Chapter 10.2: The Italian Renaissance: The Quattrocento – Renaissance in the 1400s

The Renaissance really gets going in the early years of the 15th century in Florence. In this period, which we call the Quattrocento or Early Renaissance, Florence is not a city in the unified country of Italy, as it is now. Instead, Italy was divided into many city-states (Florence, Milan, Venice etc.), each with its own government (some were ruled by despots, and others were republics).

The Florentine Republic We normally think of a Republic as a government where everyone votes for representatives who will represent their interests to the government (think of the United States pledge of allegiance: “and to the republic for which it stands…”). However, Florence was a Republic in the sense that there was a constitution that limited the power of the nobility (as well as laborers) and ensured that no one person or group could have complete political control (so it was far from our ideal of everyone voting, in fact, a very small percentage of the population had the vote). Political power resided in the hands of middle-class merchants, a few wealthy families (such as the Medici, important art patrons who would later rule Florence), and the powerful guilds.

One of the reasons why the Renaissance begins in Florence is because of the extraordinary wealth accumulated in Florence during this period among a growing middle and upper class of merchants and bankers. The people of Renaissance Florence, like most city–states of the era, were composed of four social classes: the nobles, the merchants, the tradesmen and the unskilled workers. The nobles lived on large estates outside the city walls. They owned most of the city’s land, so the nobles controlled. The nobles served as military officers, royal advisers and as politicians. The nobles were disdainful of the merchant class, who gained wealth in industries like wool processing, shipbuilding and banking.

The merchants sought to protect their wealth by controlling the government and marrying into noble families. They became patrons of great artists in order to gain public favor. Because of this patronage, the arts flourished in Florence.

Florence also saw itself as the ideal city-state, a place where the freedom of the individual was guaranteed and where many citizens had the right to participate in the government -very different than living in the Duchy of Milan, for example, which was ruled by a succession of Dukes with absolute power.

The Beginning

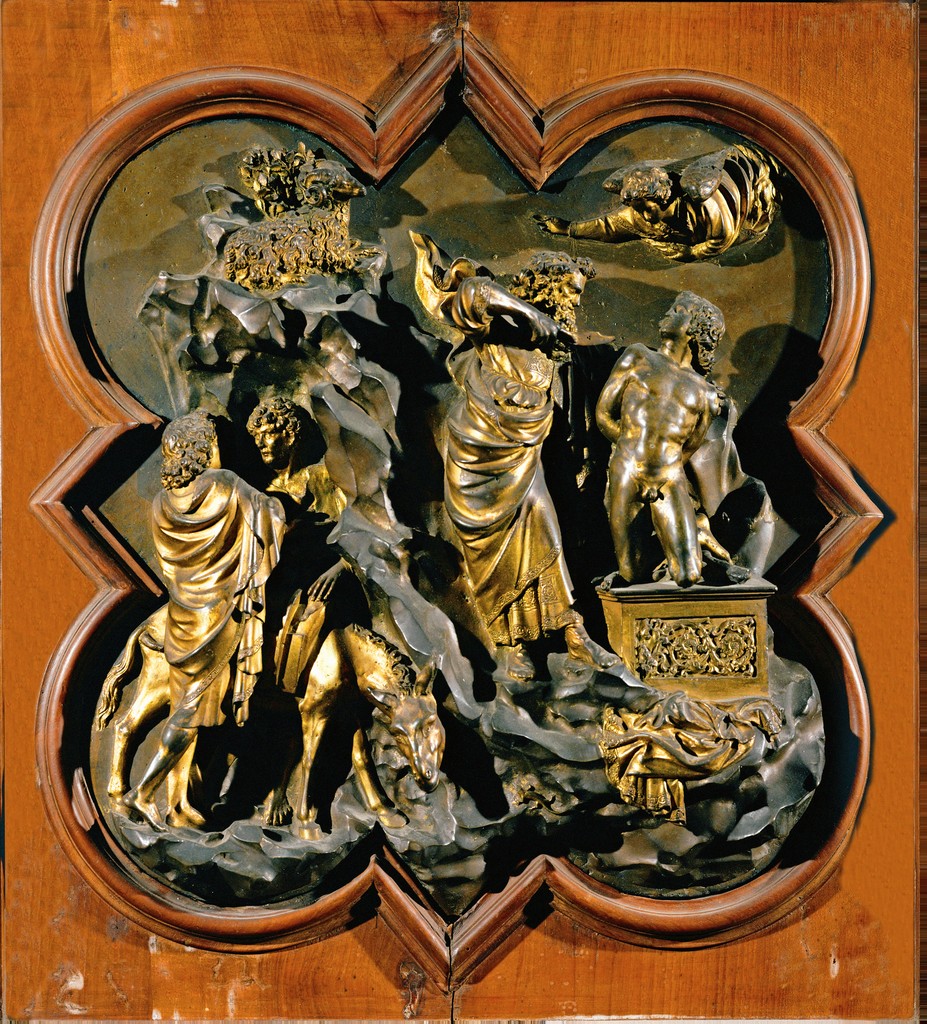

Most art historians mark the beginning of the Renaissance by the competition for the commission to make a pair of bronze doors for the Baptistery of the Cathedral of Florence. Artists were given the task of representing the biblical scene of Abraham’s sacrifice of his son Isaac in a bronze relief of quatrefoil shape. The entry panels of Ghiberti and of Filippo Brunelleschi -the well-known architect of the dome of the Cathedral of Florence, are the sole survivors of the contest. Ghiberti’s panels displayed a graceful and lively composition executed with a mastery of the goldsmith’s art. In 1402 Ghiberti was chosen to make the doors by a large panel of judges; their decision brought immediate and lasting recognition and prominence to the young artist.

The next artist and works of note was a student under the workshop of Ghiberti. The full power of Donatello first appeared in two marble statues, St. Mark and St. George (both completed c. 1415), for niches on the exterior of Orsanmichele, the church of Florentine guilds. Here, for the first time since Classical antiquity and in striking contrast to medieval art, the human body is rendered as a self-activating functional organism, and the human personality is shown with a confidence in its own worth.

Images and Videos

Brunelleschi & Ghiberti, the Sacrifice of Isaac (5:24)

Orsanmichele and Donatello’s St. Mark (4:52)

Masaccio

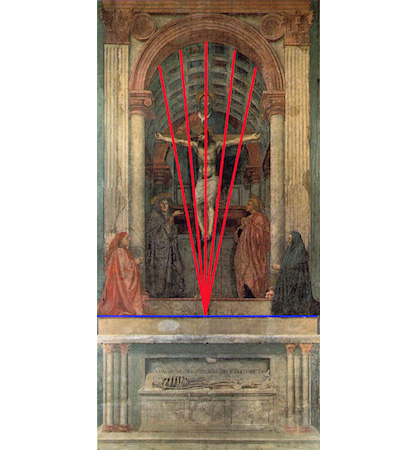

Masaccio was the first painter in the Renaissance to incorporate Brunelleschi’s discovery, linear perspective, in his art. He did this in his fresco the Holy Trinity, in Santa Maria Novella, in Florence.Have a close look at the painting and at this perspective diagram below. The orthogonals can be seen in the edges of the coffers in the ceiling (look for diagonal lines that appear to recede into the distance). Because Masaccio painted from a low viewpoint, as though we were looking up at Christ, we see the orthogonals in the ceiling, and if we traced all of the orthogonals, we would see that the vanishing point is on the ledge that the donors kneel on.

God is standing in this painting. This may not strike you all that much when you first think about it because our idea of God, our picture of God in our mind’s eye—as an old man with a beard—is very much based on Renaissance images of God. So, here Masaccio imagines God as a man. Not a force or a power, or something abstract, but as a man. A man who stands—his feet are foreshortened, and he weighs something and is capable of walking. In medieval art, God was often represented by a hand, as though God was an abstract force or power in our lives—but here he seems so much like a flesh and blood man. This is a good indication of Humanism in the Renaissance.

Masaccio’s contemporaries were struck by the palpable realism of this fresco, as was Vasari who lived over one hundred years later. Vasari wrote that “the most beautiful thing, apart from the figures, is a barrel-shaped vaulting, drawn in perspective and divided into squares filled with rosettes, which are foreshortened and made to diminish so well that the wall appears to be pierced.”¹

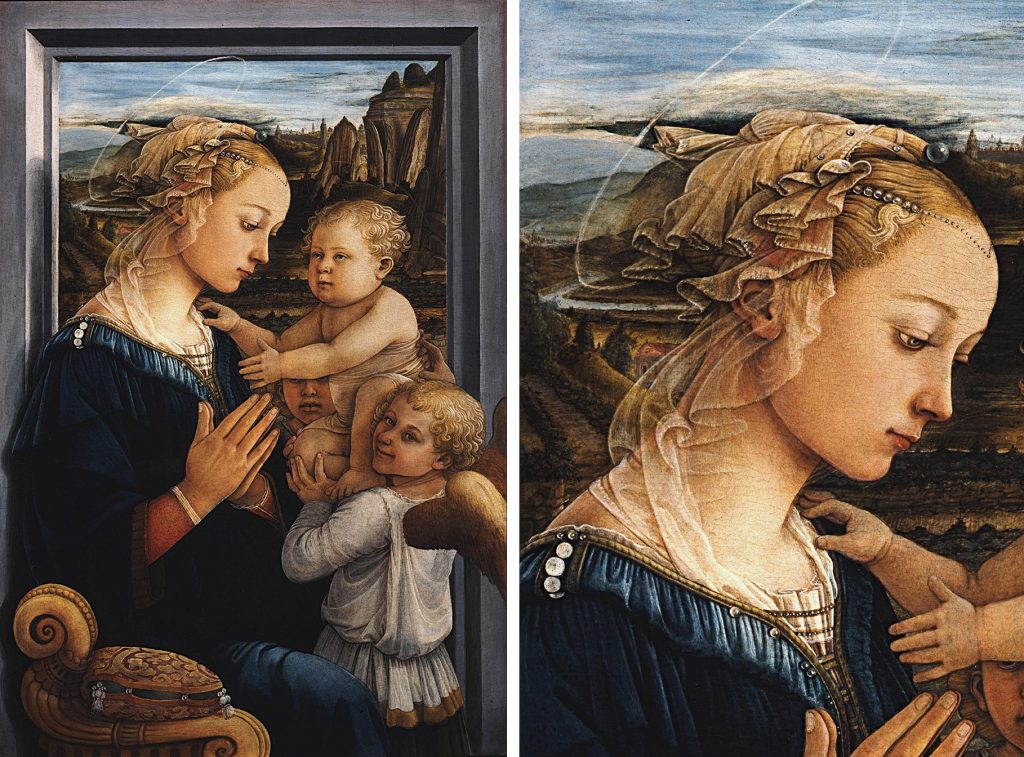

In the painting above, Madonna and Child with Two Angels by Fra Filippo Lippi halos virtually disappear.

Mary’s hands are clasped in prayer, and both she and the Christ child appear lost in thought, but otherwise the figures have become so human that we almost feel as though we are looking at a portrait. The angels look especially playful, and the one in the foreground seems like he might giggle as he looks out at us.

The delicate swirls of transparent fabric that move around Mary’s face and shoulders are a new decorative element that Lippi brings to Early Renaissance painting—something that will be important to his student, Botticelli. However, the modeling of Mary’s form—from the bulk and solidity of her body to the careful folds of drapery around her lap—reveal Masaccio’s influence. Lippi’s painterly style, which was formed in the early Florentine Renaissance, was fundamental to his pupil Sandro Botticelli. Lippi taught Botticelli the techniques of panel painting and fresco and gave him an assured control of linear perspective. Stylistically, Botticelli acquired from Lippi a repertory of types and compositions, a certain graceful fancifulness in costuming, a linear sense of form, and a partiality to certain paler hues that is still visible even after Botticelli had developed his own strong and resonant color schemes.

Botticelli

Botticelli has been called one of the greatest painters of the Florentine Renaissance. His The Birth of Venus and Primavera are often said to epitomize for modern viewers the spirit of the Renaissance.

Images and Videos

A celebration of beauty and love: Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (4:55)

Botticelli, Primavera (4:47)

Andrea Mantegna

In the Quattrocento, Andrea Mantegna is the first fully Renaissance artist of northern Italy. His best known surviving work is the Camera degli Sposi (“Room of the Bride and Groom”), or Camera Picta (“Painted Room”) (1474), in the Palazzo Ducale of Mantua, for which he developed a self-consistent illusion of a total environment. Almost 50 years after Masaccio uses Linear Perspective for the first time in a painting, Mantegna paints a whole room using Perspective to create spatial illusions in the eye of the viewer. His keen interest for foreshortening and odd angles in his compositions sets him apart from all other Renaissance Masters.

Videos

Mantegna, Camera degli Sposi (6:30)

Mantegna, Dead Christ (4:41)

About Leonardo

Towards the end of the Renaissance we will see the coming of age of one of the most famous artists to come out of this period in history: Leonardo Da Vinci.

The heavens often rain down the richest gifts on human beings, but sometimes they bestow with lavish abundance upon a single individual beauty, grace and ability, so that whatever he does, every action is so divine that he distances all other men, and clearly displays how his greatness is a gift of God and not an acquirement of human art. Men saw this in Leonardo. ~Vasari, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

Leonardo was born illegitimate to a peasant girl and a local Tuscan notary. He may have traveled from Vinci to Florence, where his father worked for several powerful families, including the Medici. At age seventeen, Leonardo reportedly apprenticed with the Florentine artist Verrocchio. Here, Leonardo gained an appreciation for the achievements of Giotto and Masaccio, and in 1472, he joined the artists’ guild, Compagnia di San Luca.

Because of his family’s ties, Leonardo benefited when Lorenzo de’ Medici (the Magnificent) ruled Florence. By 1478, Leonardo was completely independent of Verrocchio and may have then met the exiled Ludovico Sforza, the future Duke of Milan (Ludovico ruled as regent from 1481-94 before becoming Duke). In 1482, Leonardo arrived in Milan bearing a silver lyre (which he may have been able to play), a gift for Ludovico Sforza from the Florentine ruler, Lorenzo the Magnificent. Ludovico sought to transform Milan into a center of humanist learning to rival Florence.

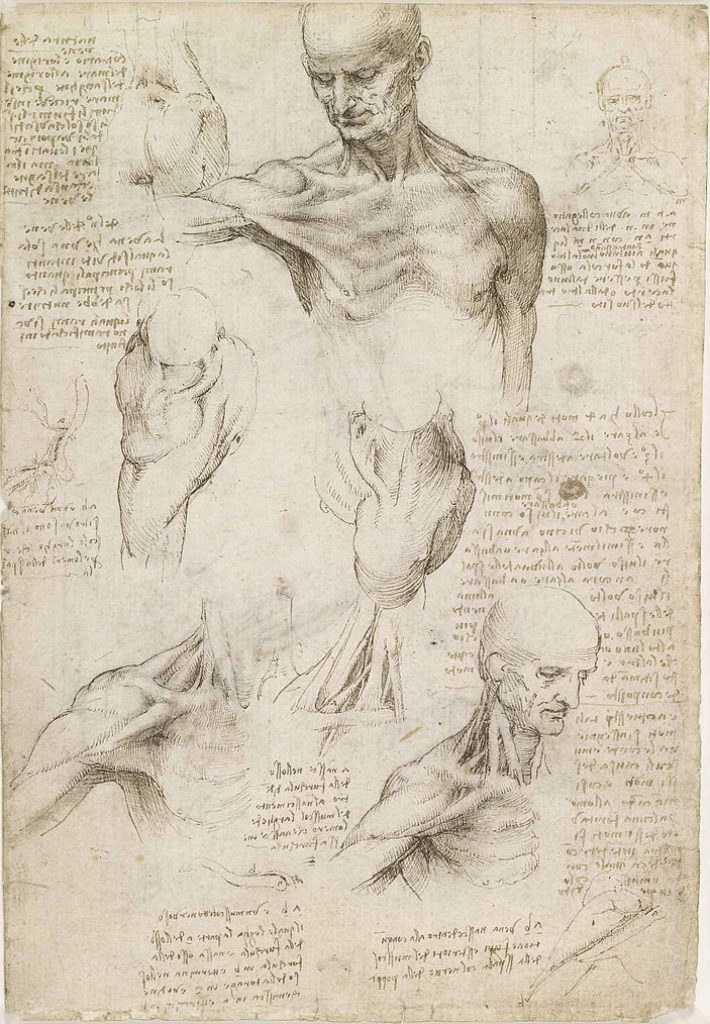

Leonardo flourished in this intellectual environment. He opened a studio, received numerous commissions, instructed students, and began to systematically record his scientific and artistic investigations in a series of notebooks. The archetypal “renaissance man,” Leonardo was an unrivaled painter, an accomplished architect, an engineer, a cartographer, and a scientist (he was particularly interested in biology and physics). Joining the practical and the theoretical, Leonardo designed numerous mechanical devices for battle, including a submarine, and even experimented with designs for flight.

In 1489, Leonardo secured a long-awaited contract with Ludovico and was honored with the title “The Florentine Apelles,” a reference to an ancient Greek painter revered for his great naturalism. Leonardo returned to Florence when Ludovico was deposed by the French King, Charles VII. While there, Leonardo would meet Niccolò Machiavelli, author of The Prince, and his future patron, François I (who ruled France from 1515-47). In 1516, after numerous invitations, Leonardo traveled to France and joined the royal court.

The Changing Role of the Artist

Artists in the Early Renaissance insisted that they should be considered intellectuals because they worked with their minds as well as with their hands. They defended this position by pointing to the scientific tools that they used to make their work more naturalistic—the study of human anatomy, mathematics and geometry, and linear perspective. These were clearly all intellectual pursuits. Leonardo is the best example of the changing status of the artist—Leonardo, who spent the last years of his life in France working for King Francis I, was often visited by the King (remember that the artist was considered only a skilled artisan in the Middle Ages and for much of the Early Renaissance). In the High Renaissance, we will find that artists are considered intellectuals and that they keep company with the highest levels of society. All of this has to do with Humanism in the Renaissance of course, and the growing recognition of the achievement of great individuals.

Image and Video

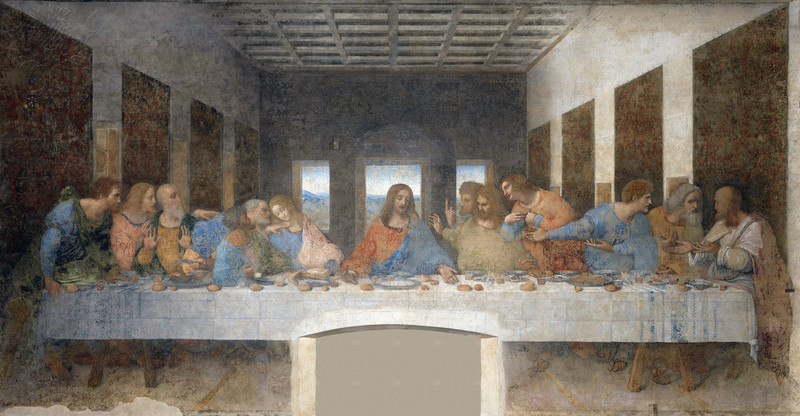

The Last Supper (7:40)

We live in a culture that is so saturated with images that it may be difficult to imagine a time when only the wealthiest people had their likeness captured. The wealthy merchants of Renaissance Florence could commission a portrait, but even they would likely only have a single portrait painted during their lifetime. A portrait was about more than likeness, it spoke to status and position. In addition, portraits generally took a long time to paint, and the subject would commonly have to sit for hours or days, while the artist captured their likeness.

The Mona Lisa was originally this type of portrait, but over time, its meaning has shifted, and it has become an icon of the Renaissance—perhaps the most recognized painting in the world. The Mona Lisa is likely a portrait of the wife of a Florentine merchant. For some reason, however, the portrait was never delivered to its patron, and Leonardo kept it with him when he went to work for Francis I, the King of France. The Mona Lisa is an extraordinary painting; so much so that the small portrait of a bourgeois Florentine woman has been the subject of many myths and conspiracy theories. But Leonardo da Vinci expert Martin Kemp is keen to emphasise the very ordinary circumstances of the portrait’s commission and the sitter’s life.

Video

The Mona Lisa: Painting beyond Portraiture | HENI Talks (8:46)

A Recent Discovery

An important copy of the Mona Lisa was recently discovered in the collection of the Prado in Madrid. The background had been painted over, but when the painting was cleaned, scientific analysis revealed that the copy was likely painted by another artist who sat beside Leonardo and copied his work, brush-stroke by brush-stroke. The copy gives us an idea of what the Mona Lisa might look like if layers of yellowed varnish were removed.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Map of Italy in 1494 (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 2. Donatello, Florentine, 1386-1466. St. George Tabernacle (originally for the OrSanMichelle, Florence) ca. 1415-1417, marble. (Bargello, Florence; Image source: Art History Survey Collection via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 3. Ghiberti, Sacrifice of Isaac, bronze relief partly gilded, 1401 (Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy; Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 4. Donatello, Florentine, 1386-1466. St. Mark [replica figure in situ, south facade of the Orsanmichele, Florence; original ca. 1411-1413] marble. (Florence, Tuscany, Italy; Image source: Art History Survey Collection via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 5. Perspective diagram of Holy Trinity, Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, Fresco, 667 x 317 cm, (Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy; Image source: Smarthistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 6. Left: Masaccio, Holy Trinity. Fresco, 1427. Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, The Granger Collection / Universal Images Group Rights. Managed / For Education Use Only. Right: Perspective diagram of Holy Trinity by Masaccio (Image source: Smarthistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7. Fra. Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child (left) Detail of Madonna and Child (right). Tempura on panel, c.1460-1465 (Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 8. Sandro Botticelli (1444-1510), Birth of Venus. Tempura on canvas, 1485. Galleria degli Uffizi, Floence, Italy (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, Bridgeman Art Library / Universal Images Group. Rights Managed / For Education Use Only).

- Figure 9. Sandro Boticelli, La Primavera. Tempura on wood, 1481. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, Alinari Archives / Universal Images Group. Rights Managed / For Education Use Only).

- Figure 10. Decoration of the Camera degli Sposi (Camera Picta) Created by Mantegna Andrea – Lacunars ceiling vault decorated with busts of Roman emperors and the oculus open on a cloudy sky, ringed with female figures and flying putti looking down – Italy, Mantua, Ducal Palace (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, Mondadori Electa / Learning Pictures / Universal Images Group. Rights Managed / For Education Use Only).

- Figure 10. Decoration of the Camera degli Sposi (Camera Picta) Created by Mantegna Andrea – Lacunars ceiling vault decorated with busts of Roman emperors and the oculus open on a cloudy sky, ringed with female figures and flying putti looking down – Italy, Mantua, Ducal Palace (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, Mondadori Electa / Learning Pictures / Universal Images Group. Rights Managed / For Education Use Only).

- Figure 12. Leonardo da Vinci, Study for the Head of Leda, 1506-1508, facsimile. (Gabinetto disegni e stampe degli Uffizi; Image source: (c) 2006, SCALA, Florence / ART RESOURCE, N.Y via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 13. Leonardo da Vinci, Superficial anatomy of the shoulder and neck, c. 1510, pen and ink over black chalk, 29.2 x 19.8 cm (Image source: Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 14. Leonardo da Vinci, Last Supper, mural, tempera and oil on plaster, 1498. Milan, Italy (Image source: Britannica ImageQuest, Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group. Rights Managed / For Educational Use Only).

- Figure 15. Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, c. 1503-05, oil on panel 30-1/4 x 21″ (Image source: Musée du Louvre via Wikimedia Commons. Used by permission, for education use only).

- Figure 16. Left: Unknown, Mona Lisa, c. 1503-05, oil on panel (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid); right: Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, c. 1503-05, oil on panel 30-1/4 x 21″ (Musée du Louvre; Image source: Smarthistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license