Chapter 8.3: Egypt

Egypt’s impact on later cultures was immense. You could say that Egypt provided the building blocks for Greek and Roman culture and, through them, influenced all of the Western tradition.

Today, Egyptian imagery, concepts, and perspectives are found everywhere; you will find them in architectural forms, on money, and in our day-to-day lives. Ancient Egyptian civilization lasted for more than 3000 years and showed an incredible amount of continuity. That is more than 15 times the age of the United States, and consider how often our culture shifts; less than 10 years ago, there was no Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube.

While today we consider the Greco-Roman period to be in the distant past, it should be noted that Cleopatra VII’s reign (which ended in 30 BCE) is closer to our own time than it was to that of the construction of the pyramids of Giza. It took humans nearly 4000 years to build something–anything–taller than the Great Pyramids. Egypt’s stability is in stark contrast to the Mesopotamian kingdoms of the same period, which endured an overlapping series of cultures and upheavals with amazing regularity.

Ancient Egyptian Art

Appreciating and understanding ancient Egyptian art

Ancient Egyptian art must be viewed from the standpoint of the ancient Egyptians to understand it. The somewhat static, usually formal, strangely abstract, and often blocky nature of much Egyptian imagery has, at times, led to unfavorable comparisons with later, and much more ‘naturalistic,’ Greek or Renaissance art. However, the art of the Egyptians served a vastly different purpose than that of these later cultures.

Art not meant to be seen

While today we marvel at the glittering treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamun, the sublime reliefs in New Kingdom tombs, and the serene beauty of Old Kingdom statuary, it is imperative to remember that the majority of these works were never intended to be seen—that was simply not their purpose.

The function of Egyptian art

These images, whether statues or reliefs, were designed to benefit a divine or deceased recipient. Statuary provided a place for the recipient to manifest and receive the benefit of ritual action. Most statues show a formal frontality, meaning they are arranged straight ahead because they were designed to face the ritual being performed before them. Statuary, whether divine, royal, or elite, provided a kind of conduit for the spirit (or ka) of that being to interact with the terrestrial realm. Divine cult statues (few of which survive) were the subject of daily rituals of clothing, anointing, and perfuming with incense and were carried in processions for special festivals so that the people could “see” them (they were almost all entirely shrouded from view, but their ‘presence’ was felt).

Royal and elite statuary served as intermediaries between the people and the gods. Family chapels with the statuary of a deceased forefather could serve as a sort of ‘family temple.’ There were festivals in honor of the dead, where the family would come and eat in the chapel, offering food for the Afterlife, flowers (symbols of rebirth), and incense (the scent of which was considered divine). Preserved letters let us know that the deceased was actively petitioned for their assistance, both in this world and the next.

The Great Pyramid of Khufu

Size

The Great Pyramid, the largest of the three, was built by the pharaoh Khufu and rises to a height of 146 meters (481 feet) with a base length of more than 230 meters (750 feet) per side. The greatest difference in length among the four sides is a mere 4.4 cm (1 ¾ inches), and the base is level within 2.1 cm (less than an inch), an astonishing engineering accomplishment.

Construction: inner core stones and outer casing stones. The pyramid contains an estimated 2,300,000 blocks, some of which are upwards of 50 tons. Like the pyramids built by his predecessor Snefru and those that followed on the Giza plateau, Khufu’s pyramid is constructed of inner, rough-hewn, locally quarried core stones, which is all we see today, and angled, outer casing blocks laid in even horizontal courses with spaces filled with gypsum plaster.

The fine outer casing stones, which have long since been removed, were laid with great precision. These blocks of white Tura limestone would have given the pyramid a smooth surface and been quite bright and reflective. At the very top of the pyramid would have sat a capstone, known as a pyramidion, that may have been gilt. This dazzling point, shining in the intense sunlight, would have been visible for a great distance.

Interior

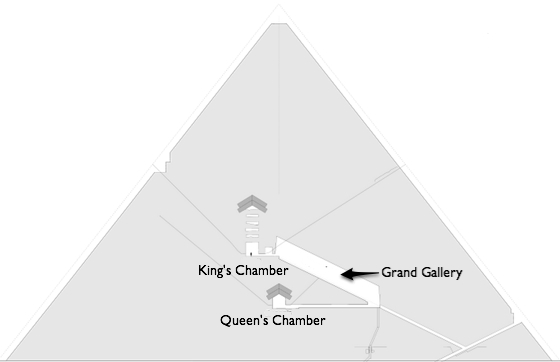

The interior chambers and passageways of Khufu’s pyramid are unique and include a number of enigmatic features. There is an unfinished subterranean chamber whose function is mysterious as well as a number of so-called ‘air shafts’ that radiate out from the upper chambers. Gallery. This corbelled passage soars to a height of 8.74 m (26 feet) and leads up to the King’s Chamber, which is constructed entirely from red granite brought from the southern quarries at Aswan.

These have recently been explored using small robots, but a series of blocking stones have obscured the passages. When entering the pyramid, one has to crawl up a cramped ascending chamber that opens suddenly into a stunning Grand Gallery. This corbelled passage soars to a height of 8.74 m (26 feet) and leads up to the King’s Chamber, which is constructed entirely from red granite brought from the southern quarries at Aswan.

Above the King’s Chamber are five stress-relieving chambers of massive granite blocks topped with immense cantilevered blocks forming a pent roof to distribute the weight of the mountain of masonry above it. The king’s sarcophagus, also carved from red granite, sits empty at the exact central axis of the pyramid. This burial chamber was sealed with a series of massive granite blocks, and the entrance to the shaft was filled with limestone in an effort to obscure the opening.

In addition to these model boat pits, however, on the south side of the pyramid, Khufu had two massive, rectangular stone-lined pits that contained completely disassembled boats. One of these has been removed and reconstructed in a special museum on the south side of the pyramid. This cedar boat measures 43.3 meters (142 feet) in length and was constructed of 1,224 separate pieces stitched together with ropes. These boats appear to have been used for the funerary procession and as ritual objects connected to the last earthly voyage of the king and were then dismantled and interred.

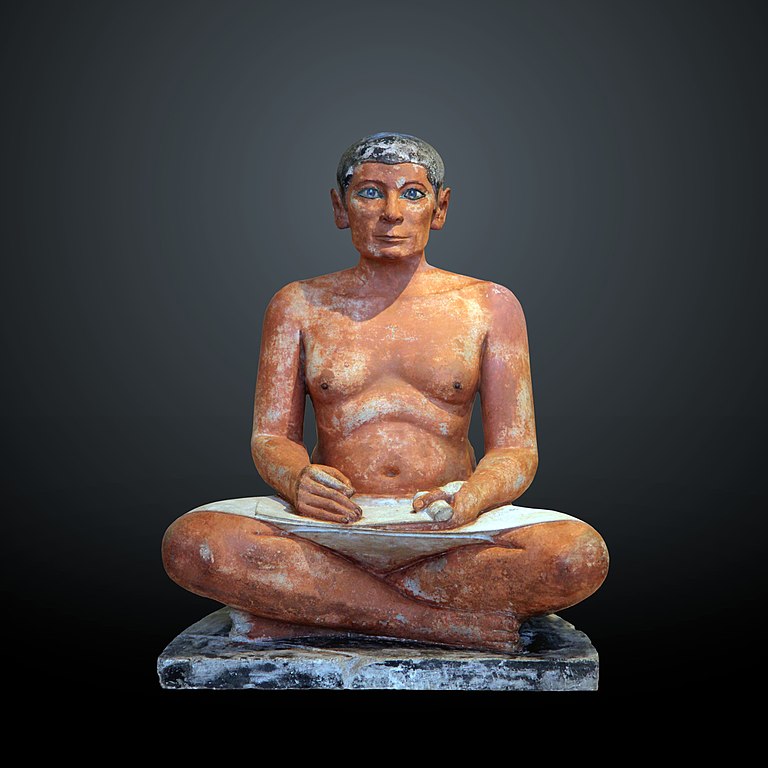

Modes of representation for three-dimensional art

Three-dimensional representations, while being quite formal, also aimed to reproduce the real world—statuary of gods, royalty, and the elite was designed to convey an idealized version of that individual. Some aspects of ‘naturalism’ were dictated by the material. Stone statuary, for example, was quite closed—with arms held close to the sides, limited positions, a strong back pillar that provided support, and with the fill spaces left between limbs. Wood and metal statuary, in contrast, was more expressive—arms could be extended and hold separate objects, spaces between the limbs were opened to create a more realistic appearance, and more positions were possible.

Stone, wood, and metal statuary of elite figures, however, all served the same functions and retained the same type of formalization and frontality.

Modes of representation for two-dimensional art

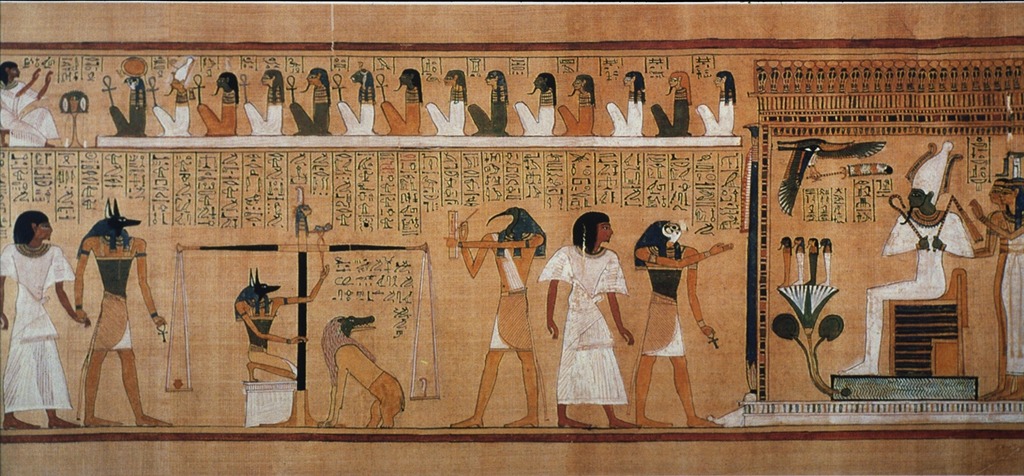

Two-dimensional art represented the world quite differently. Egyptian artists embraced the two-dimensional surface and attempted to provide the most representative aspects of each element in the scenes rather than attempting to create vistas that replicated the real world. Each object or element in a scene was rendered from its most recognizable angle, and these were then grouped together to create the whole. This is why images of people show their face, waist, and limbs in profile, but eyes and shoulders frontally. These scenes are complex composite images that provide complete information about the various elements, rather than ones designed from a single viewpoint, which would not be as comprehensive in the data they conveyed.

Hierarchy of scale

Difference in scale was the most commonly used method for conveying hierarchy—the larger the scale of the figures, the more important they were. Kings were often shown at the same scale as deities, but both are shown larger than the elite and far larger than the average Egyptian.

Videos

The Seated Scribe (3:31)

Last Judgment of Hunefer, from his tomb (7:40)

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. Beautifully preserved life-size painted limestone funerary sculptures of Prince Rahotep and his wife Nofret. Note the lifelike eyes of inlaid rock crystal (Old Kingdom) (Image source: Dr. Amy Calvert via SmartHistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 2. Painted sunk relief of the king being embraced by a goddess. Tomb of Amenherkhepshef. ca. 1187 to 1064 BCE. (Tomb QV55, Valley of the Queens, Thebes Egypt; Image source: Dr. Amy Calvert via SmartHistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 3. Pyramid of Khufu, c. 2551-2528 B.C.E. as seen from the Sphinx, Cairo, Egypt (Image source: David Stanley via Flickr) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 4. Pyramid of Khufu (Cheops), detail, courses of masonry looking up, c. 2551-2528 BCE, limestone (Giza, Egypt; Image source: Canyonlights World Art Slides and Image Bank via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only)

- Figure 5. Pyramid of Cheops (Khufu). Exterior view: entrance, ca. 2551 – ca. 2528 BCE (Giza, Egypt; Image source: Richard S. Ellis, Bryn Mawr College, via Artstor. Used with permission, for education only).

- Figure 6. Diagram of the interior of the Pyramid of Khufu (Image source: Dr. Amy Clavert via SmartHistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 7. Boat of the Pharaoh Khufu (Cheops), c. 2551-2528 BCE, cedar wood (Museum of Cheops’ Boat, Giza, Egypt; Image source Dr. Amy Clavert via SmartHistory) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 8. Statue of the Seated Scribe, c. 2620-2500 BCE, painted limestone statue, inlaid eyes: rock crystal, magnesite (magnesium carbonate), copper-arsenic alloy, nipples made of wood (Musée du Louvre; Image source: Rama via Wikimedia Commons) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 9. Psychostasis Scene (judgment of the dead before Osiris, god of the underworld) from a Book of the Dead (Hunefer Papyrus; Image source: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives, via Artstor. Used with permission, for education use only).

Candela Citations

- Ancient Egypt, an Introduction. Authored by: Dr. Amy Calvert. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/ancient-egypt-an-introduction/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Dr. Amy Calvert. Authored by: Ancient Egyptian Art. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/ancient-egyptian-art/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Pyramid of Khufu. Authored by: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/pyramid-of-khufu/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Huneferu2019s Judgement in the presence of Osiris. Authored by: The British Museum. Provided by: Smarthistory. Retrieved from: https://smarthistory.org/hunefers-judgement-in-the-presence-of-osiris/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike