Chapter 10.4: The Renaissance in Northern Europe

Traditional accounts of the Renaissance favor a narrative that places the birth of the Renaissance in Florence, Italy. In this narrative, Italian art and ideas migrate North from Italy (largely because of the travels of the great German artist Albrecht Dϋrer who studied, admired, and was inspired by Italy, and he carried his Italian experiences back to Germany).

However, so much changed in northern Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that the era deserves to be evaluated on its own terms. So we use the term “Northern Renaissance” to refer to the Renaissance that occurred in Europe north of the Alps. Some of the most important changes in northern Europe include the:

- invention of the printing press, c. 1450

- advent of mechanically reproducible media such as woodcuts and engravings

- formation of a merchant class of art patrons that purchased works in oil on panel

- international trade in urban centers

In Italy, the Renaissance was deeply influenced by the art and culture of Ancient Greece and Rome—in part because the art and architecture of antiquity was more immediately available (ruins were plentiful in many cities). Northern Europe however did not have such ready access to ancient monuments and so tended to draw instead more directly from medieval traditions such as manuscript illuminations.

During the 15th and 16th centuries, the Low Countries became a political and artistic center focused around the cities of Bruges and Ghent. Because Flemish masters employed a workshop system, wherein craftsmen helped to complete their art, they were able to mass produce high-end panels for sale throughout Europe. The Flemish School emerged almost concurrently with the Italian Renaissance. However, while the Italian Renaissance was based on the rediscoveries of classical Greek and Roman culture, the Flemish school drew influence from the area’s Gothic past. These artists also experimented with oil paint earlier than their Italian Renaissance peers. Using thin layers of paint, called glazes, northern artists created a depth of color that was entirely new, and because oil paint can imitate textures far better than fresco or tempera, it was perfectly suited to representing the material reality that was so important to Renaissance artists and their patrons. In the Northern Renaissance, we see artists making the most of oil paint—creating the illusion of light reflecting on metal surfaces or jewels, and textures that appear like real fur, hair, wool or wood.

The great artists of this period created work that reflected their increasingly mercantile world, even when they worked for the court of the Dukes. The spiritual world reigned supreme but the representation of wealth and power were also a hugely important motive for patrons whether a pope, a duke, or a banker.

Before 1450, Renaissance humanism had little influence outside Italy; however, after 1450 these ideas began to spread across Europe. This influenced the Renaissance periods in Germany, France, England, the Netherlands, and Poland.

The Flemish School

The Flemish School, which has also been called the Northern Renaissance, the Flemish Primitive School, and Early Netherlandish, refers to artists who were active in Flanders during the 15th and 16th centuries, especially in the cities of Bruges and Ghent. The three most prominent painters during this period—Jan van Eyck, Robert Campin, and Rogier van der Weyden—were known for making significant advances in illusionism, or the realistic and precise representation of people, space, and objects. The preferred subject matter of the Flemish School was typically religious in nature, but small portraits were common as well. The majority of this work was presented as either panels, single altarpieces, or more complex altarpieces, which were usually in the form of diptychs or polyptychs.

Robert Campin

Robert Campin, considered the first master of the Flemish School, has been identified with the signature “Master of Flemalle,” which appears on numerous works of art. Campin is known for producing highly realistic works, for making great use of perspective and shading, and for being one of the first artists to work with oil paint instead of tempera . One of his best known works, the Merode Altarpiece, is a triptych that depicts an Annunciation Scene. The Archangel Gabriel approaches Mary as she is reading in a room that is recognized as a typical middle class Flanders home. The work is highly realistic, and the objects throughout the painting conveyed recognizable, religious meaning to viewers at the time.

Jan Van Eyck

Jan van Eyck, a contemporary of Campin, is widely considered to be one of the most significant Northern European painters of the 15th century. He is known for signing and dating his work “ALS IK KAN” (“AS I CAN”). Signatures were not particularly customary during this time, but helped to secure his lasting reputation. Active in Bruges and very popular within his own lifetime, van Eyck’s work was highly innovative and technical. It exhibited a masterful manipulation of oil paint and a high degree of realism. While van Eyck completed many famous paintings, perhaps his most famous is the Ghent Altarpiece, a commissioned polyptych from around 1432.

Another important work is Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Double Portrait (1434) which shows a well-to-do couple in a tasteful, bourgeois interior. The text in the back of the image identifies the date and Jan van Eyck as the artist. Art historians disagree about what is actually happening in the image, whether this is a betrothal or a marriage, or perhaps something else entirely. One of the most important aspects of this painting is the symbolic meanings of the objects, as we saw earlier in our course. This painting is a touchstone for the study of iconography, a method of interpreting works of art by deciphering symbolic meaning.

Though Jan van Eyck did not invent oil paint, he used the medium to greater effect than any other artist to date. Oil would become a predominant medium for painting for centuries, favored in art academies into the nineteenth century and beyond. The Arnolfinis counted as middle class because their wealth came from trade rather than inherited titles and land. The power of the merchant-class patrons of northern Europe cultivated a taste for art made for domestic display.

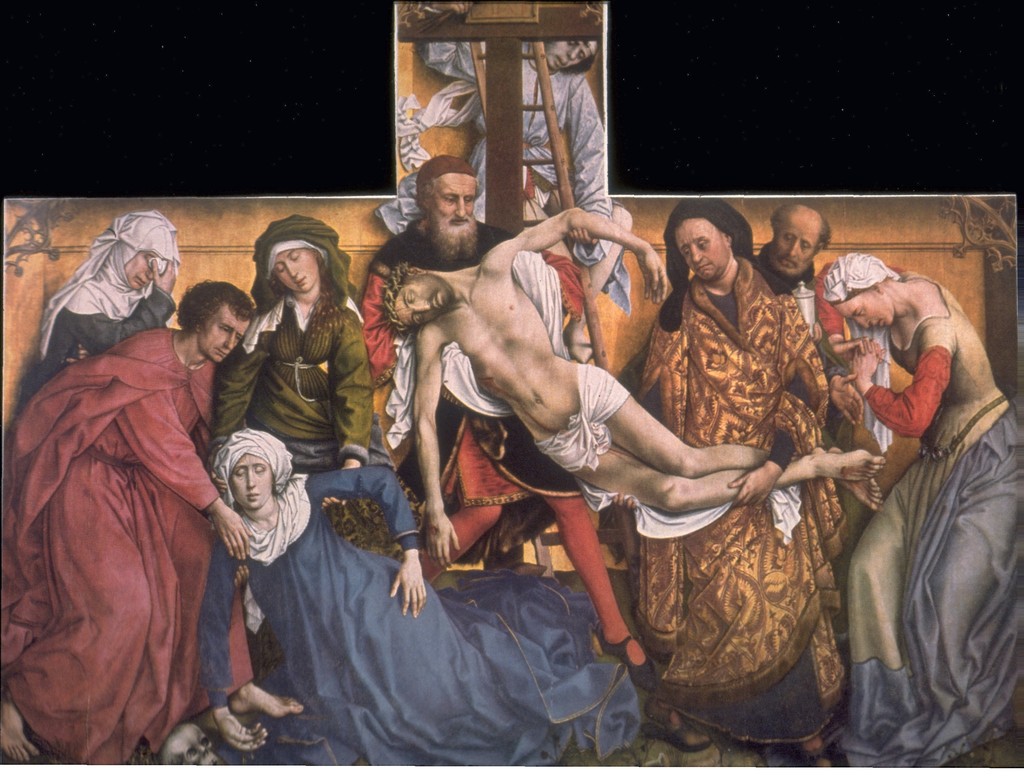

Rogier van der Weyden

Rogier van der Weyden is the last of the three most renowned Early Flemish painters. An apprentice under Robert Campin, van der Weyden exhibited many stylistic similarities, including the use of realism. Highly successful in his lifetime, his surviving works are mainly religious triptychs, altarpieces, and commissioned portraits. By the end of the 15th century, van der Weyden surpassed even van Eyck in popularity. Van der Weyden’s most well-known painting is The Descent From the Cross, circa 1435.

Van der Weyden, Deposition (7 minutes)

German Painting in the Northern Renaissance

The German Renaissance is reflective of Italian and German influence in its paintings, and one is not present without the other.

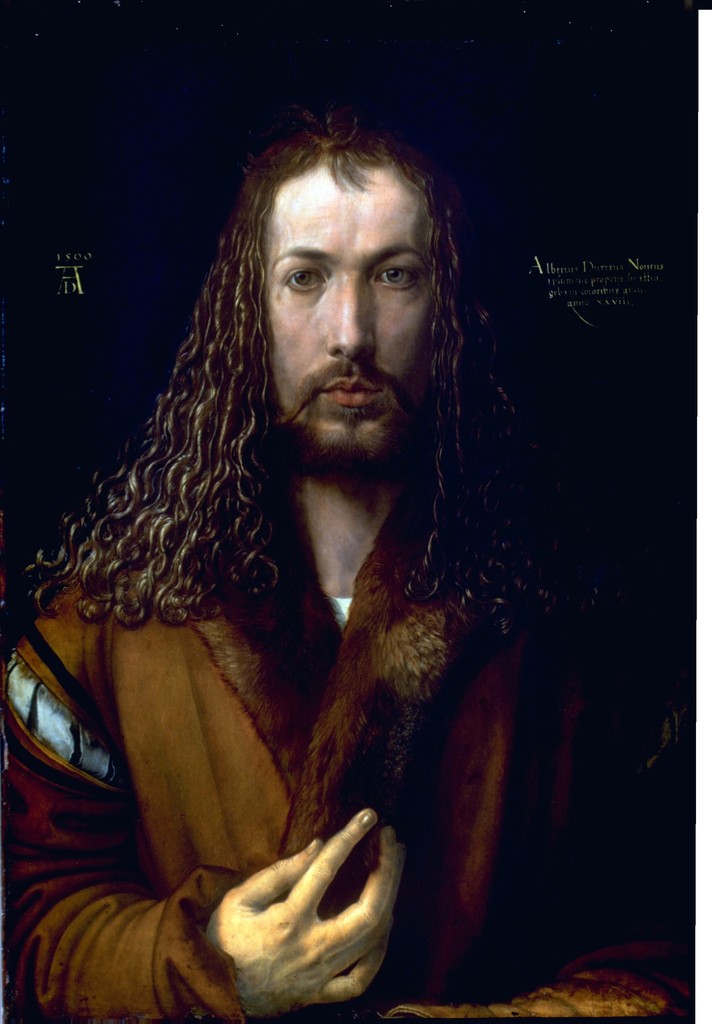

Albrecht Dürer

One of a small number of Germans with the means to travel internationally, Nuremberg born Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) helped bring the artistic styles of the Renaissance north of the Italian Alps after his visits to the Italian peninsula in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Like the Italian artists Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarotti, Dürer was a Renaissance Man, adept in multiple disciplines such as painting, printmaking, and mathematical theorizing. Dürer’s introduction of classical motifs into Northern art has secured his reputation as one of the most important figures of the Northern Renaissance. This is reinforced by his theoretical treatises, which involve principles of mathematics, perspective, and ideal proportions.

One of Dürer’s paintings that display a clearly classical rendering of the body is Adam and Eve (1507), the first full-scale nude subjects in German painting. A clear departure from flat and stylized representations of the Romanesque and Gothic periods, the bodies appear naturalistic and dynamic, with each figure posed in an engaging contrapposto pose. Although they stand against a black background, the ground on which both figures stand and the tree that flanks Eve comprise naturalistic landscape elements. Likely the first landscape painter in Early Modern Europe, Dürer honed his landscape painting skills working en plein air at home and during his travels.

Matthias Grünewald

Lying somewhat outside these developments is Matthias Grünewald, whose birthplace is located in eastern France and who left very few works. However, his Isenheim Altarpiece (1512–1516), produced in collaboration with Niclaus of Haguenau, has been widely regarded as the greatest German Renaissance painting since it was restored to critical attention in the 19th century. It is an intensely emotional work that continues the German Gothic tradition of unrestrained gesture and expression, using Renaissance compositional principles while maintaining the Gothic format of the multi-winged polyptych.

In its closed form, the Isenheim Altarpiece depicts an emaciated Christ whose skin bears many dark spots. Its lower panel, which houses relief sculptures displayed on certain feast days, opens in a manner that makes the legs of Christ, being entombed, appear amputated. Not surprisingly, Grünewald produced the altarpiece for a chapel in an infirmary that treated patients with a variety of diseases, including ergotism, and isolated remaining strains of the plague. A primary symptom of both diseases was painful sores on the skin. In some cases of ergotism, limbs developed gangrene and had to be amputated. Through the skin sores and seemingly amputated legs, Grünewald informs the viewer that Christ understands and feels the suffering of the sick. Such “humanization” of Biblical figures became common throughout Europe during the Renaissance in an effort to make them more relatable to worshippers.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait, 1500 (Alte Pinakothek, Munich; Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives via Artstor; Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 2. The Merode Altarpiece attributed to Robert Campin: The Merode Altarpiece is a triptych that features the Archangel Gabriel approaching Mary, who is reading in a well-decorated, typical middle-class Flanders home (Image source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 3. Jan Van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece, 1432, oil on panel. (Sint Baafskathedraal Gent [Saint Bavo Cathedral]; Image source: Erich Lesson Culture and Fine Arts Archives via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 4. Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, oil on oak. (The National Gallery, London Bought, 1842). This work is a portrait of Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini (left) and his wife (right), but is not intended as a record of their wedding. His wife is not pregnant, as is often thought, but holding up her full-skirted dress in the contemporary fashion (Image source: The National Gallery of London via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 5. Rogier van der Weyden, Descent from the Cross, 1435, tempera/oil on wood (Prado, Madrid; Image source: Art History Survey Collection via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 6. Albrecht Durer, Adam and Eve, 1507, oil on wood. (Museo del Prado; Image source: University of California, San Diego via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 7. Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece (closed): Oil on panel (exterior). Wooden relief sculptures (interior). 1512–16 (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, Alsace; Image source: © 2006, SCALA, Florence / ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

Candela Citations

- An introduction to the Northern Renaissance in the fifteenth century. Authored by: Dr. Bonnie Noble. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/an-introduction-to-the-northern-renaissance-in-the-fifteenth-century/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike