Chapter 12.13: Islamic Art: Medieval Period (c. 900 – 1517 C.E.)

Arts of the Islamic World: the Medieval Period

For many, the Muslim world in the medieval period (900-1300) means the crusades. While this era was marked, in part, by military struggle, it is also overwhelmingly a period of peaceable exchanges of goods and ideas between West and East. Both the Christian and Islamic civilizations underwent great transformations and internal struggles during these years. In the Islamic world, dynasties fractured and began to develop distinctive styles of art. For the first time, disparate Islamic states existed at the same time. And although the Abbasid caliphate did not fully dissolve until 1258, other dynasties began to form, even before its end.

Fatimid (909 – 1171)

In the tenth century, the Fatimid dynasty emerged and posed a threat to the rule of the Abbasids. The Fatimid rulers, part of the Shi’ia faction, took their name from Fatima, Muhammad’s daughter, from whom they claimed to be descended. The Sunnis, on the other hand, had previously pledged their alliance to Mu’awiya, the founder of the Umayyad dynasty. At the height of their power, the Fatimids claimed lands from present-day Algeria to Syria. They conquered Egypt in 969 and founded the city of Cairo as their capital.

The Fatimid rulers expanded the power of the caliph and emphasized the importance of palace architecture. Mosques too were commissioned by royalty and every aspect of their decoration was of the highest caliber, from expertly-carved wooden minbars (where the spiritual leader guides prayers inside the mosque) to handcrafted metal lamps.

The wealth of the Fatimid court led to a general burgeoning of the craft trade even outside of the religious context. Centers near Cairo became well known for ceramics, glass, metal, wood, and especially for lucrative textile production. The style of ornament developed as well, and artisans began to experiment with different forms of abstracted vegetal ornament and human figures.

This period is often called the Islamic Renaissance for its booming trade in decorative objects as well as the high quality of its artwork.

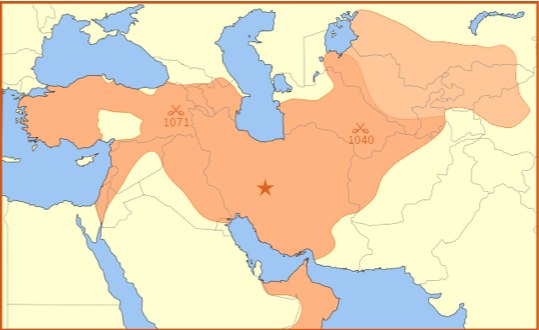

Saljuq (1040 – 1157/1081 – 1307)

The Saljuq rulers were of Central Asian Turkic origin. Once they assumed power after 1040, the Seljuqs introduced Islam to places it had not been heretofore. The Seljuqs of Rum (referring to Rome) ruled much of Anatolia, what is now Turkey (between 1040 and 1157), while the Seljuqs of present-day Iran controlled the rest of the empire (from 1081 to 1307).

The Saljuqs of Iran were great supporters of education and the arts, and they founded a number of important madrasas (schools) during their brief reign. The congregational mosques they erected began using a four-iwan plan: these incorporate four immense doorways (iwans) in the center of each wall of a courtyard.

Videos

Two Royal Figures, Saljuq Period (5:16)

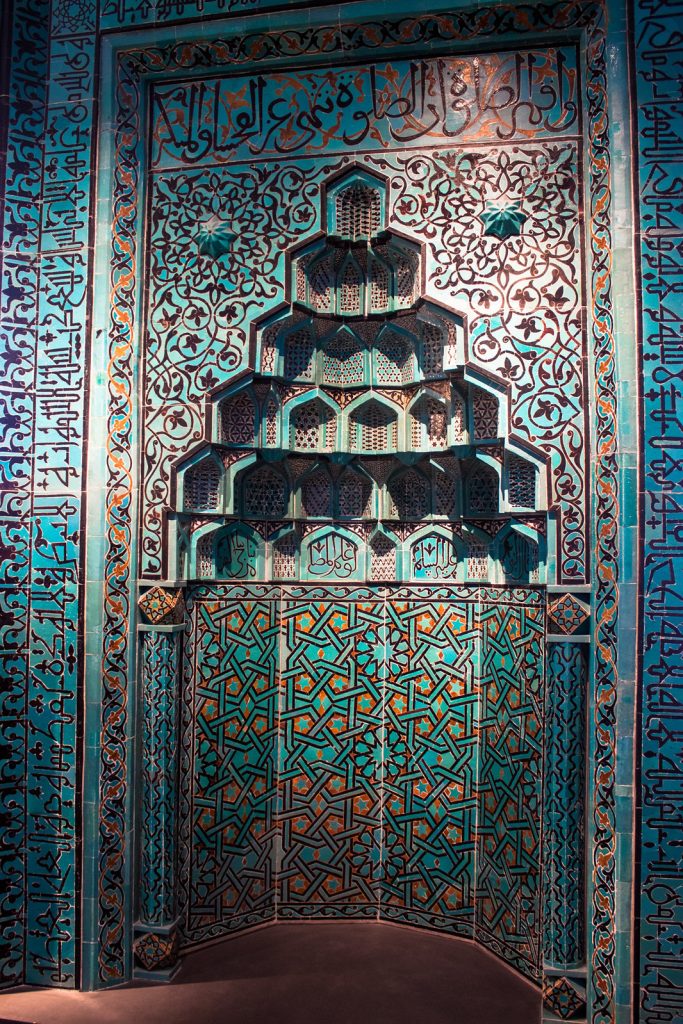

Ilkhanid Mihrab (5:41)

The art of the Anatolian Saljuqs looks quite different, perhaps explaining why it is often labeled as a distinct sultanate. The inhabitants of this newly conquered land in Anatolia included members of various religions (largely Buddhists and Shamen), other heritages, and the Byzantine and Armenian Christian traditions. Saljuq projects often drew from these existing indigenous traditions—just as had been the case with the earliest Islamic buildings. Building materials included stone, brick, and wood, and there existed a widespread representation of animals and figures (some human) that had all but disappeared from architecture elsewhere in Islamic-ruled lands. The craftsmen here made great strides in the area of woodcarving, combining the elaborate scrolling and geometric forms typical of the Arabic aesthetic with wood, a medium indigenous to Turkey (and rarer in the desert climate of the Middle East).

Mamluk (1250 – 1517)

The name ‘Mamluk,’ like many names, was given by later historians. The word itself means ‘owned’ in Arabic. It refers to the Turkic slaves who served as soldiers for the Ayyubid sultanate before revolting and rising to power. The Mamluks ruled over key lands in the Middle East, including Mecca and Medina. Their capital at Cairo became the artistic and economic center of the Islamic world at this time.

The period saw a great production of art and architecture, particularly those commissioned by the reigning sultans. Patronizing the arts and creating monumental structures was a way for leaders to display their wealth and make their power visible within the landscape of the city. The Mamluks constructed countless mosques, madrasas, and mausoleas that were lavishly furnished and decorated. Mamluk decorative objects, particularly glasswork, became renowned throughout the Mediterranean. The empire benefited from the trade of these goods economically and culturally, as Mamluk craftsmen began to incorporate elements gleaned from contact with other groups. The growing prevalence of trade with China and exposure to Chinese goods, for instance, led to the Mamluk production of blue and white ceramics, an imitation of porcelain typical of the Far East.

The Mamluk sultanate was generally prosperous, in part supported by pilgrims to Mecca and Medina as well as a flourishing textile market, but in 1517 the Mamluk sultanate was overtaken and absorbed into the growing Ottoman empire.

Later period (c. 1517–1924 C.E.)

This period is the era of the last great Islamic Empires. The Ottoman Empire, which had started as a small Turkic state in Anatolia in the early fourteenth century, emerged in the second half of the fifteenth century as a major military and political force. The Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453 and the Mamluk Empire in 1517. They dominated much of Anatolia, the Balkans, the Near East, and North Africa until the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. The Ottomans are famous for their domed architecture and pencil minarets, many of which were built by the great architect, Sinan (1539–1588) for Sultan Süleyman (r. 1520–66). This period is considered the peak of Ottoman art and culture.

The Safavids, who established Shia Islam as the dominant faith of Iran, ruled from 1501–1722 and were the greatest dynasty to emerge from Iran. Architecture, paintings, manuscripts, and carpets all flourished under the Safavids. Shah Abbas (r. 1587–1629) was the greatest patron of the arts and the Safavid Dynasty’s’ most outstanding ruler. In the eighteenth century, a period of turmoil in Persia, the Qajar dynasty (1779–1924) rose to power and established peace, and their rule saw the beginning of modernity in Iran.

The other great dynasty that oversaw a remarkable artistic and architectural output was the Mughals. Founded by Babur, the Mughals (c. 1526–1858) ruled over the largest Islamic state in the Indian subcontinent. While there had been earlier sultanates in what is today northern India and Pakistan, the emperors of the Mughal dynasty were patrons of some of the greatest works of Islamic art, such as illuminated manuscript, paintings, and architecture, including the Taj Mahal.

Images and Videos

Hagia Sophia as a Mosque (6:48)

Sinan, Süleymaniye Mosque (6:37)

Qa’a: The Damascus room (6:40)

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Court of the Lions, The Alhambra, Sabika hill, Granada, Spain, begun 1238 (Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with Permission, for education use only)

- Figure 2. The Fatimid Caliphate at its peak, c. 969 (Image source: SmartHistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 3. The Saljuq Empire in 1092 (Image source: SmartHistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 4. Mihrab (prayer niche), c. 1270, Konya, Turkey, now in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin (Image source: Glenna Barlow via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Figure 5. Mosque lamp, Syria, 13th-14th century (Image source: Brooklyn Museum) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 6. The Taj Mahal complex is a monument located in Agra in India, constructed between 1631 and 1653 CE. This is a detail view of the exterior (Image source: Biswarup Ganguly via Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 7. Exterior of Hagia Sophia. Istanbul, Turkey (Image source: Dennis Jarvis, via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 8. Suleymaniye mosque, Sinan, Turkish, ca. 1500-1588, (architect). (Istanbul, Turkey; Image source: Anita Gould, via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Figure 9. Damascus Room, dated A.H. 1119/A.D. 1707, Wood. (Damascus, Syria; Image source: Steven Zucker via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

Candela Citations

- Arts of the Islamic world: The medieval period. Authored by: Glenna Barlow. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/arts-of-the-islamic-world-the-medieval-period/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Two Royal Figures. Authored by: Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay and Dr. Steven Zucker. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/two-royal-figures-saljuq-period/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Mihrab from Isfahan (Iran). Authored by: Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay and Dr. Steven Zucker. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/mihrab-from-isfahan-iran/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Hagia Sophia as a mosque. Authored by: Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay and Dr. Steven Zucker. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/hagia-sophia-as-a-mosque-2/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Mimar Sinan, Su00fcleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul. Authored by: Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay and Dr. Steven Zucker. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/mimar-sinan-suleymaniye-mosque-istanbul/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Qau2019a (The Damascus room). Authored by: Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay and Dr. Steven Zucker. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/qaa-the-damascus-room/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike