Chapter 9.2: Byzantine Empire in 650 C.E.

In the medieval West, the Roman Empire fragmented, but in the Byzantine East, it remained a strong, centrally-focused political entity. Byzantine emperors ruled from Constantinople, which they thought of as the New Rome.

Constantinople housed Hagia Sophia, one of the world’s largest churches, and was a major center of artistic production.

The earliest Christian churches were built during this period, including the famed Hagia Sophia (below), which was built in the sixth century under Emperor Justinian. Decorations for the interior of churches, including icons and mosaics, were also made during this period.

Images and Videos

Hagia Sophia (11:04)

Theotokos mosaic, apse, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul (5:01)

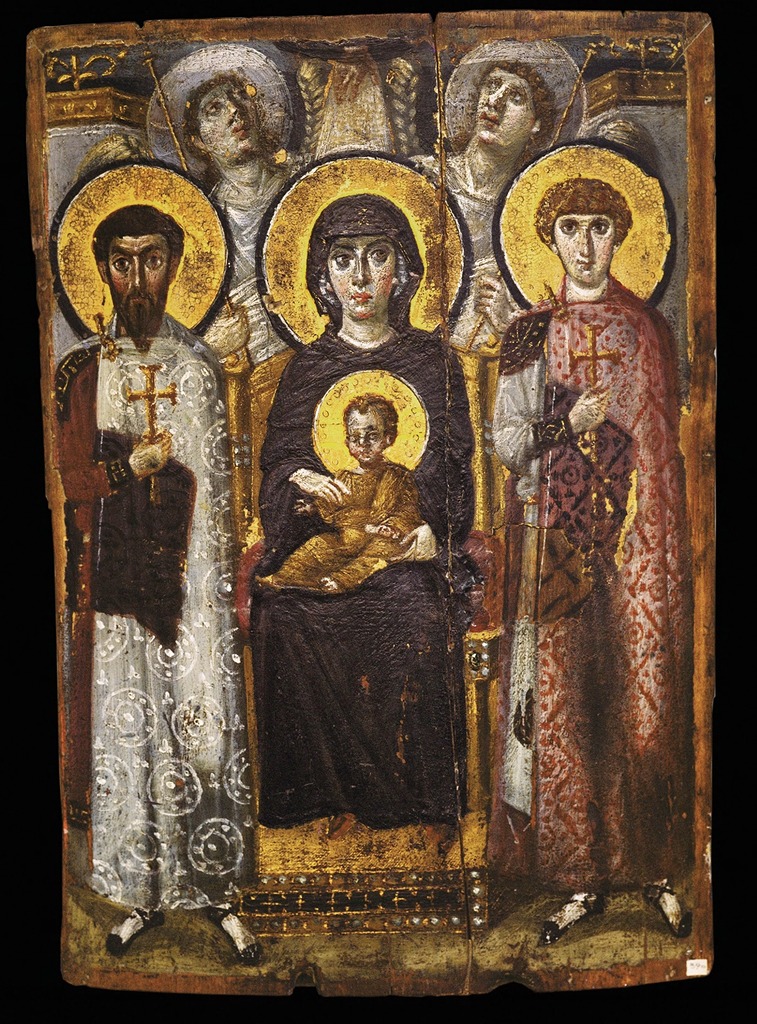

Icons, such as the Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George, served as tools for the faithful to access the spiritual world—they served as spiritual gateways. Similarly, mosaics, such as those within the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, sought to evoke the heavenly realm. In this work, ethereal figures seem to float against a gold background that is representative of no identifiable earthly space. By placing these figures in a spiritual world, the mosaics gave worshippers some access to that world as well. At the same time, there are real-world political messages affirming the power of the rulers in these mosaics. In this sense, art of the Byzantine Empire continued some of the traditions of Roman art.

The first half of this thousand-year period witnessed terrible political and economic upheaval in Western Europe, as waves of invasions by migrating peoples destabilized the Roman Empire. The Roman emperor Constantine established Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) as a new capital in the East in 330 C.E. and the Western Roman Empire broke apart soon after. In the Eastern Mediterranean, the Byzantine Empire (with Constantinople as its capital), flourished.

Christianity spread across what had been the Roman Empire—even among migrating invaders (Vandals, Visigoths, etc.). The Christian Church, headed by the Pope, emerged as the most powerful institution in Western Europe, the Orthodox Church dominated in the East.

It was during this period that Islam, one of the three great monotheistic religions, was born.

Videos

San Vitale, Ravenna (10:18)

The Problem for Early Christians

The illusionary quality of classical art posed a significant problem for early Christian theologians. When God dictated the Ten Commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai, God expressly forbade the Israelites from making any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth (Exodus 20:4). Early Christians saw themselves as the spiritual progeny of the Israelites and tried to comply with this commandment. Nevertheless, many early Christians were converted pagans who were accustomed to images in religious worship. The use of images in religious rituals was visually compelling and difficult to abandon.

Tertullian, an influential early Christian author living in the second and third centuries, wrote a treatise titled “On Idolatry,” in which he asks if artists could, in fact, be Christians. In this text, he argues that all illusionary art, or all art that seeks to look like something or someone in nature, has the potential to be worshiped as an idol.

Another influential early Christian writer, St. Augustine of Hippo, was also concerned about images, but for different reasons. In his “Soliloquies” (386-87), Augustine observes that illusionary images, like actors, are lying. An actor on a stage lies because he is playing a part, trying to convince you that he is a character in the script when, in truth, he is not. An image lies because it is not the thing it claims to be. Augustine cannot reconcile these lies with patterns of divine truth and, therefore, does not see a place for images in Christian practice.

Fortunately for art and history, not everyone agreed with Tertullian and Augustine, and the use of images persisted. Nevertheless, their style and appearance changed in order to be more compatible with theology.

Towards Abstraction (and away from illusion)

Christian art, which was initially influenced by the illusionary quality of classical art, started to move away from naturalistic representation and instead pushed toward abstraction. Artists began to abandon classical artistic conventions like shading, modeling, and perspective conventions that make the image appear more real. They no longer observed details in nature to record them in paint, bronze, marble, or mosaic.

Instead, artists favored flat representations of people, animals, and objects that only looked nominally like their subjects in real life. Artists were no longer creating the lies that Augustine warned against, as these abstracted images removed at least some of the temptations for idolatry. This new style, adopted over several generations, created a comfortable distance between the new Christian empire and its pagan past.

In Western Europe, this approach to the visual arts dominated until the imperial rule of Charlemagne (800-814.) This controversy over the legitimacy and orthodoxy of images continued and intensified in the Byzantine Empire. The issue was eventually resolved in favor of images during the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.

Illuminations

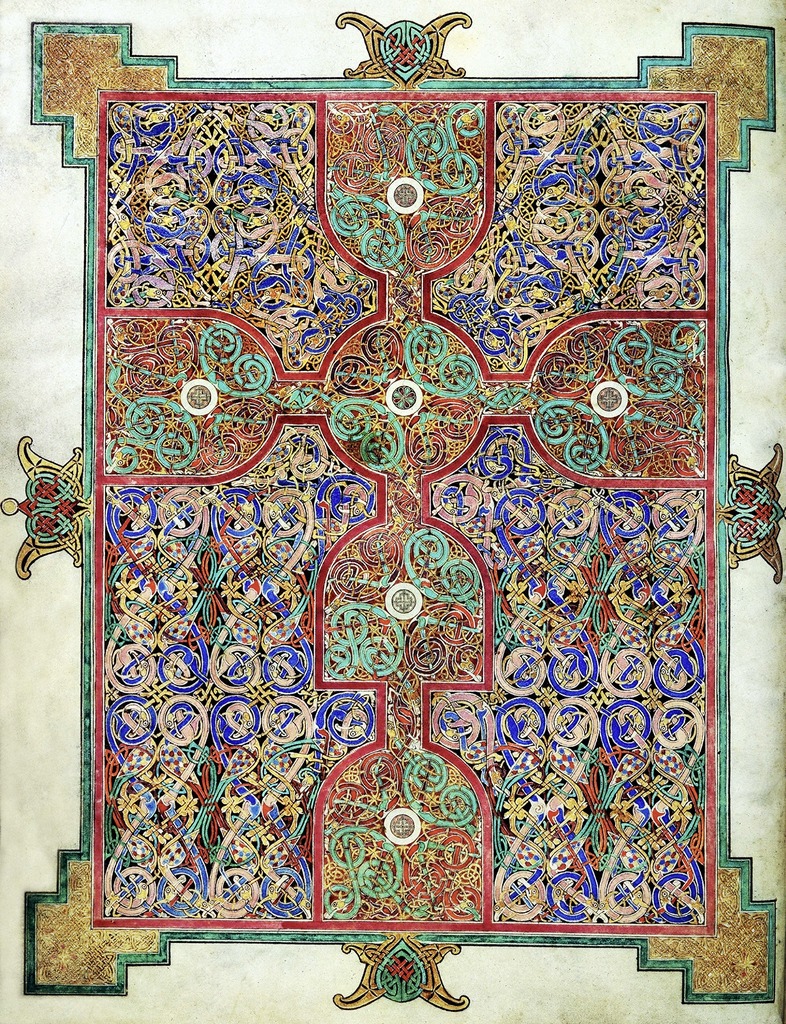

A Northumbrian monk, very likely the bishop Eadfrith, illuminated the codex in the early 8th century. Two-hundred and fifty-nine written and recorded leaves include full-page portraits of each evangelist; highly ornamental “cross-carpet” pages, each of which features a large cross set against a background of ordered and yet teeming ornamentation; and the Gospels themselves, each introduced by an historiated initial.

The Lindisfarne Gospel is a spectacular example of an Illuminated Manuscript. Monks would create these books to use in the liturgy, and to read from them during rituals.

Image and Video

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. The Byzantine Empire near its peak under the Emperor Justinian, c. 550 C.E. (Image source: SmartHistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 2. The interior of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey (Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 3. Interior, Nave, Apse, Virgin Mary and Child Jesus (Theotokos) Mosaic, Current church built 532 – 537 AD; Mosaic date to circa 867 AD, set against the original 6th-century Golden Background. (Istanbul, Turkey; Image source: Shmuel Magal, Sites and Photos via Artstor Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 4. Virgin and Child with Two Saints, second half of 6th century, encaustic on wood. (St. Catherine Monastery, Mount Sinai, Egypt; Image source: Erich Lessing/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 5. Mosaic of Emperor Justinian and his Retinue, from the apse of S Vitale, Ravenna, c. AD 546–7 (Image source: Cameraphoto Arte, Venice/Art Resource, NY via Oxford Art Online. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 6. Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy (Image source: Tango7174 via Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7. Madonna and Child (Icon of the Virgin of Tenderness), Oil on wood panel (Image source: Hulmer Collection Of Russian Religious Art, Allegheny College via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 8. Lindisfarne Gospels, Carpet Page introducing Saint Matthew’s Gospel (Matthew Cross-carpet Page), 698 (710-21), miniature on vellum. (British Library Cotton MS Nero D.IV, f.26 v; Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

Candela Citations

- Byzantine art, an introduction. Authored by: Dr. Ellen Hurst. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/a-beginners-guide-to-byzantine-art/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. Authored by: Dr. William Allen. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/hagia-sophia-istanbul/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Theotokos mosaic, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. Authored by: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/theotokos-mosaic-hagia-sophia-istanbul/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- San Vitale and the Justinian and Theodora Mosaics. Authored by: Dr. Allen Farber. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/san-vitale/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- The Lindisfarne Gospels. Authored by: Dr. Kathleen Doyle, The British Library and Louisa Woodville. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/the-lindisfarne-gospels/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike