863, oil on canvas (Musée d’Orsay; Image source: Erich Lessing/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via ArtStor. Used with permission. For educational use only)

- Figure 3. Edgar Degas, Dance Class, 1873-1876, oil on canvas (Musée d’Orsay; Image source: Scala Archives via ArtStor. Used with permission. For educational use only)

- Figure 4. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Le moulin de la Galette, 1876, oil on canvas. (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; Image source: Art History Survey Collection via ArtStor. Used with permission. For educational use only)

- Figure 5. Berthe Morisot, Le Berceau (The Cradle), 1872, oil on canvas. (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; Image source: Erich Lessing/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via ArtStor. Used with permission. For educational use only)

- Figure 6. Claude Monet, Field of Poppies, 1873, oil on canvas. (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; Image source: Erich Lessing/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via ArtStor. Used with permission. For educational use only)

- Figure 7. Claude Monet, La Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877, oil on canvas. (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; Image source: Erich Lessing/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via ArtStor. Used with permission. For educational use only)

- Figure 8. Mary Cassatt, The Child’s Bath, 1893, oil on canvas. (Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, Inv. no. 1910.2; Image source: Scala Archives via ArtStor. Used with permission. For educational use only)

- Figure 9. Moon flask; possibly January 1868 or 1869; bone china; 26.4 × 20.6 × 10.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City; Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 10. Advertising poster for the comic opera The Mikado, which was set in Japan (1885) (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 11. Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery, 1879-1880. Aquatint, drypoint, soft-ground etching, and etching with burnishing, 26.8 x 23.6 cm (Image source: Metropolitan Museum of Art) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 12. Claude Monet, La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume), 1876 (Image source: Museum of Fine Arts Boston) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 13. Claude Monet, French – The Japanese Footbridge and the Water Lily Pool, Giverny (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 14. Portrait of Père Tanguy by Vincent van Gogh, an example of Ukiyo-e influence in Western art (1887) (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 15. Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 16. Gustav Klimt, The Second Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

Candela Citations

- Impressionism, an introduction. Authored by: Dr. Beth Gersh-Nesic. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/a-beginners-guide-to-impressionism/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- How to recognize Monet: The Basin at Argenteuil. Authored by: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/recognize-monet/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral Series. Authored by: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/monet-rouen-cathedral-series/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike