Chapter 6.3: Sculpture

Sculpture is defined as a three-dimensional (3D) art object made from the manipulation of materials that occupy space and have height, width, and depth. We categorize all sculpture into either an additive process, in which material is built up to create form, or a subtractive process, where material is removed from an existing mass, such as a chunk of stone, wood, or clay. There are four main methods used in producing sculpture, and all 3D art uses one or a combination of these four methods: carving, modeling, casting, or constructing. Below are definitions and examples for each method.

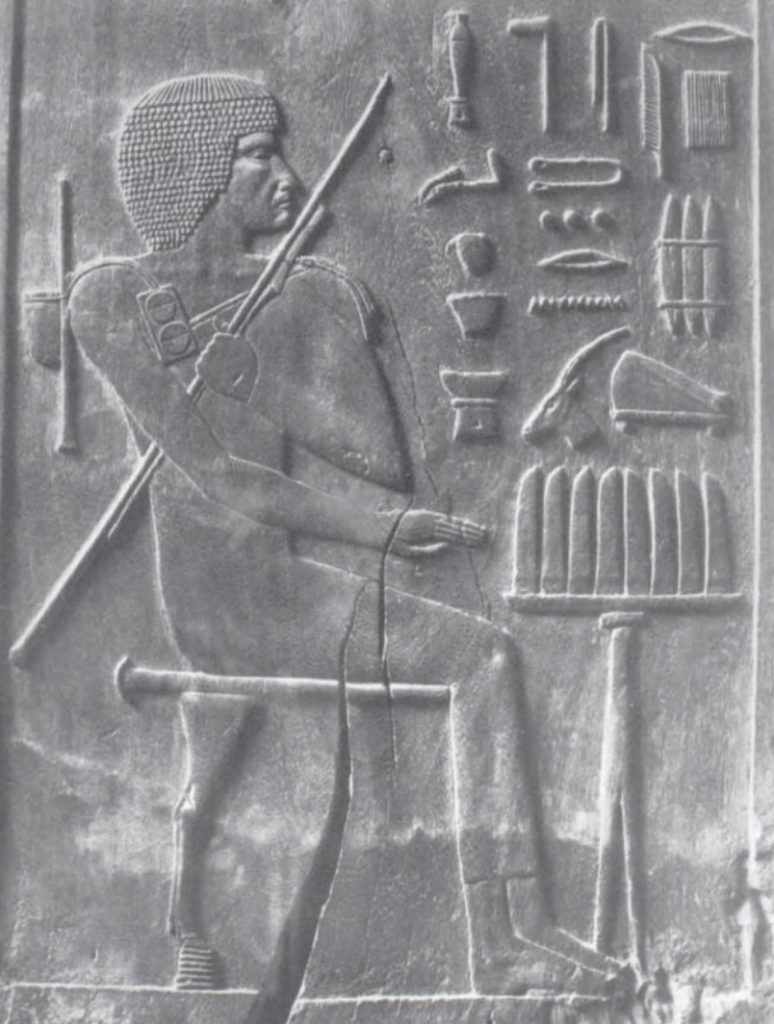

Sculpture can be either freestanding—“in the round”—or it can be relief—sculpture that projects from a background surface. There are two categories of relief sculpture: low relief and high relief. In low relief, the amount of projection from the background surface is limited. A good example of low relief sculpture would be coins, such as these ancient Roman types dating from c. 300 BCE to c. 400 CE (Figure 1). Also, much Egyptian wall art is low relief (Figure 2). High relief sculpture is when more than half of the sculpted form projects from the background surface. This method generally creates an effect called undercut, in which some of the projected surface is separate from the background surface. Mythological scenes depicted on the Parthenon, an ancient Greek temple (Figure 3), and the Corporate Wars series (Corporate Wars, Robert Longo) by Robert Longo (b. 1953, USA) are both examples of high relief using undercut.

Carving

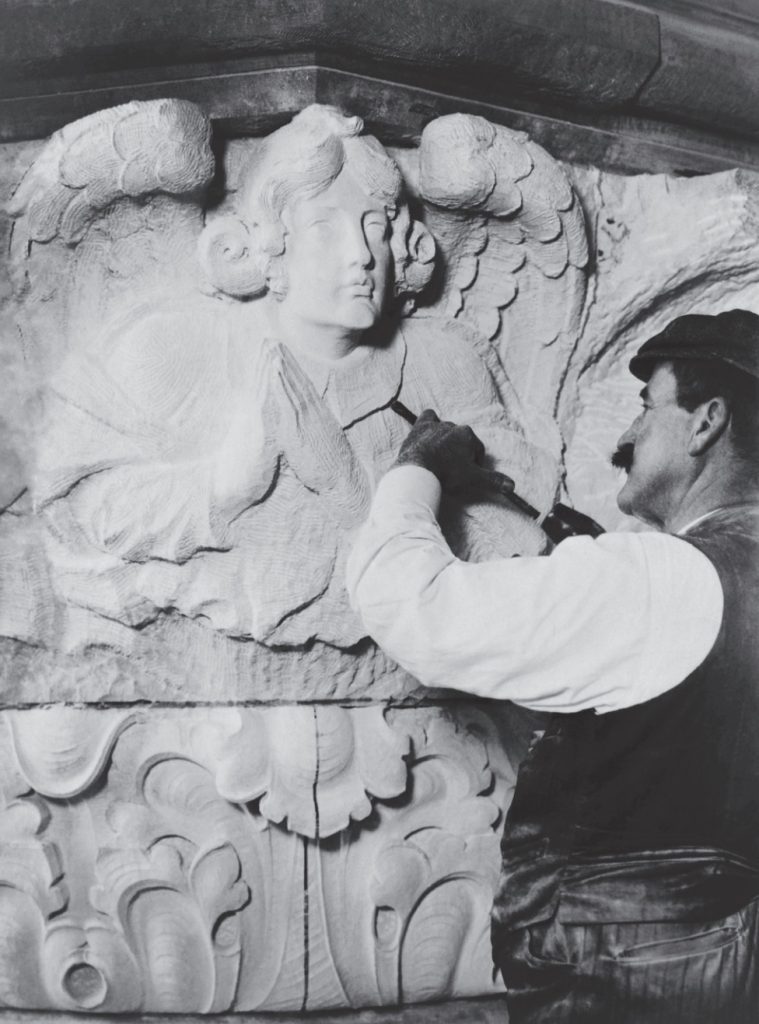

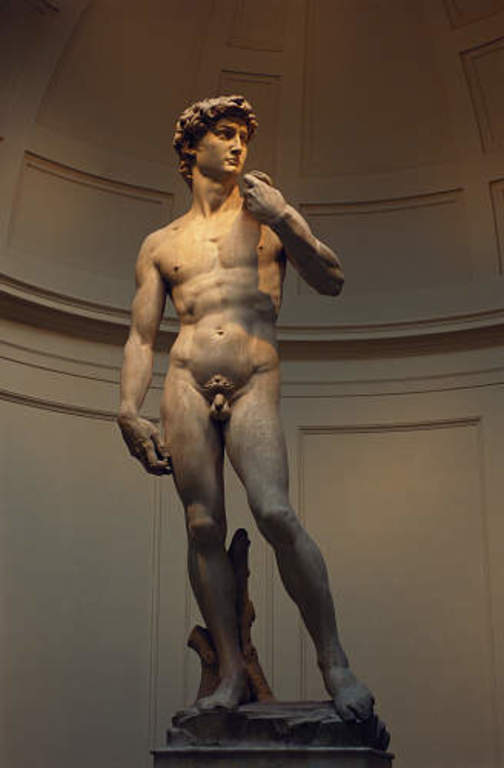

Carving is the removal of material to form an art object. Carving is a subtractive process that usually begins with a block of material, most commonly stone. Tools—usually metal or metal tipped— are used to chip away the stone until the final form emerges (Figure 4). The main concern in carving, aside from achieving the correct form, is to be careful not to chip away too much material, as it cannot be replaced once it has been removed (Figure 5). It is possible that the final shape of some carved stone sculptures result from not only the artist’s intention, but also the subtle shifts caused by unpredictable variations in the stone causing the artist to “change course” when too much stone came away. This possibility is not to suggest that trained sculptors do not know the limits of their medium: artists often encounter surprises and innovative ones can sometimes work solutions that incorporate them.

An example of the carving method can be seen in the work of Michelangelo’s Statue of David, 1501, in the High Renaissance period. The material was the very fine Carrara white or blue-grey marble that came from the Italian city of Carrara (Figure 6).

Different kinds of stone vary in hardness as well as color and appearance. Not all stone is suitable for sculpting. Marble, a form of limestone, was preferred by the ancient Greeks and Romans for its softness and even color (Figure 7). Diorite, schist (a form of slate), and Greywacke (a form of granite) were preferred by Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultures for their hardness and permanence (Figure 8). The Chinese have traditionally used jade, a hard, brittle stone found in numerous shades, most commonly green, to indicate wisdom, power, and wealth (Figure 9).

Wood is also often used as a carving material. Because of variations in grain size and texture, different species of wood have different sculptural qualities. In general, wood is prized for its flexibility and ease of forming, though it reacts to changes in humidity and lacks permanence. During the Heian era (794-1185 CE), the Japanese artist Jocho used joined wood to construct his sculpture of the Seated Buddha (Figure 10).

Video

In this video from The J. Paul Getty Museum, we can see how traditional tools were used in carving.

Carving Marble with Traditional Tools (2:47)

Relief

A relief is a work in which figures are either carved into a level plane or, more typically, the plane is removed to create images sculpted on its surface without completely disconnecting them from the plane. It is not free-standing, instead it has a background from which the main elements of the composition rise.

There are three basic forms of relief sculpture:

- bas-relief (low-relief), in which the sculpture is raised only slightly from the background surface;

- alto-relievo (high-relief), in which part of the sculpture is rendered in three dimensions; and

- intaglio (sunken-relief), in which the image is carved into the surface material.

Modeling

Modeling is an additive process in which easily shaped materials like clay or plaster are built up to create a final form. Some modeled forms begin with an armature, or rigid inner support often made of wire. An armature allows a soft or fluid material like wet clay, which would collapse under its own weight, to be built up. This method of sculpting includes most classical portrait sculpture in terra cotta, or baked clay (Figure 14). Clay lends itself to modeling and is thus a popular medium for work of this kind, although clay may also be carved and cast.

Casting

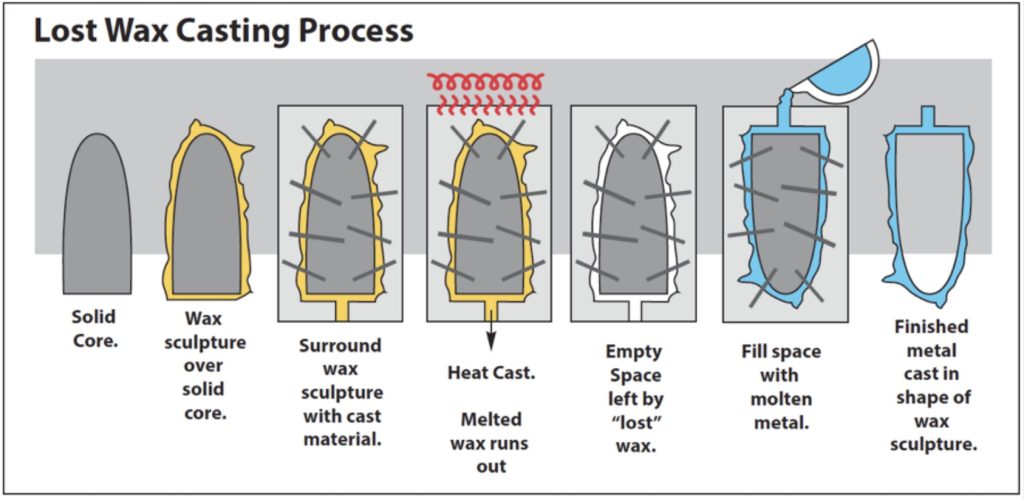

Casting is an additive method that has been in use for over five thousand years. It’s a manufacturing process by which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. One traditional method of bronze casting frequently used today is the lost wax casting process.

Casting materials are usually metals but can also be various cold-setting materials; these are materials that cure after mixing two or more components together; examples are epoxy, concrete, plaster, and clay. Casting is most often used for making complex shapes that would be otherwise difficult or expensive to make by other methods. It’s a labor-intensive process that allows for the creation of multiples from an original object (similar to the medium of printmaking), each of which is extremely durable and exactly like its predecessor. A mold is usually destroyed after the desired number of castings has been made.

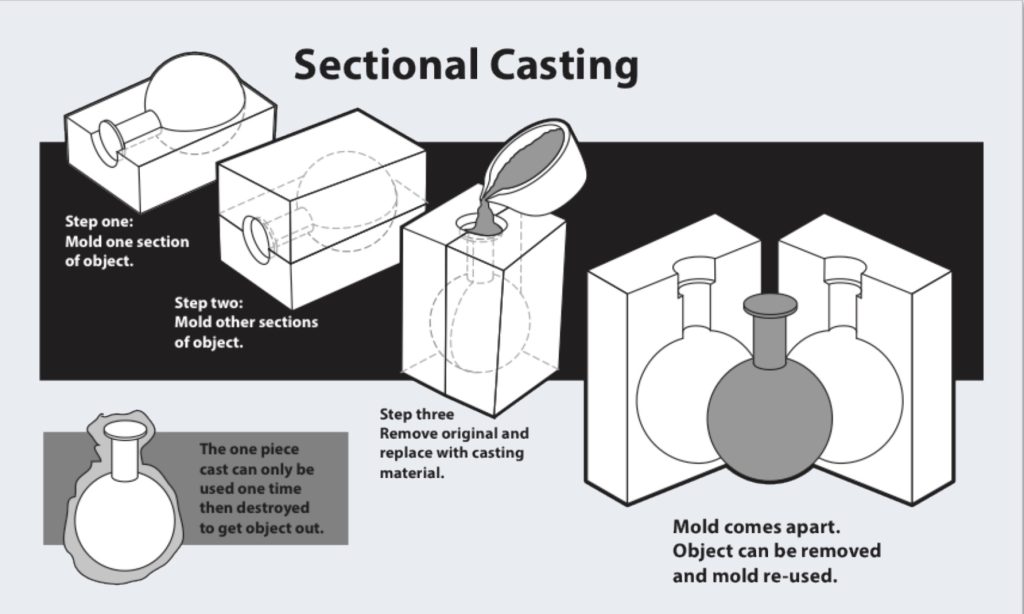

In the lost wax process, an original sculpture is modeled, often in clay, coated in wax, and then covered in plaster to create a mold. When the plaster dries, it is heated to melt the wax, which is poured out of the mold. Molten metal is then poured into the space within the mold between the (now lost) wax coating and the original sculpted form. When the metal has cooled and solidified, the plaster is broken away to reveal the cast metal object (Figure 15). In order to create multiple versions of the object, the mold must be made in such a way that it can be removed without being destroyed (Figure 16). This operation is generally achieved by separating a mold into several sections while the original is being cast. Sectional molds are also used to cast original objects that cannot be melted or otherwise removed from the mold. To cast the form, the original is removed, and the sections are then re-fastened together. In some cases, complex sculptures are cast in several pieces and the resulting metal sections are welded together.

Videos

Bronze Casting using the “Lost Wax” Technique (4:13)

The Lost Wax Casting Process (6:05)

Installation and Assembly

Assembly, or assemblage, is a fairly recent type of sculpture. Before the modern period, carving, casting, and modeling were the only accepted methods of making fine art sculpture. Recently, sculptors have enlarged their approach and turned to the process of assembly, manually attaching objects and materials together. Assemblies are often composed of mixed media, a process in which disparate objects and substances are used in order to achieve the desired effect.

Because she spent time near a cabinetry workshop, Louise Nevelson (1899-1988, Ukraine, lived USA) would retrieve wooden cut-offs and other discarded objects to use in her sculpture. Her art practice involved the use of found objects. Consider Nevelson’s Sky Cathedral (Sky Cathedral, Louise Nevelson). She filled individual wooden boxes with found objects. She then arranged these boxes into large assemblies and painted them a single color, usually black or white. Each sub-unit box in the sculpture can be read as a separate point of view or separate world. The effect of the whole is to recognize that both unity and diversity are possible in a single artwork.

Installation is related to assembly, but the intent is to transform an interior or exterior space to create an experience that surrounds and involves the viewer in an unscripted interaction with the environment. The viewer is then immersed in the art, rather than experiencing the art from a distance. For example, Carsten Höller (b. 1961, Belgium, lives Sweden) installed Test Site in the Turbine Hall, a five-story open space, at the Tate Modern in London (Figure 17). Part of a series of slides Höller created at museums worldwide, he wanted to encourage visitors to use the practical, though unconventional, means of transport, and, while doing so, to experience the momentary loss of control and whatever emotional response each individual felt.

An installation that is intended for a particular location is called a site-specific installation. Good examples of site-specific installations would be Tilted Arc by Richard Serra (b. 1939, USA), (Tilted Arc, Richard Serra); Lightning Field by Walter De Maria (1935-2013, USA), (Lightning Field, Walter de Maria); Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson (1938-1973, USA), (Figure 18); and Cadillac Ranch by the art group known as Ant Farm (Figure 19). In part because of the large scale of many of these works, installation is an increasingly popular form of public artwork.

Kinetic Art

Kinetic art is art that moves or appears to move. Generally this art is sculptural. Good examples of kinetic artworks are the suspended, freely moving mobiles of Alexander Calder (1898-1976, USA) that are meant to change shape as part of their design (Nénuphars Rouges, Alexander Calder). Homage to New York was a work of kinetic art Jean Tinguely (1925-1991, Switzerland) intended to self-destruct, although it never completed its purpose because a local fire department stepped in and stopped the process (Homage to New York, Jean Tinguely). Reuben Margolin (USA) is a contemporary artist who uses intersecting waves to create beautifully undulating sculptures. Click the following link to view a video of Margolin’s Square Wave. Beginning with simple materials like paper towel tubes, fishing swivels, and fishing line, and then moving to larger, more complex sculptures using more permanent materials like wood, metal, and wire, Margolin has made a career of creating meditatively flowing sculptures.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Common Roman Coins (Creator: Rasiel Suarez; Author: User “FSII”; Source: Wikimedia Commons; License: GFDL).

- Figure 2. Egyptian Relief Carving (Author: User “GDK”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 3. Lapith fighting a centaur (Author: User “Jastrow”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 4. A selection of woodcarving gouges, chisels, and a mallet (Author: User “Aerolin55”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 5. Sculptor Carving Stone (Author: Bain News Service; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 6. Michaelangelo’s “David” sculpture (1501-1504), housed in the Accademia Gallery in Florence, Italy (Image source: Photo by Catherine Ursillo, Britannica ImageQuest. Rights Managed).

- Figure 7. Marble statue of Eirene (the personification of peace) (Artist: Kephisodotos; Source: Met Museum; License: OASC).

- Figure 8. Naophorous Block Statue of a Governor of Sais, Psamtik (Source: Met Museum; License: OASC).

- Figure 9. Jade ornament of flowers with grape design (Author: User “Mountain”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 10. Seated Buddha (Artist: Jōchō; Author: User “Kosigrim”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 11. Intaglio, Post Classical, Lapis lazuli (Image source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 12. Mayan-Toltec culture, Bas-relief: Toltec Warrior, 1300 CE (Mexico) (Image source: Harthill Art Associates via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 13. High relief. Upper part: Madonna Enthroned with Child, with St John the Baptist and Saint Catherine; lower part: St. George Fighting the Dragon, Madonna relief mid-14th century circa 1552 (Venice, Italy) (Image source: Sarah Quill via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

- Figure 14. Bust of Maximilien Robespierre (Artist: Claude-André Deseine; Author: User “Rama”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 15. Lost Wax Casting Process (Author: Jeffrey LeMieux; Source: Original Work) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 16. Sectional Mold (Author: Jeffrey LeMieux; Source: Original Work) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 17. Test Site (Artist: Carsten Höller; Author: User “The Lud”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 18. Spiral Jetty (Artist: Robert Smithson; Author: User “Yonidebest”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 19. Cadillac Ranch, Amarillo (Artist: Ant Farm; Author: Richie Diesterheft; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

Candela Citations

- The Language of Design (Art, Design, and Visual Thinking). Authored by: Charlotte Jirousek. Provided by: Cornell University. Retrieved from: http://char.txa.cornell.edu/language/introlan.htm. License: All Rights Reserved

- Some Ideas About Composition and Design, Elements, Principles, and Visual Elements. Authored by: Marvin Bartel. Provided by: Goshen College. Retrieved from: https://www.goshen.edu/art/ed/Compose.htm#principles. License: All Rights Reserved

- Elements of Art. Provided by: The J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved from: https://www.getty.edu/education/teachers/building_lessons/formal_analysis.html. License: All Rights Reserved

- Question: What is optical blending?. Provided by: The SVGA Blog. Retrieved from: https://sgvarts.blogspot.com/2012/09/question-what-is-optical-blending.html. License: All Rights Reserved