Chapter 11.11: Postmodern Art, 1960-Present

Postmodernism can be seen as a reaction against the ideas and values of modernism, as well as a description of the period that followed modernism’s dominance in cultural theory and practice in the early and middle decades of the twentieth century. The term is associated with scepticism, irony and philosophical critiques of the concepts of universal truths and objective reality. ~Tate Modern Museum

Perhaps the greatest, and certainly the loudest, event in American cultural life since World War II was what the critic Irving Sandler has called “The Triumph of American Painting”—the emergence of a new form of art that allowed American painting to dominate the world. This dominance lasted for at least 40 years, from the birth of the so-called New York school, or Abstract Expressionism, around l945 until at least the mid-1980s, and it took in many different kinds of art and artists. – Encyclopedia Britannica

Performance Art

Performance art is a time-based art form that typically features a live presentation to an audience or to onlookers (as on a street) and draws on such arts as acting, poetry, music, dance, and painting. It is generally an event rather than an artifact, by nature ephemeral, though it is often recorded on video and by means of still photography.

When Art Intersects With Life

Many people associate performance art with highly publicized controversies over government funding of the arts, censorship, and standards of public decency. Indeed, at its worst, performance art can seem gratuitous, boring or just plain weird. But, at its best, it taps into our most basic shared instincts: our physical and psychological needs for food, shelter, sex, and human interaction; our individual fears and self-consciousness; our concerns about life, the future, and the world we live in. It often forces us to think about issues in a way that can be disturbing and uncomfortable, but it can also make us laugh by calling attention to the absurdities in life and the idiosyncrasies of human behavior.

Performance art differs from traditional theater in its rejection of a clear narrative, use of random or chance-based structures, and direct appeal to the audience. The art historian RoseLee Goldberg writes:

Historically, performance art has been a medium that challenges and violates borders between disciplines and genders, between private and public, and between everyday life and art, and that follows no rules.*

Although the term encompasses a broad range of artistic practices that involve bodily experience and live action, its radical connotations derive from this challenge to conventional social mores and artistic values of the past.

Historical Sources

While performance art is a relatively new area of art history, it has roots in experimental art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Echoing utopian ideas of the period’s avant-garde, these earliest examples found influences in theatrical and music performance, art, poetry, burlesque and other popular entertainment. Modern artists used live events to promote extremist beliefs, often through deliberate provocation and attempts to offend bourgeois tastes or expectations. In Italy, the anarchist group of Futurist artists insulted and hurled profanity at their middle-class audiences in hopes of inciting political action. Following World War II, performance emerged as a useful way for artists to explore philosophical and psychological questions about human existence. For this generation, who had witnessed destruction caused by the Holocaust and atomic bomb, the body offered a powerful medium to communicate shared physical and emotional experience. Whereas painting and sculpture relied on expressive form and content to convey meaning, performance art forced viewers to engage with a real person who could feel cold and hunger, fear and pain, excitement and embarrassment—just like them.

Videos

The Case for Performance Art | The Art Assignment | PBS Digital Studios (9:10)

The Case for Conceptual Art (11:27)

Conceptual Art

Conceptual art, called post-object art or art-as-idea, artwork whose medium is an idea (or a concept), is usually manipulated by the tools of language and sometimes documented by photography. Its concerns are idea-based rather than formal. Conceptual art is typically associated with a number of American artists of the 1960s and ’70s.

Conceptual art was first so named in 1961 by the American theorist and composer Henry Flynt and described in his essay Concept Art (1963).

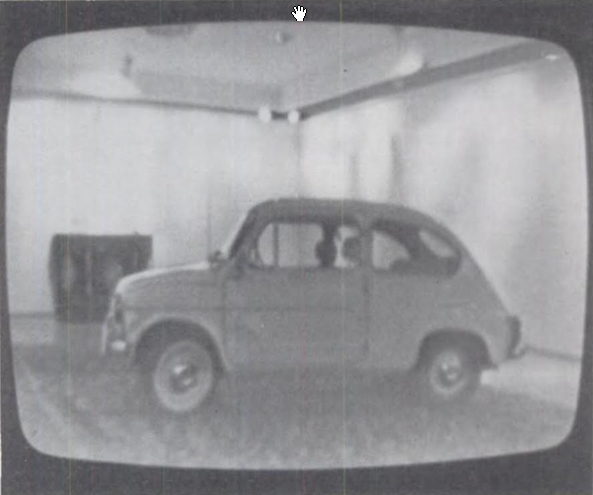

In 1972, the De Saisset Art Museum at Santa Clara University in the San Francisco Bay Area gave the artist Tom Marioni several hundred dollars to help cover expenses for mounting an exhibition of his work at the institution. Instead of using the money to purchase art materials, Marioni bought an older model used car, a Fiat 750, which he carefully maneuvered into the museum for the opening of his show. The vehicle, parked on top of an oriental rug, formed the centerpiece for this exhibition, titled My First Car. Was this really art, or was it a scam to get the museum to pay for a car the artist wanted? After learning about the show, the University President concluded that it was more of the latter and ordered the show closed. Presumably, he was put off by how My First Car profited Marioni without involving any technical skill or hard work on the part of the artist.

Not just a prank

Marioni’s work was in many ways typical of the late 1960s and early 1970s art practices that came to be known as Conceptual art. As the term suggests, Conceptual art placed emphasis upon the concept or idea, and deemphasized the actual physical manifestation of the work. Thus, an artist did not need manual skill to produce his work, and in fact could get away with not making anything at all. Rather than being a mere prank (as many dismissed it at the time), Marioni’s work was a proposal for a new kind of art that deliberately disavowed art’s traditional role as a showcase for the creative genius and technical abilities of the artist.

Marioni’s appropriation of a car is only one example of a number of very diverse art practices that are grouped under the term Conceptual art. Refusing to work in any one medium, and especially hostile to the painting and sculptural traditions in Western art, Conceptual artists would broaden their approach to art-making to include just about any material: text, photography, found objects, and even the physical space of the gallery, as long as there was a conceptual dimension that emphasized a set of principles or process involved in producing a given artwork, rather than a finished product.

Conceptual goes mainstream

Conceptual art had its precursors, notably early twentieth-century Dada artists like Marcel Duchamp, whose “readymades” (mass-produced objects like a urinal or bicycle wheel that he designated as artworks) also questioned the tenet that art be solely a demonstration of an artist’s creative and technical abilities. In the 1950s and early 1960s, movements such as Fluxus, Happenings, Neo-Dada, and Nouveau Réalisme also employed techniques we could categorize as Conceptual art from today’s vantage point. Embracing ephemeral and performative practices, and provoking viewers with sometimes aggressive assaults upon “good taste,” they, too, let go of the notion of art as refined object. In the decades following, Conceptual art strategies were taken up by feminist as well as postmodern artists, and today conceptualism has become a global phenomenon, with artists from around the world deploying video, photography, text, body art, performance, and installation, often interchangeably. Ironically, the strategies of Conceptual art, once a challenge to orthodox, mainstream modern art, have now become so fundamental that they are taken to be a given of contemporary art practice.

Land Art – Earthwork – Earth Art

The MoMA provides the following definition for Earthwork: Art that is made by shaping the land itself or by making forms in the land using natural materials like rocks or tree branches. Earthworks range from subtle, temporary interventions in the landscape to significant, sculptural, lasting alterations made with heavy earth-moving machinery. Some artists have also brought the land into galleries and museums, creating installations out of dirt, sand, and other materials taken from nature. Earthworks were part of the wider conceptual art movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Also called Land Art or Earth Art.

Video

The Case for Land Art | THE ART ASSIGNMENT | PBS Digital Studios (9:29)

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Roman Ondák, Measuring the Universe, 2007, shown enacted at MoMA, 2009. As visitors enter the room, they are invited to stand against the wall and have someone mark off their height and label it with their first name and the date of their visit. As the artist describes it: “Every visitor [who] enters my room is welcome to be measured. And participation of people is very spontaneous” (Image and text source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 2. Tom Marioni, My First Car, 1972, De Saisset Gallery, Santa Clara, California Image source: Performance Anthology (Image source: Book of California Performance Art, eds. Carl E. Loeffler Darlene Tong. Google Books. Used with permission, Last Gasp Publications)

- Figure 3. Mel Bochner, Measurement Room, 1969, tape and letraset, dimensions variable (Image source: The Museum of Modern Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

Candela Citations

- Performance Art: An Introduction. Authored by: Dr. Virginia B. Spivey. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/performance-art-an-introduction/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Conceptual Art: An Introduction. Authored by: Dr. Tom Folland and Dr. Leta Y. Ming. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/conceptual-art-introduction/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Postmodernism. Retrieved from: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/postmodernism. Project: Art Term. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Used with permission, for educational use only

- Earthwork. Provided by: MoMA. Retrieved from: https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/earthwork. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Used with permission, for educational use only