Chapter 4.6: Funerary Spaces

Archaeologists have dated the earliest burial sites found worldwide to around 100,000 BCE, though some argue that certain ones are as old as 300,000 BCE. A considerable body of art related to funerary customs and beliefs has been found at such sites, and in many instances it is much more extensive than other types of evidence of how people lived. This disparity is likely due to the general respect given to sites of tombs and burial grounds. Usually considered sacred places, they have often been left intact when other parts of a settlement have been destroyed and rebuilt. These places, the ways they are marked, decorated, and furnished, supply us with a good deal of data to explore for insights into beliefs and practices related to burial practices and the afterlife, including how the people prepared for both during their lifetimes. Burial sites often include grave goods, such as personal possessions of the buried individual, as well as food, tools, objects of adornment, and even a variety of household goods.

The Etruscans and their culture, predecessors to the Romans on the Italian peninsula, existed from c. 800 BCE until conquered by the Romans in 264 BCE, They are well known for their highly developed burial practices and the elaborate provisions they made for the afterlife. They created a type of mound tomb known as a tumulus, made from tufa, a relatively soft mineral/rock substance that is easy to cut and carve, but hardens to become very strong (Figure 1). Like the Egyptians, the Etruscans grouped their tombs into a necropolis, but they were not reserved for the highly born.

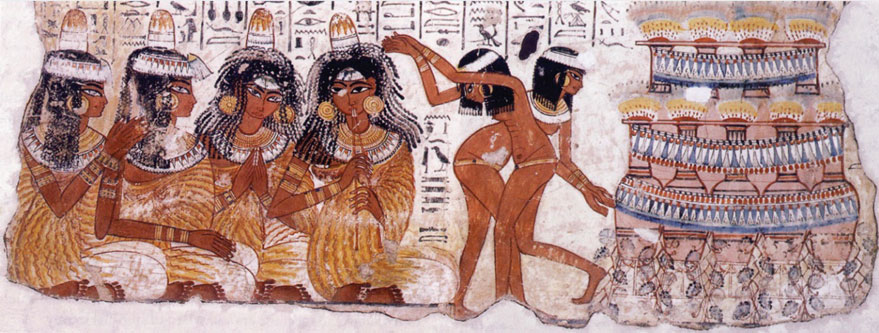

Within each tomb, the Etruscans created and decorated chambers in ways that showed what they expected would happen in a “next lifetime” (Figure 2). They expected to rejoin their family and friends and to continue many of their ordinary activities and their celebrations (Figure 3). Some tombs were supplied with a complete stock of household furnishings, while others showed scenes of athletic or leisure activities, and still others, ritual banquets. Their terra cotta sarcophagi included portraits of individuals and couples who expected to reunite and continue their married life in the afterlife (Figure 4).

In other cultures, as we have seen, the wealthy and powerful were provided with exquisitely detailed tombs and mausolea. The Samanid Mausoleum (892-943) was created in what is today Bukhara, Uzbekistan, for a Muslim amir, or prince, of the Persian Samanid dynasty (819-999) (Figure 5). Islamic religious traditions forbid the construction of a mausoleum over a burial site; this is the earliest existing departure from the tradition. The carved brickwork shows remarkably refined design and craftsmanship.

In ancient China, tombs for the important and the wealthy were very richly appointed and it is clear that the expectations for the afterlife included a need for food and other sustenance, as well as ongoing ritual appeasement of deities and evil spirits. Artisans’ remarkable skills at casting bronze were put to use for a variety of fine vessels for food and wine, altars for ritual, and various other objects (Figure 6). Also included were jade amulets, tools, and daggers. Some tombs were laid out like a household of the living, and nested coffins were decorated with mythological and philosophical motifs similar to those on the bronzes and jades. In the tomb of a woman known as Lady Dai (Xin Zhui, c. 213-163 BCE), a fine silk funerary banner carried mythological symbolism of her life and death as well as a depiction of her and her coffin (Figure 7). The expectation for musical enjoyment was exemplified in tombs that enclosed elaborate sets of tuned bells along with a carving showing how they would be arranged and played.

The Terracotta Army of Qin Shi Huang (r. 247-210 BCE), who unified China and ruled as the first Emperor of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), is another dramatic example of craft, devotion, and ritual meant to honor the dead. The figures were first uncovered in 1974 by local farmers in Shaanxi Province. The Terracotta Army is a now famous collection of more than 8,000 life-sized, fired clay sculptures of warriors in battle dress standing at attention, along with numerous other figures, pieces of equipment, and animals such as horses, around the mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, from whom China’s name originates (Figures 8 and 9). It is believed the figures were intended to protect the emperor in the afterlife.

Research has shown that the figures were created in local workshops in an assembly line fashion. Heads, arms, torsos, and legs were created separately, modified to give individual character, and assembled. The figures were then placed in rows according to rank. They were originally brightly colored and held weapons. It is believed that most of these weapons were looted shortly after the creation of the Terracotta Army.

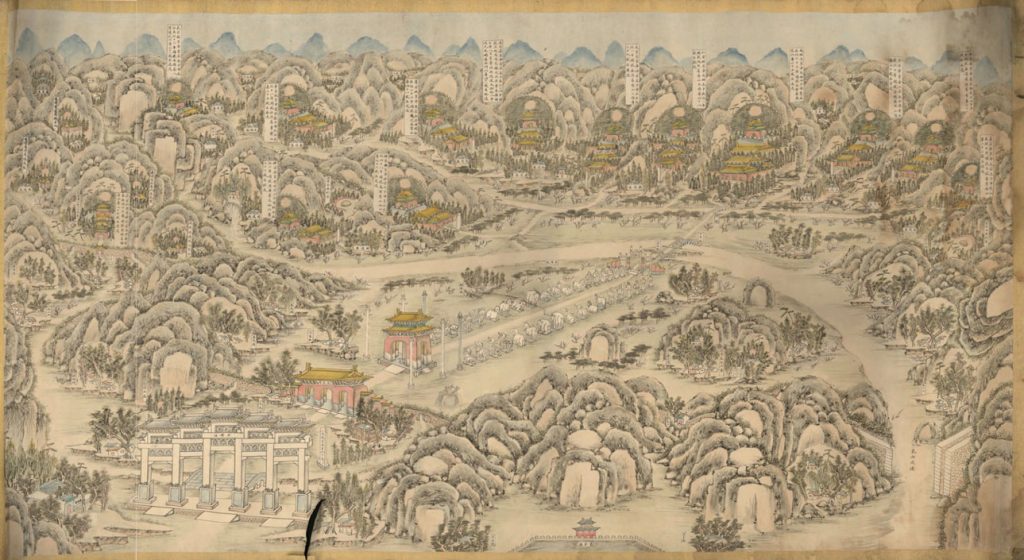

Finally, we will take a brief glimpse at a remarkable tomb complex that was developed over time near Beijing, China, for the emperors of the Ming Dynasty (1369-1644) (Figure 10). A series of thirteen tomb complexes cover more than twenty-five square miles of land on a site nestled on the north side of a mountain, where, according to Feng Shui principles of harmonizing humans with their environment, it would be best situated to ward off evil spirits. The layout includes a number of ceremonial gateways leading to “spirit paths” (Figures 11 and 12). The walkways are lined with various large sculptures of guardian animals that would also foster protection for the emperors, each of whom had a large and separate tomb complex within the precincts. Mostly unexcavated as yet, the findings so far reveal burial sites that resembled the imperial palaces in form with throne rooms, furnishings, and thousands of artifacts, including fine silks and porcelains. Again the expectation of continued power, prestige, and enjoyment of life’s pleasures is clear.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Banditaccia (Cerveteri) (Author: User “Johnbod”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 2. Tomb of the Reliefs at Banditaccia necropolis (Author: Roberto Ferrari; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 3. 5th century BC fresco of dancers and musicians, Tomb of the Leopards, Monterozzi necropolis, Tarquinia, Italy (Author: Yann Forget; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 4. Sarcophagus of the Spouses, Cerveteri, 520 BCE (Author: User “sailko”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 5. Samanid Mausoleum in Bukhara, Uzbekistan (Author: User “Apfel51”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 6. Altar Set (Source: Met Museum; License: OASC)

- Figure 7. Western Han painting on silk was found draped over the coffin in the grave of Lady Dai (Author: User “Cold Season”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 8. Terracotta Army (Author: Gveret Tered; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 9. Terracotta Soldier with his horse (Author: User “Robin Chen”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 10. Watercolor overview of the Ming Tombs (Author: User “Rosemania”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 11. Pavilion with “ways of souls” a turtle-borne stele at the tombs of the Emperors of the Ming Dynasty (Author: User “ofol”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 12. The spirit way at the Ming Tombs (Author: User “Richardelainechambers”; Source: Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Art: Design, Context, and Meaning. Authored by: Sachant, Pamela; Blood, Peggy; LeMieux, Jeffery; and Tekippe, Rita. Retrieved from: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-textbooks/3. Project: Fine Arts Open Textbooks. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike