Chapter 11.15: Global Contemporary Art: 1980-Present

“Getting” Contemporary Art

It’s ironic that many people say they don’t “get” contemporary art because, unlike Egyptian tomb paintings or Greek sculptures, art made since 1960 reflects our own recent past. It speaks to the dramatic social, political, and technological changes of the last 50 years, and it questions many of society’s values and assumptions—a tendency of postmodernism, a concept sometimes used to describe contemporary art. What makes today’s art especially challenging is that, like the world around us, it has become more diverse and cannot be easily defined through a list of visual characteristics, artistic themes, or cultural concerns.

Minimalism and Pop Art, two major art movements of the early 1960s, offer clues to the different directions of art in the late 20th and 21st centuries. Both rejected established expectations about art’s aesthetic qualities and need for originality. Minimalist objects are spare geometric forms, often made from industrial processes and materials, which lack surface details, expressive markings, and any discernible meaning. Pop Art took its subject matter from low-brow sources like comic books and advertising. Like Minimalism, its use of commercial techniques eliminated emotional content implied by the artist’s individual approach, something that had been important to the previous generation of modern painters. The result was that both movements effectively blurred the line distinguishing fine art from more ordinary aspects of life, and forced us to reconsider art’s place and purpose in the world.

Shifting Strategies

Minimalism and Pop Art paved the way for later artists to explore questions about the conceptual nature of art, its form, its production, and its ability to communicate in different ways. In the late 1960s and 1970s, these ideas led to a “dematerialization of art” when artists turned away from painting and sculpture to experiment with new formats, including photography, film and video, performance art, large-scale installations, and earthworks. Although some critics of the time foretold “the death of painting,” art today encompasses a broad range of traditional and experimental media, including works that rely on Internet technology and other scientific innovations.

Contemporary artists continue to use a varied vocabulary of abstract and representational forms to convey their ideas. It is important to remember that the art of our time did not develop in a vacuum; rather, it reflects the social and political concerns of its cultural context. For example, artists like Judy Chicago, who were inspired by the feminist movement of the early 1970s, embraced imagery and art forms that had historical connections to women.

In the 1980s, artists appropriated the style and methods of mass media advertising to investigate issues of cultural authority and identity politics. More recently, artists like Maya Lin, who designed the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial Wall in Washington D.C., and Richard Serra, who was loosely associated with Minimalism in the 1960s, have adapted characteristics of Minimalist art to create new abstract sculptures that encourage more personal interaction and emotional response among viewers.

These shifting strategies to engage the viewer show how contemporary art’s significance exists beyond the object itself. Its meaning develops from cultural discourse, interpretation, and a range of individual understandings, in addition to the formal and conceptual problems that first motivated the artist. In this way, the art of our times may serve as a catalyst for an ongoing process of open discussion and intellectual inquiry about the world today.

The Pictures Generation

Appropriation—the strategy of selective borrowing—is a common theme in the history of modern art. Since the late nineteenth century, artists have both copied and imitated the work of other artists. Consider, for example, the work of Vincent Van Gogh, who copied the format and the compositions of Japanese color woodcuts (ukiyo-e). In the twentieth century, Pablo Picasso imitated the form of African masks for the faces of several female figures in his well-known painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon of 1907. The appropriation of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa by Marcel Duchamp in 1919 was a radical gesture, where Duchamp drew a handlebar mustache and goatee onto a postcard-size reproduction of Leonardo’s famous painting.

In the late 1970s, appropriation took on new significance. Artists later identified as belonging to the “Pictures Generation” moved beyond the use of appropriation as a formal strategy, and instead made appropriation the content of the works as well. Repositioning the forms and ideas from previous works of art, these artists were invested in creating new meanings in new contexts. Through the manipulation of media like film and photography in particular, these artists questioned both the possibility and the significance of “originality.”

Many of the artists now known as the “Pictures Generation” were so named mainly because of their inclusion in the 1977 exhibition “Pictures” at Artists Space in New York City. The five artists included in this exhibition—Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, and Philip Smith—explored the boundaries between reality and images, originals and reproductions. This concern with “pictures” expanded beyond those five original artists to include many others working in this period as well. In a retrospective exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2009 the work of artists Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Richard Prince, David Salle, Cindy Sherman, and Michael Zwack was included under the broad category of Pictures Generation art. Despite the diversity in the subjects and approaches of these artists, most did work in photography and film—two media particularly suited to the blurring of boundaries between originals and reproductions, and between the real world and the world of images. From the moment of its invention, photography inspired debates around the question of originality; with one negative image capable of producing an unknown number of positive prints, can we consider any of those as original?

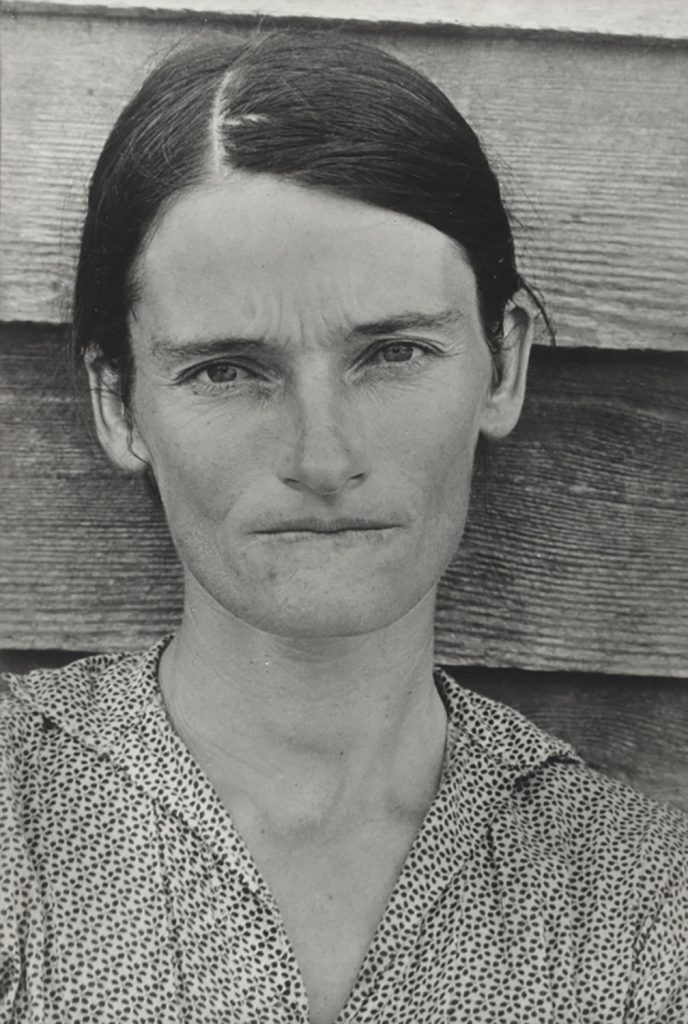

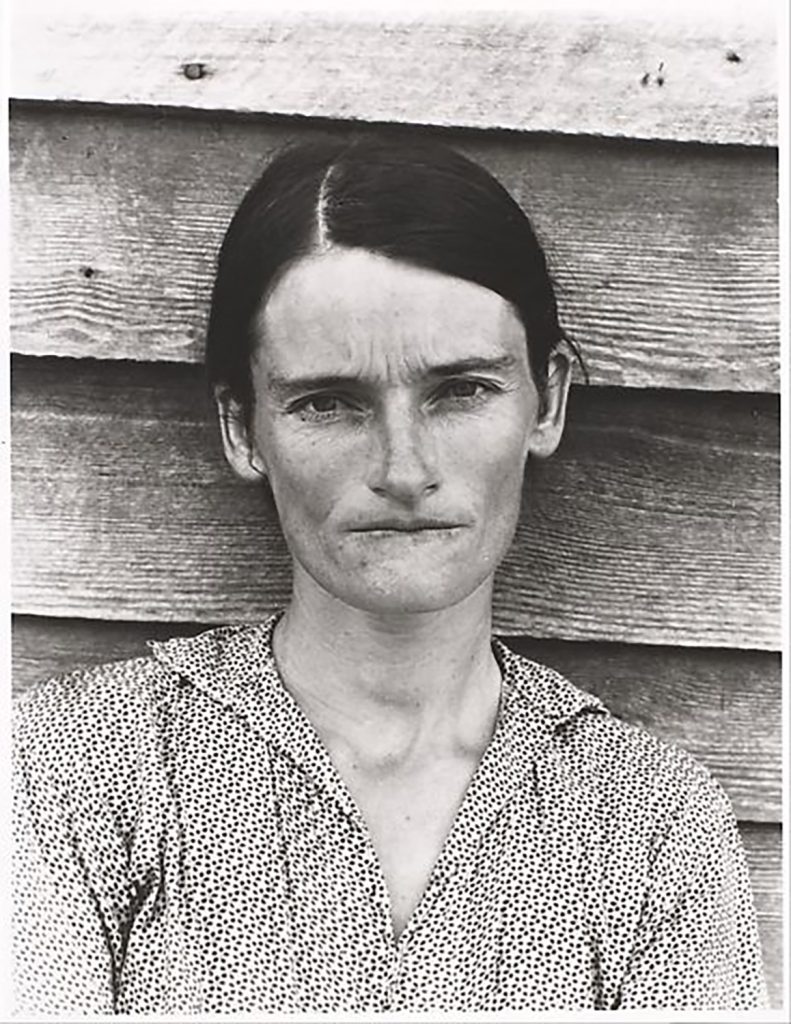

The work of Sherrie Levine, one of the artists included in the 1977 “Pictures” exhibition, engages with these questions of originality via her use of photography. For Levine’s After Walker Evans, 1981, for example, the artist rephotographed a 1936 black-and-white portrait by Walker Evans of the wife of an Alabama sharecropper. Although it may be difficult to distinguish the 1936 and 1981 photographs, it is important to note that Levine did not produce her image from Evans’ negative or even his gelatin silver print; rather, Levine’s After Walker Evans was taken from a catalog reproduction of Evans’ 1936 image. Levine’s specific appropriation of Evans’ reproduced image confronts the contradiction between photography (an infinitely reproducible medium) and fine art (which favors the unique object). In other words, Levine’s reproductions of photographic reproductions intervene directly in the debates surrounding the medium of photography—as a document or a work of art, as a unique image or an endlessly reproducible copy. When we look at Levine’s After Walker Evans, we are reminded of the words of the historian and critic Douglas Crimp, who curated the 1977 “Pictures” exhibition. “Underneath each picture,” Crimp wrote, “there is always another picture.”

Postmodernism

Artists directly engaged with appropriation in the 1970s were doing so under the influence of postmodernism. In previous generations, artists were praised for their ability to create new ideas and objects. Originality was the hallmark of modernism, and artists were presumed to be independent creators of objects and their meaning. However, by the late 1960s, such ideas were beginning to break down. New theories about the impossibility of originality developed in the field of literary theory began to permeate the art world. A key text of this period was a 1968 essay by French philosopher Roland Barthes entitled “Death of the Author.” Barthes realigned the focus of literary theory from the creation of language to its enunciation. This meant that the act of interpretation was more important than the act of creation. Artists were suddenly freed from the burden and the expectations of complete originality; what mattered now was how artists could interpret, reconfigure, and reposition already extant works and ideas to create other meanings. Levine’s After Walker Evans expresses these postmodern ideas. It can be difficult to locate the “original” in Levine’s image. Instead, the focus here is on how the artist uses the medium of photography to disrupt modernist lineages, which frequently put white, heterosexual males at the “origin” of these trajectories.

The “After” in her title refers to the existence of a prior model but underscores Levine’s break with it.

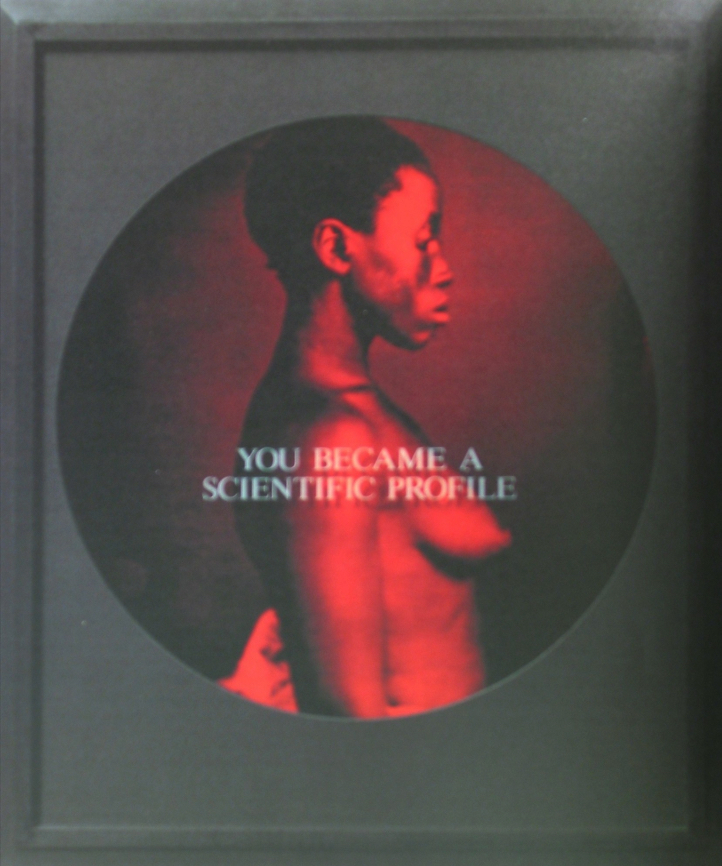

Artists have continued to explore strategies of appropriation. For example, in the early 1990s, the photographer Carrie Mae Weems appropriated daguerreotype photographs of slaves taken in 1850 by J.T. Zealy in her Sea Island Series. Like in the work of Levine, Weems’ use of these photographs was more than an appropriation of the image itself; the focus here is on reworking the meaning of these original photographs. The nineteenth-century daguerreotypes objectify the bodies of South Carolina slaves, reducing them to specimens in order to prove a theory about the innate inferiority of people of African descent. In her re-presentation of these nineteenth-century images, however, Weems transforms the sitters of the photographs from objects to people. Her tinting of the photographs and their installation alongside a narrative gives the subjects of these images a new voice of their own, acknowledging the history of oppression from which they came.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Andy Warhol, Large Campbell’s Soup Can. Silkscreen ink and silver paint on linen, 1964 (Image source: © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

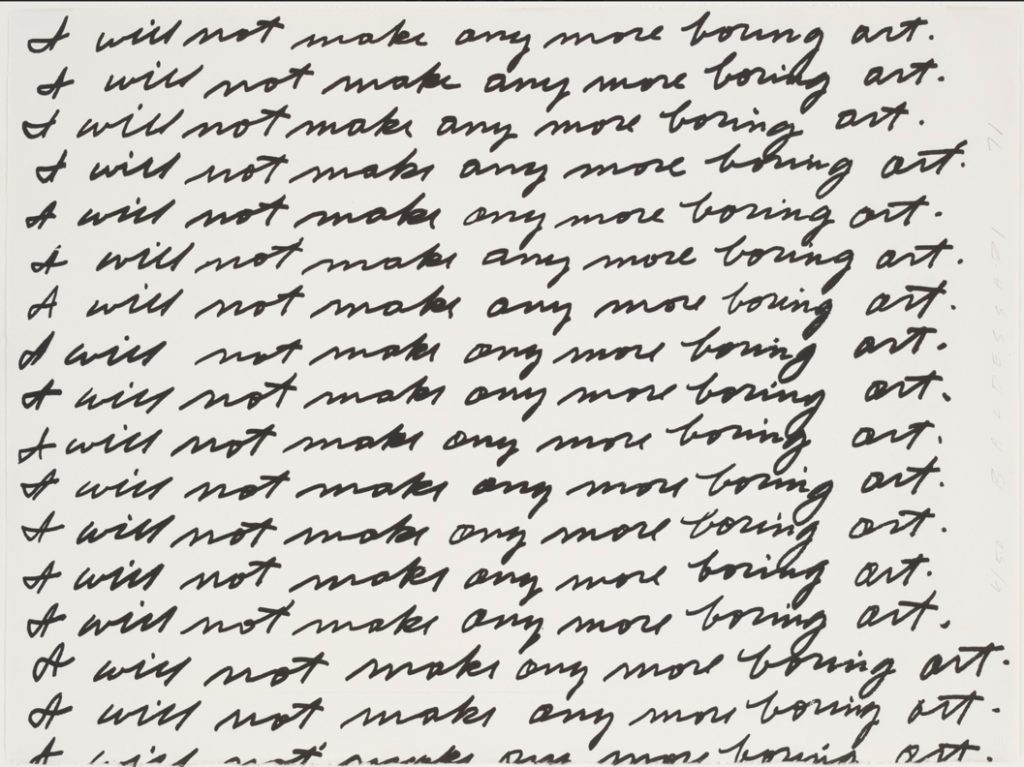

- Figure 2. John Baldessari. I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, Lithograph, 1971 (Image source: Museum of Modern Art. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 3. Walker Evans, Alabama Tenant Farmer Wife, 1936, gelatin silver print (Image source: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 4. Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans: 4, gelatin silver print (Image source: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 5. Carrie Mae Weems, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995 (Image source: Museum of Modern Art. Used with permission, for education use only)

Candela Citations

- Contemporary Art, An Introduction. Authored by: Dr. Virginia B. Spivey. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/contemporary-art-an-introduction-3/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike