Chapter 10.3: The Italian Renaissance: Cinquecento – The High Renaissance

When most people think of the Renaissance, the names that come to mind are of the artists from the period known as the High Renaissance: Leonardo and Michelangelo, for instance. This is a period of brilliant artists and big, ambitious projects.

Michelangelo: Sculptor, Painter, Architect, and Poet

Michelangelo was known as “il divino,” (in English, “the divine one”) and it is easy for us to see why. So much of what he created seems to us to be super-human.

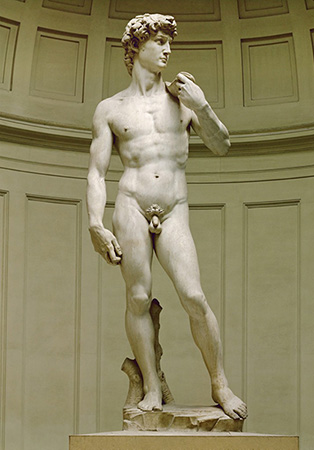

When Michelangelo was in his late 20s, he sculpted the 17-foot tall David. This colossus seemed to his contemporaries to rival or even surpass ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. David—and his later sculptures such as Moses and the Slaves—demonstrated Michelangelo’s astounding ability to make marble seem like living flesh and blood. So much so, it is difficult to imagine that these were created with a hammer and chisel. In painting, if we look at the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, with its elegant nudes and powerful seated figures, and the now-iconic image of the Creation of Adam, Michelangelo set a new standard for painting the human figure, one in which the body was not just an actor in a narrative, but emotionally and spiritually expressive on its own. And then there is his architecture, where Michelangelo reordered ancient forms in an entirely new and dramatic ways. It is no wonder then too, that Vasari, who knew Michelangelo, would write about how Michelangelo excelled in all three arts: painting, sculpture and architecture.

The Pieta Sculpture

The Pietà was a popular subject among northern European artists. It means Pity or Compassion and represents Mary sorrowfully contemplating the dead body of her son, which she holds on her lap. This sculpture was commissioned by a French Cardinal living in Rome.

Look closely and see how Michelangelo made marble seem like flesh, and look at those complicated folds of drapery. It is important here to remember how sculpture is made. It was a messy, rather loud process (which is one of the reasons that Leonardo claimed that painting was superior to sculpture!). Just like painters often mixed their own paint, Michelangelo forged many of his own tools and often participated in the quarrying of his marble — a dangerous job.

When we look at the extraordinary representation of the human body here, we remember that Michelangelo, like Leonardo before him, had dissected cadavers to understand how the body worked.

The David Sculpture

Michelangelo’s David stands nearly 17 feet tall. Remember that the biblical figure of David was special to the citizens of Florence—he symbolized the liberty and freedom of their republican ideals, which were threatened at various points in the fifteenth century by the Medici family and others. Watch a video about the importance of the figure of David for Florence.

Visiting the Chapel

The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is one of Michelangelo’s most famous works.

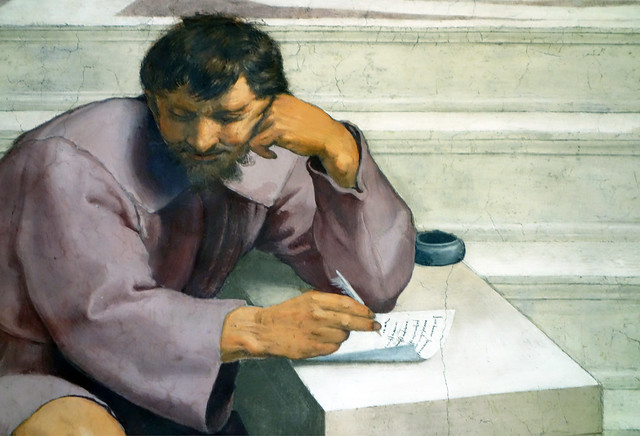

It is no wonder that Raphael, struck by the genius of the Sistine Chapel, rushed back to his School of Athens in the Vatican Stanze and inserted Michelangelo’s weighty, monumental likeness sitting at the bottom of the steps of the school.

Images and Videos

Michaelangelo, Pietà (3:38)

David (marble statue) (5:40)

Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (6:47)

Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, born on April 6, 1483 in Urbio, Italy, was a highly accomplished painter, printmaker and architect of the High Renaissance period. Though he lived only 37 years he was a master artist with a unique style that incorporated a strong humanistic style prominent during this period. Alongside Michelangelo and Leonardo, Raphael was considered one of the three most important artists of the High Renaissance period. The School of Athens, a fresco painted between 1509 – 1511, is one of his most famous paintings. It presents all the greatest mathematicians, philosophers and scientists from classical antiquity gathered together sharing their ideas and learning from each other. These figures all lived at different times, but here they are gathered together under one roof. The picture has long been seen as “Raphael’s masterpiece and the perfect embodiment of the classical spirit of the Renaissance”.

Image and Video

Raphael School of Athens (10:42)

Titian

Titian, Italian in full Tiziano Vecellio was one of the greatest Italian Renaissance painter of the Venetian School. He was recognized early in his own lifetime as a supremely great painter, and his reputation has in the intervening centuries never suffered a decline. In 1590 the art theorist Giovanni Lomazzo declared him “the sun amidst small stars not only among the Italians but all the painters of the world.”

The universality of Titian’s genius is not questioned today. In his portraits he searched and penetrated human character and recorded it in canvases of pictorial brilliance. His religious compositions cover the full range of emotion from the charm of his youthful Madonnas to the tragic depths of the late Crucifixion and the Entombment. In his mythological pictures he captured the gaiety and abandon of the pagan world of antiquity, and in his paintings of the nude Venus (Venus and Adonis) and the Danae (Danae with Nursemaid) he set a standard for physical beauty and often sumptuous eroticism that has never been surpassed.

Image and Video

Titian: ‘Bacchus and Ariadne’ | Paintings | The National Gallery, London (2:50)

Giorgione

“Giorgione, also called Giorgio da Castelfranco, was another extremely influential Italian painter who was one of the initiators of a High Renaissance style in Venetian art. His qualities of mood and mystery were epitomized in The Tempest (c. 1505), an evocative pastoral scene, which was among the first of its genre in Venetian painting.

In portraiture, Giorgione made a most profound and far-reaching impression. Venetian painters such as Titian, Palma Vecchio, and Lorenzo Lotto so closely imitated him in the early 16th century that it is at times virtually impossible to distinguish between them. The Tempest is a milestone in

Renaissance landscape painting, with its dramatization of a storm about to break. Here is the kind of poetic interpretation of nature that the Renaissance writers Pietro Bembo and Jacopo Sannazzaro evoked. This feeling for nature is probably also intimately related to, though not directly derived from, the philosophical “naturalism” of the contemporary Venetian and Paduan humanists grouped around the important Renaissance philosopher Pietro Pomponazzi.” (Encyclopaedia Britannica)

Image and Video

Giorgione, The Tempest (5:55)

How to Recognize Italian Renaissance Art

A brief introduction to Italian Renaissance art, that will help you recognize its prominent characteristics. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker.Created by Beth Harris and Steven Zucker.

How to Recognize Italian Renaissance Art (10:10)

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Michelangelo, Dying Slave, 1513-1515, marble. (Louvre; Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 2. Michelangelo, Rebellious Slave, 1513-1515, marble. (Louvre; Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 3. Michelangelo, Pieta, 1498-1500, marble. (Basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano; Image source: © 2006, SCALA, Florence / ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 4. Michelangelo, David, 1501-1504, marble. (Galleria dell’Accademia (Florence, Italy; Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 5. Interior, Sistine Chapel, the Vatican, Rome, Lazio, Italy (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, Roy Rainford / Robert Harding World Imagery / Universal Images Group. Rights Managed / For Education Use Only).

- Figure 6. Heraclitus, whose features are based on Michelangelo’s and his seated pose is based on the prophets and sibyls from Michelangelo’s frescoes on the Sistine Chapel Ceiling (detail), Raphael, School of Athens, 1509-11, Stanza della Segnatura (Vatican City, Rome; Image source: Steven Zucker via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7. Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1520, oil on canvas. (The National Gallery, London Bought, 1826; Image source: The Cleveland Museum of Art via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 8. Giorgione, The Tempest, 1510, oil on canvas. (Accademia, Venice; Image source: Art History Survey Collection via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

Candela Citations

- Toward the High Renaissance, An Introduction. Authored by: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/toward-the-high-renaissance-an-introduction/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike